Phineas Anderson

He's fought nuclear proliferation for three decades

"Nuclear weapons today present tremendous dangers, but also an historic opportunity. U.S. leadership will be required to take the world to the next stage—to a solid consensus for reversing reliance on nuclear weapons globally as a vital contribution to preventing their proliferation into potentially dangerous hands, and ultimately ending them as a threat to the world."

You may ask: What weak-minded, back-pedaling, America-hating so-and-so wrote that, and in which commie pinko rag did it appear? Turns out it appeared in that pinkest of all rags, The Wall Street Journal, and was written by former Republican Secretaries of State Henry Kissinger and George Shultz, along with former Secretary of Defense William Perry, and former Sen. (and defense hard-liner) Sam Nunn.

And you can thank Tucsonan Phineas Anderson for helping to bring the surprising views of this unlikely quartet to the public forefront.

The aforementioned four are featured in the documentary Nuclear Tipping Point, which Anderson, the former headmaster of Tucson's Green Fields Country Day School (where I am a coach), helped make. The film, introduced by Colin Powell and narrated by Michael Douglas, includes interviews with former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and others, and was viewed by President Barack Obama and members of his administration before he flew to Prague to sign the New START Treaty last spring.

At press time, the treaty was being held hostage by Arizona Sen. Jon Kyl, who wants more money for more bombs or more money for rich people ... or something.

"It's really a shame," says Anderson, who has been working passionately on nuclear-weapons reduction and security for three decades. "The New START Treaty is merely a continuation of cooperation between the United States and Russia that has been going on for many, many years."

The Trinity College- and Harvard-educated Anderson, 68, grew up in an era of nuclear-war drop drills in school and was in college during the Cuban Missile Crisis. "It just all seemed so senseless," he recalls.

Anderson's peace efforts have been of both the bridge-building and confrontational varieties. He is a master at working within political frameworks to get his point across, but he also once got an industry-mediation panel to force The Wall Street Journal to admit it had been wrong when it initially referred to a proposed nuclear freeze as "unilateral."

It was in the 1980s—when President Ronald Reagan was stirring the pot of fear and mistrust with his characterization of the Soviet Union as an "evil empire"—that Anderson jumped into the peace effort with both feet. While headmaster at Green Fields, he arranged for the first-ever student exchange with a communist country, bringing several kids from the Ukraine to Tucson and sending some Green Fields kids the other way. Some of the Ukrainian students rode alongside Tucson kids on the Green Fields wagon in the Tucson Rodeo Parade; on the wagon was a sign that asked, "Which of these kids are our enemy?"

After leaving Tucson, he took a similar position at a school in Toledo, Ohio, and became the head of that city's Rotary Club. The group would raise more than $150,000 a year for local charitable efforts, and also found the resources to help build libraries in northern Pakistan.

Now retired and back in Southern Arizona, Anderson is a world traveler who has been to more than 100 countries and finds something to like about each of them. "I love the people in Turkey and the geography of New Zealand and Nepal, but in all fairness, America is probably the most amazing place of all."

He competes in track and field in the Senior Olympics, and when I spoke to him, he had just returned from a bicycling trip at the Grand Canyon.

Phineas Anderson doesn't just want peace; he works for peace. That has to be the very definition of a hero.

Tom Danehy

tdanehy@tucsonweekly.com

Bill Bemis and Becky Freeman

These Tucson healers are fighting the devastation in Haiti

When Becky Freeman and Bill Bemis arrived in Haiti for the first time in March, they found chaos. It was just six weeks after the massive Jan. 12 earthquake. Rubble filled the streets of Port-au-Prince. Collapsed buildings were everywhere.

An estimated 230,000 people had died in the quake, according to the Haitian government. More than a million survivors were on the street, in desperate need of shelter, food and medical care.

"Haiti's problems are so big, you can be overwhelmed," Freeman says.

