Sometimes it's impossible to hide the inner turmoil, so scars show up on the outside. Junior's run long, thick and wide, snake along his arms and chest and hands. I'd guess some kid street-survivor of multiple machete fights but these are self-inflicted. Much thinner wounds, as if carved with razor-blades, angle up from the corners of his mouth into a forever grin, Joker-style, and his countenance is calm like Mos Def. His élan is raver: rose neck tats peek up from under a leopard-print kerchief, colorful mismatched socks and magenta shorts and facial dot piercings; nipple rings dangle, jingle in the hot breeze. Junior is 23 years old, been without home eight years and he is the opposite of unsure and frightened, and ideas form that I cannot shake.

Junior is guarded and his voice is disarmingly soft and it floats on complete sentences that say only what he wants to say. He grew up on Tucson's south side. He was no enthusiast of his father. "He was sexually abusing my sister," he tells me. "And my mother always tried to compare me to him, always calling me Junior." But he will check in with his mother. "My mom works for a housekeeping and maintenance company. I get toilet paper and things from her and give it away to other people out here."

Junior almost finished high school but didn't, and he was already homeless. "My thought processes are different than most," he explains.

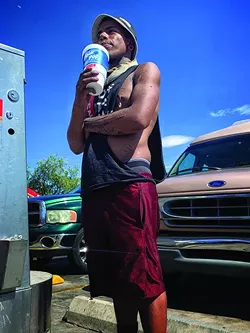

I take him inside Circle K for Polar Pops and Newport smokes. He gets carded for the cigarettes even though I am buying and the woman behind the counter will not budge. He has no ID of course so we get smokes at the smoke shop next door.

A smoke and a Polar Pop are riches to Junior and Adam Perez, aka Chief, a dude waiting for us in the shade at the side of the K in the shimmering heat. He is called Chief because he is part Native American and also because he is known to sometimes help other homeless people out here. Half of Chief's 32 years have been spent living on the streets and he still looks young but only in that tragic Heath Ledger way of living on borrowed time. There is a kind of Native pride about him, a sense of earned fearlessness to fight a non-stop supply of man-made misery, and his back is always straight and he makes direct eye contact. He is lithesome and tireless with great punk-rock hair and his street-star affect of EDM and rock 'n' roll is something. He explains to me the significance of his ankle bracelets and the semi-truck tattoo on his shirtless torso but the details get cloudy. His vocal and body languages are street-honed and sometimes difficult to decipher, either sad and messy or speedy. But he is like some manic street preacher and his run-on sermons reference God often but what becomes clear is he will help others who need it and says he forgoes grudges against those who fucked him over.

Chief is thin enough he can slip into parking lot charity clothing bins and gift his winnings to other homeless. He fabricates his wearables from such, and the handy work is detailed, aesthetic and thoughtful.

"These people out here," he says, "I care about because no one cared about me. There are times when I protected a woman out here from getting raped. Been put in life or death situations for that woman."

He adds, "Trust me, there are people out here not made by God."

When things get bad Chief sells his body to men (and sometimes women) for cash and he says it is nothing to be proud of. And Chief and Junior are hardly lovers, but Chief nods at Junior, "I want him to be but he doesn't want to," he says. Neither speak for, nor interrupt, the other, and there's a kind of universal indifference about them that says: this is how we roll and the world ignores us and we accept it. And there is nothing that can shock us.

These guys: Their stuff is crammed inside a shopping cart, topped with the blue bike frame Perez liberated today from a lucrative trash pile. They have no home, not even a campsite. "Cops find out where we are camping and destroy the campsites every time," Chief says. "Sometimes I don't sleep because if I go to a park bench I can get robbed, beaten and murdered."

Action and hustle swirls outside this Circle K, in the dirt and heat shade, the street-hassle gaits and homemade bikes, the young busted humanity with nowhere to go and rushing to get there. Black and Asian and white and brown, and Junior and Chief know them, gift them smokes or toilet paper or clothes or whatever. An entire community unfolds at Circle K at Stone and Ft. Lowell, in winks and nods and whispered words and quick car trips.

Junior and Chief have nowhere to be but they do have somewhere to go in this moment and I'm not exactly invited. Neither Chief nor Junior own a working phone so I give them my number with a firm request to call. They promise to call the following day. I watch this ragtag duo push that rattle-trap cart out into the 110-degree sun, around the corner of Circle K, beyond the head shop and into the unknown, yet wholly desegregated community of Stone Avenue. A couple of arrested souls up against walls. I wait for them to call and the call never comes. I drive around and never see them.

A few days earlier I am inside a chain-linked fenced lot near that Circle K, which houses both an auto repair place and a graveyard for broken or dead cars, trucks and RVs, at least one of which is inhabited by at least one homeless person.

I meet Justin, the guy who mans the auto repair side of this yard. Those who roll in and out with their busted cars say he can repair anything on wheels. They say he takes in kids from the hood and teaches them auto repair. I want to learn more about him because he is obviously kindhearted and cool and he tells me he grew up in Tucson.

But there is the complication of a sharply dressed Chicano with perfect braids who is chilly on a blazing day. One wrong word and he might push my head in. He does not trust me, a white rock 'n' roll leftover with long hair armed with a pad and pen, and he gets in the way. I get that he doesn't trust me. I would not trust me.

