Presiding in the Louvre at the top of a dramatic staircase, Winged Victory is an extraordinary marble goddess, 23 centuries old. She lost her arms and head centuries ago, but she's still triumphant. Bold and strong, her wings outstretched, her garment whipping in the wind, this Greek goddess of victory embodies female strength.

Strange as it might seem, I couldn't help but think of Winged Victory on a recent visit to Davis Dominguez.

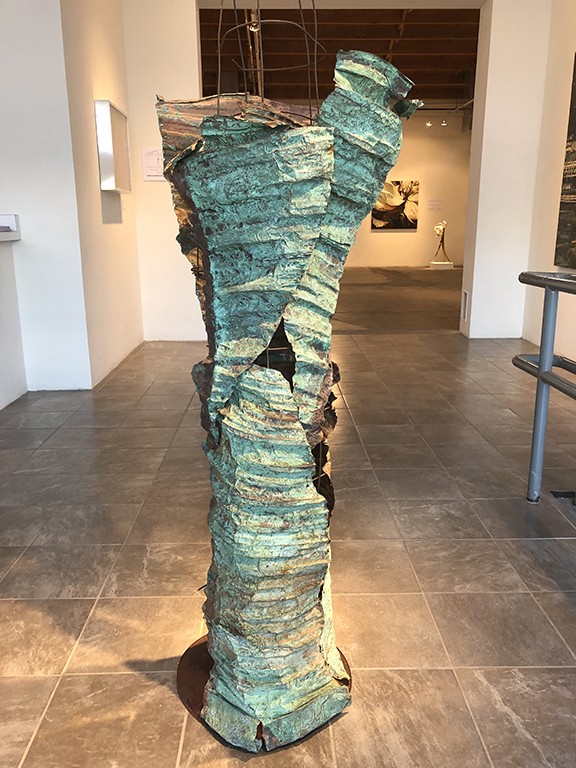

Right at the front of the gallery is an exhilarating sculpture by Tucson's Barbara Jo. A curving female-esque figure 6 feet tall, "Whirl" is wrapped in a stretch of green copper that defiantly swings outward, just as Victory's wings do. The found metal it's made of is as tough as the goddess's marble. And like Victory, the gutsy "Whirl" exudes female power.

The big, self-confident figure makes a fitting entrance to FOUR, a show of work by four women at the height of their careers. Their artworks are wildly different from each other, but most of the pieces decry environmental troubles, either pointedly or subtly.

Barbara Jo, a longtime art teacher at Pima College, now retired, has made an assortment of 3-D works, nearly all of them crafted from found objects. Instead of buying expensive traditional art materials—like marble, just for instance—she salvages discarded materials: unwanted old bedsprings, baskets, wire, wooden staves from antique barrels, even pieces of old pianos.

Her playful works, made from trash, gently make a point about the virtue of re-use in a consumption-driven world.

A dead piano gets new life in "Double Play." The piano's keys have been plucked from the instrument and hung vertically in a handsome array propped up on steel poles. The long keys, white and black at one end and a rich red brown at the other, are arranged rhythmically—some keys soaring high, others dipping low, as though they were still making music.

"Dimensional Drawing" looks like a sketch dancing through the air. A floor work on three legs, it's like a human figure whose head is one big scribble of curling wire, bedsprings and straw. Colored white and tan and dark brown, these materials in jump and loop around each other.

Hanging from the gallery's high ceiling, 14 plywood carvings sway like tiny wooden lamps in "Plumb Installation." Barbara Jo has carefully carved lowly plywood into a thing of beauty, colored a handsome pale tan. The pieces look like spinning tops or lamps—or maybe, in a stretch, like Grecian urns.

Patricia Carr Morgan made a splash early this year in the show Blue Tears at the Tucson Museum of Art, with photo images of Antarctica and Greenland so huge that they dangled from the rafters. At Davis Dominguez, in smaller-scale altered digital photos, the artist continues to investigate the world's endangered frozen lands.

Climate change has delivered a blow to these cold places: higher temperatures melt the ice and the melted water raises sea levels. Polar bears in Greenland are losing their sea ice habitats; likewise, in Antartica, Emperor penguins are losing the ice shelves where they breed.

Tellingly, Carr Morgan calls this body of work "Expiring." Mostly she focuses on the natural beauty of these regions, documenting what one day may disappear. "Greenland 2015-2019, Expiring #1" is a beautifully colored vertical of brilliant orange and yellow lights bursting over a deep blue landscape. "Antarctica 2008-2019" is all wintry blues and whites, tracing the mountainous outlines of this land of ice and snow.

Susan Conaway's bold paintings revel in the juniper tree, native to the parched desert Southwest, a region officially in drought for years. Her works are not pretty: they're strong. Strong. Her dead tree trunks are hyper-blown-up, so enlarged that they border on abstraction. Zeroing in on the deep, harsh crevices in their dried-up bark, Conaway gives them a whiff of danger.

"Careful of Trespassing" pictures a slice of sharp-edged bark, painted gray, brown and black. The image takes up the entire canvas: there's no escape from the trunk's splintery menace. "Lie in the Bushes and Wait" seems to have been murdered: a deep knife cut crosses its bark. Even in some flower paintings, nature seems to be lying in wait, ready to ward off human threats.

The gifted landscape painter Debra Salopek, whose last suite of paintings made the Nebraska flatlands radiant, has here turned her attention to the beauties of New Mexico.

"Dusk #1" is perfection, with the classic three-part western view: big sky above, long stretch of grassland below, and rolling mountains hugging the horizon in the middle. The colors are muted, gray blue for the darkening sky and even darker mountains, and subdued earth green in the foreground lit by the last sun rays of the day.

Salopek moves back and forth from oils on canvas to dark drawings on paper. Gorgeous as her works are, there is an air of sadness in this suite, a melancholy about a West that's changing. These wide-open spaces she paints are parched and fragile, and too many of them are threatened by water-gulping development.