But she and her husband were determined to help. That's what they do in their regular lives. A certified nurse-midwife, Freeman delivers babies through El Rio Community Health Center, many of them to low-income mothers. Bemis is a clinical social worker who offers behavioral-health services, primarily at El Rio's El Pueblo clinic.

"When the earthquake happened, we said, 'Let's go,'" Freeman remembers.

They connected with Heart to Heart International, a humanitarian organization that sends medical teams around the world. In Port-au-Prince, Freeman was immediately put to work treating patients.

"We'd see 300 patients in five hours. People had headaches, itching, scabies. Their eyes hurt from the dust and rubble. They had trouble breathing because of the air pollution." Some had been operated on in the first critical days after the quake, but now, without follow-up care, they were suffering from infections.

Most of the patients were also having "intense psychiatric reactions" to their losses, Bemis says. He didn't know the local language, Creole, but Heart to Heart found him a translator and set them up in a nearby church.

"The medical people started sending people over," he says. "Almost everybody had lost one or more family members."

One traumatized man had lost his wife, a child, several grandchildren, his home and his business. A woman had run home after the quake only to find the dismembered bodies of her mother and daughter.

"They were suffering from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) and living in the street with no regular food or clean water," Bemis says.

Beginning with a handful of patients, Bemis started a therapeutic group. Each day, they would talk over their losses, and then brainstorm on ways to find food and shelter. When someone donated a sleeping bag and a tent, everyone needed it, but the members gave it to a woman who had lost her entire family. "The first person to speak up said, 'She needs it.'"

When the couple returned in November for two weeks—along with certified nurse-midwife Eileen Devlin, also of Tucson—Haiti was fighting a cholera epidemic. Devlin and Bemis had hoped to develop a women's health clinic, but cholera helped derail those plans. Instead, they immersed themselves in primary-care nursing; their biggest task was treating children desperately ill with infections.

Back at the church, Bemis was delighted to find that the pastor and his translator had kept the group going. "I got double-cheeked (kissed) by 60 Haitians," he says.

Between their two visits, the couple raised money from family and friends. Their idea of buying tents and food evolved into a plan to make microloans to small, sustainable businesses through a new nonprofit called Haiti Micro-Finance Project. Donations are coupled with the $1-per-month dues the group members have begun paying.

The money has already helped fund 10 tiny businesses. One woman used her loan to return to selling snacks to bus riders; another has resumed buying small combs and barrettes to resell on the street. Now the group is buying a small piece of land outside Port-au-Prince, with plans to eventually build housing.

Freeman and Bemis plan to return to Haiti to "keep plugging away" at their medical/mental work, but the microloans will "help people in an ongoing way," Freeman says. "With medical work, you go in, you do it, and you're gone. This is the piece we're excited about."

To donate, make checks out to Haiti Micro-Finance Project; mail to Bill Bemis, P.O. Box 64126, Tucson, AZ 85728-4126. Haiti Micro-Finance Project is a 501(c)(3) organization, and contributions are tax-deductible.

Margaret Regan

mregan@tucsonweekly.com

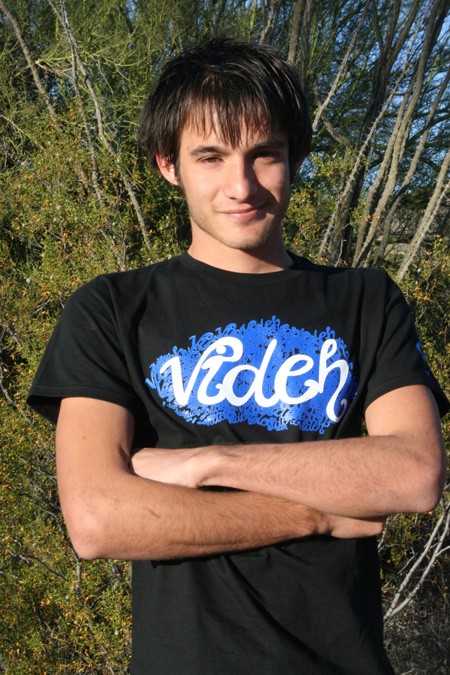

Elliott Karten

The UA student helped start a T-shirt company—and the profits go to good causes

A year ago, Elliott Karten, a philosophy senior at the University of Arizona, spent his days like a typical college student.