At first this Chicano seems like a good dude and we talk about his art and how he has been drawing since he was a kid, and how the children's book he created in prison is filled with riddles and rhymes, and now he is writing songs and into exploring differences in humanity, the differences "of wanting something and needing something," and though he says he grew up saddled with a learning disability he's anything but slow. He doesn't give his name or phone number, much less permission for me to snap his photo because giving all that stuff up is taboo from where he is from. That is cool, I tell him.

Later he gets angry because I am posing questions to others here who do not seem to mind me asking them questions and he begins to glare at me and hover. But Justin is busy, wrapped up in auto repairs today and so I tell the Chicano I'll return the next day to see his art and talk about what the hell he is all about. I tell him I'll bring him books I wrote so he can see I am not totally full of shit. He seems okay with the plan.

I return the following day to talk with the Hispanic gentleman and Justin but they are nowhere to be found and so I'm talking to Tia, who is staying on and off in a RV in the corner of the dirt lot. The RV is ramshackle and up on blocks with no motor. It's got to be 115 degrees inside of that thing. (Tia cameoed in a previous Tucson Salvage column and she is too pretty and white and healthy-looking to be anywhere near a homeless camp. You don't see homeless people like her every day.)

"People hate me because I am a hooker," she says.

Tia is young (30ish) with a disposition leaning toward the genial, and speedy but time is probably still on her side. She's thin and thinner still with smooth skin and sharp nose, and a wide, big-tooth grin recalls young Faye Dunaway and today her blonde mane is pulled back. She wears flowered shorts and a pink top, and is using jugged water to rinse out a black cotton blouse that she hangs on a Palo Verde tree to dry.

She talks about meth and her worlds and how she arrived from Sierra Vista via Pittsburg and Madison, Wisconsin. She talks with affection toward her "hobo dad" who had her back after she arrived in Tucson three years ago. "I would walk down the wash at two in the morning in super-tight mini-skirts and he'd say, 'Are you crazy? You'll get raped out here.'"

She is open and I ask her if she has ever been raped. "Do you mean on the streets or in my personal life?" She nods and shrugs, as if to say, man, that is but half of it. Her meaning is unmistakable and in that second it weighs heavier than usual in my thick head how much harder it is to exist in this very world for a homeless woman than it is for a homeless man. Tia talks about how her biological dad died young and how she got kicked out at 14 because mom had a new husband and a new life and Tia didn't fit in with that new life, and how she finished high school and began college while living on couches. About how the MDMA was her downfall and how meth is everywhere in Tucson ("It's so crazy, you can't even get it back East"), and how she is living mostly here on the streets, and man is she resigned and jaded. "I'm part of it now," she tells me. "I was trying to change."

We talk heroin and how she hates it because, for one thing, it killed off all of her friends back home. "It was that thing where we would graduate high school and take a year off before college but everybody would die from heroin."

Tia is storing things here in this RV, her bicycle is locked up to the chainlink fence, and she has nowhere to go right now.

Charles Thigpen is helping her out. The Florida-born, Texas-raised 38-year-old calls himself a good old southern country boy and that seems like as fine a descriptor as any. He talks of his love for his mother "who stood by him" through troubled times, and whom he hopes to rescue from a sad assisted-living facility in Florida. He has soft pinned eyes and leathery skin and looks like the kind of dude who could fix damn near anything. He wears one of those arched bull-hide cowboy hats Ronnie Van Zandt popularized years ago and handsome metal bracelets he Dumpster-dived, and he takes care of himself the best he can so as not to "look like I'm homeless." Compact and powerful like any man familiar with hard work in the sun.

He has been an auto mechanic since he was 11 years old but now it is "just a hobby" because his interest waned as computerized cars took over but he occasionally helps Justin out here. (This auto-illiterate digit is damn impressed watching him install a motor into a car). He is a landscaper by trade whose own landscaping concern has yet to take off so now he is a groundskeeper here on this compound and seems to do a pretty remarkable job as the place shows real organization amidst such junkyard chaos, the brave lizards, rusted propane tanks and dusty oleander. He keeps a hidden campsite near I-10 and Grant Road.

Now Charles he has seen some things, the busted homes and death and jail and drugs and streets. His twin brother died on him several years back and you can imagine how that rattled him to his bone marrow. He tells me how he got arrested and did a year when he was 22 for having sex with a 16-year-old girl. Consensual and she lied about her age, he says, and someone called the cops and that was that. Sure enough, Charles's mug is easily found on the Arizona Department of Public Safety database as a sex offender and he has been busted several times since the incident because he is homeless and can show no verifiable address, a necessity for such human violations. Even though Elvis and Iggy and Bowie and Jerry Lee and Marvin Gaye and all sorts of folks have famously bedded underage women, it is a wretched thing to me and maybe I am an asshole but I can't have much sympathy for Charles no matter how contrite or ashamed he may seem to be.

There is still the complication of the Chicano. He could pound my head, and Charles says, "he doesn't trust people. How he is. You can call me if you want to talk more. ..."

The Chicano steps around the RV in a cloud of menace carrying a mostly finished bottle of Johnnie Walker Red and his eyes are as red as the label and in my experience as both a drunk and recipient of ugly drunk behavior the red eyes are never a good sign, and why did I forget the books? I tell him I don't know why I forgot the books but I will dial up the internet on my phone to show him I'm not so full of shit, and that's when he about takes me down. His frightened mean red eyes. ■

Brian Smith's collection of essays and stories, Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections of La Frontera, based on this column, is available now on Eyewear Press UK. Buy the collection in Tucson at Antigone Books, 411 N. Fourth Ave.