"I used to be pretty much like anyone else in terms of partying five days a week and just kind of not caring about anyone but myself," Karten said.

One night, he and his roommate watched a music video that altered his way of thinking. The video memorialized the deaths of hundreds of women found buried in shallow graves in the desert outside of Juarez, Mexico.

"Something about that just kind of really hit me hard. It seemed very real, for whatever reason," Karten said.

The feeling stuck with him for months after that. The idea of starting a charity-benefitting T-shirt company was thrown around by Karten and his friends, but he never really thought it was going to go anywhere.

However, within several months, Videh was born.

The company started off selling T-shirts and then donating the proceeds to whatever cause the designer chose. After meeting with lawyers and business experts, and redesigning the website over and over, Karten and co. have expanded Videh even further. When it re-launches next semester, it will essentially be a free online marketplace for nonprofit organizations or individuals to sell their wares. Videh will handle logistics, including mailing items and transferring funds.

The name itself, according to Karten, refers to ultimate knowledge or awareness within the Hindu religion. Karten fell upon the term and designed the logo himself, which resembles an infinity sign.

"It just started off with just drawings of all these different possible logos and designs for our T-shirts," Karten said. "The deeper I got into it, the more I realized that this was going to be a huge undertaking. I didn't realize how extensive it is to start up a business or a nonprofit."

Videh itself is not a nonprofit, as it covers operating expenses and then sends the profits to charities and causes. "We don't have the same public image as a nonprofit, but the more I thought about it, what I really wanted to see was corporate responsibility in the world. That's why I wanted to keep the LLC in the long run," Karten said.

Buyers can expect to browse through custom-made T-shirts; goods from Made by Survivors, an organization that provides jobs for people who have survived human-trafficking situations; and, Karten hopes, the wares of local businesses.

"This whole thing made me realize the value of how people spend their money and where their dollars go. ... There are so many issues in our world that are pretty much solvable. It wouldn't take a lot of money to solve world hunger if it was enough of a priority to people," said Karten. "The bottom line is I think people should have a choice where the money winds up instead funding some person's Lamborghini."

If you are interested in getting involved, local businesses can place their items on the website and choose whatever charity they would like the profits to go to. The easiest way for anyone to participate, Karten said, is to submit a T-shirt design and choose a charity/cause.

For more information or to donate, visit the website at videh.org.

Emily Bowen

mailbag@tucsonweekly.com

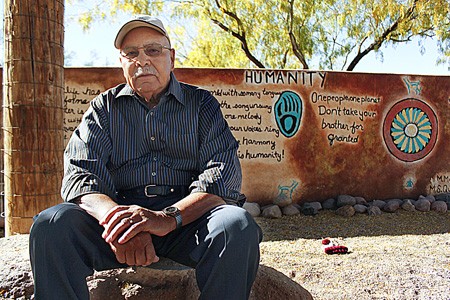

Cressworth C. Lander

The renowned public servant is now fighting to restore the Dunbar School

Born to a Buffalo Soldier and an early 20th century businesswoman, Cressworth Caleb Lander was given a name that his parents thought would mark him for success.

He has more than lived up to it.

He spent three years in the U.S. Marines in World War II, and studied at MIT, the Harvard Business School and the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. He overhauled Tucson's public-housing programs, then managed them for nearly 20 years. Presidents Carter and Clinton both called him to service in Washington, D.C. He set the national standard for engaging local governments with the Model Cities program. He served on a score of local committees and received dozens of national and local awards for community service.

Now in his 80s—and with apparently undiminished energy—he most often is found tending to, promoting, fundraising for, beaming with pride about and overseeing a new vision of the Dunbar School, the institution which he credits for much of his success.

"The older I got, the more I respected what happened at Dunbar," he says. "I had some really wonderful teachers there. They were sort of what I call '24-7.' They lived in the community, and they were your teacher at the football game and at church. In other words, they were involved in your life, and they looked out for you. And they pushed you, to do the very best that you could do."

Lander says his education at Dunbar made him competitive in every opportunity he encountered. The school yielded a host of other prominent Tucsonans as well.

"You look at the history of Tucson," Lander says. "(Educators) Laura Banks, Anna Jolivet, all of the doctors, all of the dentists, the black ministers, all were out of Dunbar, so I would say that Dunbar provided a cadre of leadership in the black community for quite a long time."

Remarkably, the years when Lander attended Dunbar were among 37 in which the school was explicitly segregated.

Tucson's schools were integrated until Arizona became a state in 1912; Paul Laurence Dunbar School, named for a popular black poet of the era, opened in 1914. In 1951, Tucson integrated its schools, and renamed Dunbar after the second teacher in Arizona Territory, John Spring.

The school was shut down in 1978 when a court declared it was still segregated. It was no longer all-black, but few, if any, whites attended. The original Dunbar School building—and a later, two-story addition—were abandoned.

A few neighborhood residents and school-district administrators advocated for the school's demolition, but they had not considered the passion of Dunbar alumni, nor did they anticipate the support that former students would offer. And they especially did not reckon on the community-development experience and connections of one Cressworth Caleb Lander.

The Dunbar Coalition formed in 1995 to purchase the property. They planned to restore the original structure to house a museum devoted to the history of Tucson's black community and to convert the newer, two-story structure into a community center with public classrooms. In 2004, with a substantial assist from Lander, the coalition won financing for the first phase of the project from the Pima County historic preservation bond fund.

Construction on phase one, which brought the original structure up to code, was completed last month. Pending funding from a bond election now scheduled for 2012, the second phase would finish the rooms to house the museum.

"One of those rooms," Lander says, "will highlight the life of the Buffalo Soldiers and their involvement in the development of the great Southwest."

Count Lander prominently among the Buffalo Soldiers' contributions.

Linda Ray

mailbag@tucsonweekly.com

Dwight Metzger

He puts the power of media in the hands of nonprofits

Tucson has a lot of amazing heroes—people and groups that reach out to the community and achieve significant positive change within it.

But there's a hero behind the heroes you may not know about.

For almost 20 years, Dwight Metzger has been helping activists and nonprofits by giving them an outlet to speak out. His independent-media center the Gloo Factory, along with in-house press projects Peace Supplies and the Feral Press, provide extremely affordable (sometimes free) printing services and workshops to any good cause that needs them. Metzger's presses—largely old-school equipment maintained and run mostly by his own (and his helpers') hands—has publicized scores of progressive projects that give Tucson the creativity, compassion, ardor and edge that make us unique.

The Gloo Factory has helped an impossibly long list of nonprofits, including No More Deaths, Save the Scenic Santa Ritas, Tucson Community Supported Agriculture, BICAS and Flam Chen. Metzger also helps individuals; for example, he recently printed books for a local woman dying of ovarian cancer whose dream was to publish a collection of stories.

Metzger's press has reached far beyond Tucson, too, through now-national activist groups like Food Not Bombs and the Guatemala Acupuncture and Medical Aid Project.

"These are (the people) I get my inspiration from and the reason I can do what I do," says Metzger. "At this point, I really see myself as a servant to these people and groups."

Metzger is an ardent activist in his own right (and not just through printing). He first entrenched himself in Tucson through political organizing with grassroots environmental group Earth First! And for more than a decade, he devoted himself to fighting the UA's construction of telescopes on Mount Graham—which includes habitat for the endangered Mount Graham red squirrel and a sacred Apache site. While that campaign didn't prevent all telescope construction, Metzger says, it did help lessen the project's negative impacts.

The Gloo Factory began with just a few printing presses that Metzger bought with a college friend (and which he still uses), but it might now be considered the backbone of Tucson independent media, "glooing" the community together and touching many people's lives without them even knowing it. If you live in Tucson and are at all progressive, you've seen a Metzger-printed publication or a Metzger-printed slogan on a sign ("Humanitarian Aid Isn't a Crime"), button ("Who's Your Farmer?"), bumper sticker ("Start Seeing Bicyclists") or T-shirt and thought: Right on!

All of these were printed with very little money, thanks to Metzger's ample dedication and serendipitous location—in a downtown warehouse space with ridiculously cheap rent. But a major setback came last year when the warehouse, owned by the Arizona Department of Transportation, was scheduled to be auctioned off to the highest bidder. When the Tucson community found out, it rallied behind Metzger, helping him raise $30,000 in six months. It was not enough for him to buy his space, but it gave the Gloo Factory a new beginning: Metzger bought a former junkyard lot in South Tucson (at 238 E. 26th St., across from El Torero restaurant), which this January will house a newly constructed Gloo Factory—better than the old one.

"I really can't thank or honor the Tucson community enough," says Metzger. "People here live and support their values in many ways. ... If we're able to show up—all of us, together, in a positive way, to make healthy change in societies—then we have a chance."

Anna Mirocha

mailbag@tucsonweekly.com

Kathleen Perkins

She helps promote and strengthen Southern Arizona's science community

Kathleen Perkins has plenty to keep her busy these days, from a consulting gig in Brussels to her efforts to make sure that kids in need at John B. Wright Elementary School get new pairs of sneakers.

But one of her chief passions remains spreading the word about Tucson's astounding science community.

Give Perkins a chance, and she'll sell you on the UA College of Science, whether she's touting the triumph of the UA Lunar and Planetary Lab's work, the cutting-edge telescopes being built at the Steward Observatory Mirror Lab, or breakthroughs in the treatment of breast cancer.

"Kathleen's understanding of the importance of branding and putting the college in front of people so that they understand the relevance of the college—she does it better than anyone else," says Joaquin Ruiz, dean of the College of Science.

She'll also fill you in on the UA's BIO5 Institute, the multidisciplinary research facility that brings together biology, food, health, medicine and technology under one roof and encourages researchers to break out of the "silos" they often find themselves in.

"It's the only institution in the world that combines the five disciplines and whose mandate is to translate science and basic research and then convert it to actionable cures," says Perkins, who chairs BIO5's Business Advisory Board. "Somebody who is maybe working on soil issues can also go look at the optics and the chemistry and not have to go to a different college or go write a different grant, because it's all under one roof. It's the future."

Or she'll tell you how the Tucson-based Research Corporation for Science Advancement is funding the young scientists of tomorrow. Or she'll set up a tour of a local plant that's building solar panels.

Back when she was a young woman hustling cocktails in Philly, Perkins never imagined she'd be spending her days talking about the scientists who make their home in Southern Arizona. It's been a wild career ride for Perkins, who left a job as a cosmetics executive in Manhattan to move to Tucson to become CEO of Breault Research Organization back in the early '90s, when Tucson was establishing itself as Optics Valley.

"I've grown to love it," she says. "I get to work with some the world's best scientists. It's an amazing thing—I get to talk to a top researcher in Alzheimer's or a top researcher in physics. And then you take it to the next level, and you have a Nobel Prize-winning scientist say, 'Can you help me?'"

She's ready to help, whether it's teaching scientists how to better explain their breakthroughs to the public, or finding ways to help science and tech companies get more invested in the community and strengthen the economy by building the jobs of tomorrow.

"You bring a scientist into a community, and chances are they're going to make $80,000 to $150,000," she says. "They're going to be highly educated and involved in their schools and involved in their children's lives. That's someone you want in your community."

She says we should also support those who are less well-off in the community, which is why she buys those sneakers for the kids at John B. Wright Elementary.

Dealing with issues of poverty, she says, is "tricky," because there are no easy answers. But she's sure that unless an investment is made in kids, society will be paying a different bill when they're older.

"Whether you have a heart and you don't want to see people struggle who are not able to pull themselves up, or you just have a sharp pencil and want the ledger to be in the black, you add up what (poverty) costs, and we all end up paying for it," says Perkins. "It doesn't have to be that way. There's enough to go around."

Jim Nintzel

jnintzel@tucsonweekly.com

Jill Rich

A helper of countless refugees, her 'wildest dream' is affordable housing for all

Jill Rich is still known as "mom" to many of the 50 Lost Boys of Sudan who came to Tucson nine years ago. Rich assisted the Sudanese refugees with housing and living expenses—but more than anything, she says, "We gave them unconditional love."

Rich started the Sudanese Promise Fund, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, in 2003 to provide a college education for each of the Lost Boys.

Prior to her involvement with the Sudanese refugees, Rich chaired the refugee-resettlement program of Jewish Family and Children's Services, mentoring resettled families from Ethiopia, Bosnia and Russia.

"I've been involved with refugees for 20 years," she says. "Some of them are like family now."

When John Thon Majok, one of the Lost Boys of Sudan, graduated from the University of Arizona in May 2005, he wanted to celebrate by slaughtering a cow at her home.

"My husband, Jim, turned sheet white," says Rich. "Plus, we're vegetarians."

Instead, they took Majok to the Pima County Fair, where he had his picture taken with a live cow and sent the photo to his relatives. The Riches purchased the cow, had it professionally slaughtered and served the meat at Majok's graduation party.

"It was a way to make his custom and our culture work," she explains.

Rich arrived in Tucson from Rockford, Ill., in 1965 to attend the University of Arizona.

"I've always believed in taking action," she says.

In 1952, when she was 5, Rich heard something about a "milk fund" on the radio. Flummoxed, she asked her parents, "'How could anyone not have milk? We always had milk in the fridge.' My parents explained what poverty was."

Her mother made her a basket, and her father purchased chocolate bars that she sold for profit in her neighborhood. She wound up donating $3.88 to the milk fund.

After graduating from the UA with a degree in psychology and sociology in 1970, Rich was accepted to law school, but decided to travel around the world for two years instead. She went into real estate 30 years ago and is currently with Long Realty.

"I'm a good juggler," says Rich. "Real estate is the kind of business (in which) I can do stuff when I don't have a client.

She volunteers for groups including Interfaith Community Services. She is co-chair of the Emergency Services Committee of Tucson Planning Council for the Homeless, which oversees Operation Deep Freeze and Project Hospitality, serving meals at 30 local congregations. Rich often eats dinner with homeless people at Temple Emanu-El, where she's chair of the Social Action Committee and vice president of the congregation.

"My preference is to work one on one with refugees and the homeless. That's where my heart is," says Rich. "My wildest dream is affordable housing for all."

Around six years ago, Rich got a call from a homeless shelter; a 19-year-old man from an African country wanted to use e-mail.

"That was unusual," she says. "He had gotten into the UA online, came here and expected to get housing at the university." Rich spoke to her husband, who agreed to "give him a chance," and the young man moved into their home.

"He did well at the UA," says Rich. "This year, I cried when he received his master's degree."

Sheila Wilensky

mailbag@tucsonweekly.com

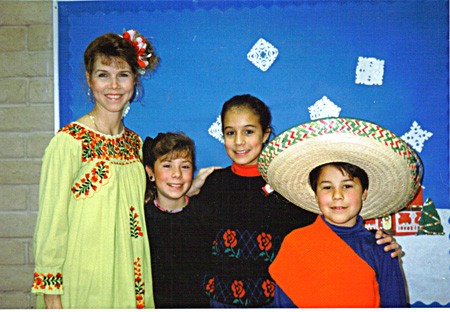

Kat Sinclair

Though she's only been in Tucson for a year, she's made her mark

During the year or so that she's been living in Tucson, Kat Sinclair has written a dissertation, served on the planning board for the Take Back the Night event at Armory Park, and worked with No More Deaths, the humanitarian aid group that works along the border.

And during the year, she's gotten pretty angry.

"I'm the kind of person that no matter where I go, I have to get involved with something," said Sinclair.

She said she learned about No More Deaths when the group gave a presentation at her church. "What I understood when I started meeting with them was just the shock," she said. "(I thought), 'What do you mean immigration (officials) don't actually have detention standards? What do you mean when they deport families, they specifically separate men and women, and husbands and wives?'"

When she first moved to Tucson, being from the East Coast, she didn't know anything about the border. "I got here and was morally sickened by the way that people's civil rights were being treated in this state. ... I started learning a lot, and listening, and reading a lot of books about the border," she said.

Sinclair then began doing what she could. Much of her work revolved around SB 1070. She set up protection and support networks for illegal immigrants—informing them of the rights they had, getting them attorneys and helping them fill out paperwork.

Sinclair's particular role was as the tech person; she has set up a large Internet database that helps connect supporters in different cities, who can in turn check on immigrants' relatives, houses and belongings.

The database Sinclair worked on is essential. Sinclair said that when people are deported, they are often sent with only the possessions they have on them—sometimes, only their clothing. The database can be used to get things like wallets and money back to the migrants.

Sinclair said No More Deaths is currently working to help a woman who was brought to the United States at age 7. She has two children who are U.S. citizens.

"They just did a raid on her work, and they're going to deport her. ... There's not automatic dual-citizenship, so she can't take her kids with her. Beyond that, she knows nobody in Mexico. When I was 7, I lived in Maine. I don't remember Maine, except that it was cold!"

For more information on No More Deaths, call 495-5583, or visit nomoredeaths.org.

A. Greene

mailbag@tucsonweekly.com

Charlotte Speers

Instead of retiring, she dedicated herself full-time to helping the homeless

When Charlotte Speers steps outside of the tiny Casa Maria soup kitchen, she's greeted by dozens of men, bundled up in jackets and hooded sweatshirts.

"Hello, Miss Charlotte," someone says to the right. "Hola, señora," someone says to the left. Speers smiles back and waves to others; she greets most of the people using their first names.

To a person who is unfamiliar with this scene at 401 E. 26th St., it could seem chaotic: a crowd of homeless or near-homeless and hungry people milling around the small Catholic Worker soup kitchen supervised by a Virgen de Guadalupe mural on the wall.

"I think of this as the real world," Speers says. "Everything else on the eastside of town is nice, but to me, this has always been the real thing. It's a reality check."

The eastside Speers talks about is a part of Tucson she gave up about two years ago, when she sold her house and rented one across the street from Casa Maria. Speers' husband passed away seven years ago; she was done raising eight children and fostering more than 80 kids over the years, so the timing was right. Casa Maria had been part of her family's life as a longtime volunteer, and when Brian Flagg, Casa Maria's director, asked her to come onboard full-time, everything fell into place.

Speers says her Catholic religion and the Catholic Worker Movement—started by Dorothy Day during the Great Depression—motivates her to do this work full-time rather than formally retire. While some describe feeding, clothing and housing people as charity, Speers calls it justice.

Speers' days start at 4:30 a.m., when she leaves her modest brick home and walks across the street to open the soup kitchen and get the coffee going. Around 6 a.m., the first crew of volunteers arrives to drive a truck to local supermarkets to pick up food donations; others begin prepping lunch bags, each containing a couple of sandwiches, a hard-boiled egg, some fruit and crackers or chips.

"A hero?" Speers asks uncomfortably when queried about being included in this issue. "If anything, the other volunteers are heroes. They have amazing stories, and we couldn't do this work without them."

In the front room of the soup kitchen, volunteers prep soup in two industrial-size pots that will be served for lunch. Almost 600 sack lunches are prepared and passed out every day, along with more than 200 family food bags. A shower is also available, and at a building across the street, people can get clothes and toiletries. Casa Maria also offers medical and legal assistance, as well as citizenship classes in Spanish. Everything comes from private donations.

Outside, Speers greets a group of people from a Methodist church who volunteer once a month. She helps them bring in clothing donations and compliments the handy work of other volunteers who've organized the clothes.

"Now if I can just get some volunteers to come in once a week to keep this up. I could really use that right now," Speers says.

A man pops his head in: "Miss Charlotte, do you have any razors?" She asks him to come back in an hour and turns to work with two men who've arrived for help; one just got out of prison.

Speers says some newly released prisoners arrive only in a T-shirt and shorts. If they don't have a belt, the prison gives them a plastic trash bag to hold up their pants.

"Sometimes, we're the only place some people will come to," Speers says. "These are hard times. We are so busy. Today, I guess I looked sad, but I was just focused. One of the guys said to me in broken English, 'Don't be sad. Money doesn't matter. What matters is the love in your heart and faith in God.'"

Speers smiles and nods her head in agreement.

For more information on Casa Maria, call 624-0312, or visit www.casamariatucson.org.

Mari Herreras

mherreras@tucsonweekly.com

Terri Valenzuela

The late single mother unselfishly battled pain and poverty to serve the Community Food Bank

Terri Valenzuela left a lasting legacy of community service behind when she passed away in February at the age of 55. Her family and supporters of the Community Food Bank hope to continue that work through an endowment fund set up in her name.

As a young woman, Valenzuela was a kindergarten teacher and, later, a flight attendant. In the early 1980s, she was struck with both rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, which left her unable to work. Despite that, she raised three children as a single mother.

"She never made us feel we were going without," recalls her son, Andres. "She always made things work."

To accomplish that, Andres says, his mother sacrificed. "She went without a lot," he recalls, "but we had money for school events."

For support, Valenzuela turned to her church, St. Andrew's Presbyterian, and to the Community Food Bank. Her involvement there eventually led to her joining the Food Bank's board of directors.

"My mother didn't have money to contribute," Andres points out, "but she did have time. She brought the perspective of a food-box recipient to the board. She was the first person on the board with that view and could show what it was like to be on the other end (of receiving assistance)."

Charles "Punch" Woods was the Food Bank's executive director when Valenzuela joined the board.

"She became a good voice for the Food Bank as a consumer and user (of its resources)," Woods says. "She was candid and honest. She also wasn't afraid to speak up at the board meetings. She gave back to the Food Bank every penny she could in terms of time and effort."

However, her service was often a hardship on Valenzuela, Woods says. Because of her deteriorating physical condition late in life, she had to get out of bed around 3:30 a.m. to make the 7 a.m. board meetings.

"Terri was a saint, and I loved her dearly," Woods says.

Andres remembers that his mother was unselfish and always wanted to help others.

"She struggled with pain, but always made it to Food Bank events, because she knew how important it was," he says. "Growing up, we'd watch her suffering, but she'd still get up every morning."

To continue his mother's history of service, Andres recently joined the Food Bank board. As a nutritionist at St. Mary's Hospital with both bachelor's and master's degrees from the UA, he's proud to follow in his mother's footsteps. "I saw what her involvement meant to my mother—the ability to help people and give back to the community."

An endowment fund has been established at the Food Bank in the name of Terri Valenzuela. It was started with generous donations from her children and family friends, and Andres says the goal is to keep his mother's efforts going.

"We discussed it before she passed away," he says of the fund. "It will continue on what my mom had started."

Contributions to the Terri Valenzuela Endowment Fund can be made online at www.communityfoodbank.org, or by sending a check to the Food Bank, with the endowment fund noted on the memo line, to Community Food Bank, P.O. Box 26727, Tucson, AZ 85726-6727.

Dave Devine

ddevine@tucsonweekly.com