If President Biden had set out to make the Arizona-Mexico border more dangerous for American citizens, he’s done a fine job. His policies have opened our southern border to the world, creating an epic mess.

“It’s the worst I’ve seen it,” says Ron Colburn, retired national deputy chief of Border Patrol. “When I entered Border Patrol in 1978, not beyond my wildest imagination could I have pictured it this bad.”

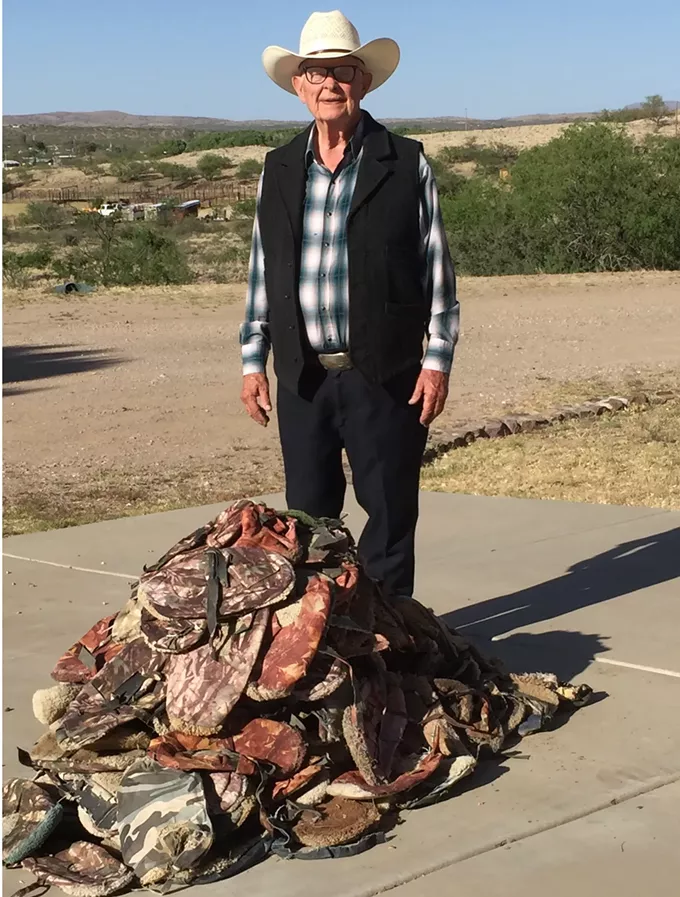

Across the agency’s 262-mile Tucson Sector, from Douglas and Nogales, to Arivaca, Ajo and onto the Tohono O’odham Reservation, illegal crossers keep coming, lines of them wearing camouflage clothing and carpet booties to throw off trackers.

They trek over our mountains and deserts and cram into the trunks of load vehicles. Border Patrol is overwhelmed. Their radios squawk nonstop.

In fiscal 2021, Tucson Sector agents recorded 120,509 arrests, almost as many as the previous four years combined, according to agency statistics. So far in fiscal 2022, arrests are up 73 percent over that.

A growing number are not the desperately poor of popular belief. They dress in nice clothes and have newer iPhones than the agents who encounter them.

Some say arrests looks worse than they are because of a Trump-era public health policy, still in effect, intended to deal with COVID. Known as Title 42, it allows border officials to quickly push crossers back into Mexico. About 35 percent of them are arrested again, boosting the numbers.

But annual arrest numbers have always included multiple arrests of the same individual, and Border Patrol says the arrest recidivism rate has remained steady at around 35 percent since the 1990s.

The argument also fails to acknowledge the large number of gotaways, those who are spotted but evade capture. This summer, after Biden forced him out as Border Patrol’s chief, Rodney Scott said in TV interviews that there were more than 400,000 known gotaways across the Southwest border last year.

A fourth of those—120,000—passed through the Tucson Sector, according to the agency. These are people walking into the country unchecked for possible criminal backgrounds and almost certainly unvaccinated.

Of those arrested in the Sector last year, 1,743 had prior criminal convictions in the U.S. The worst of the worst show up on the Sector’s Facebook page as significant arrests (see sidebar).

On a single day, Oct. 25, agents working near Bisbee arrested three felons previously convicted in the U.S.—for sodomy in Georgia, for lewd and lascivious acts with a child in California, and for assault with a deadly weapon, also in California.

To be sure, these dangerous individuals make up a small percentage of those crossing. But we can also be sure there are many more criminals of every kind among the gotaways.

The Facebook page also lists failure-to-yields, in which law enforcement lights up a suspected smuggler and the driver takes off. Their number has increased, along with wrecks, causing fatal crashes on Arizona’s highways.

In June last year on the Arivaca Road, a smuggler wreck killed one and sent seven to the hospital. In Pinal County last August, a Jeep Liberty stuffed with 11 people crashed on I-10, killing three.

In November in Cochise County, Wanda Sitoski, 65, from Benson, was killed when an alleged smuggler, a 16-year-old boy from the Phoenix area, ran a light and hit her. Sitoski died instantly. She was headed to her birthday party.

“Our pursuits are off the charts,” says Cochise County Sheriff Mark Dannels. “It’s twenty-four-seven.”

Picking up illegal crossers and driving them away from the border has become big business. The smuggling gangs solicit drivers, many of them American teenagers from Maricopa County, on WhatsApp, Snapchat and Facebook.

They’re paid $1,000 for every illegal they stuff into their car.

In December, Dannels stopped a car for speeding. The occupants, male teenagers from Greenway High School in Phoenix, admitted they were there to pick up illegals. He clocked them going 23 mph over the speed limit.

Two hours before, DPS and Border Patrol had them going 105 mph.

“These are kids coming to my county to take part in a criminal enterprise with a drug cartel,” Dannels says. “That’s upsetting.” He says that between 900-1000 cars a month come to Cochise County to make these runs, according to figures provided to him by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

The impact on the Cochise County’s finances has been dramatic. Between July and the end of the year, Dannels says the cost to handle border-related crimes at the Cochise County jail was $830,000.

“We have so many people working long hours it’s kicking our butt,” he says, adding that the state recently stepped up with money to help defray some costs.

These highway wrecks are heartbreaking. But on the border, there’s plenty of heartbreak to go around.

Roughly every two weeks, at around 1 a.m., smugglers push a group of up to 180 people, many of them unaccompanied children, across the border near Sasabe, about 70 miles southwest of Tucson. The kids, shivering and scared, some as young as 8, wait there until Border Patrol can pick them up.

It’s a tactic. The agency calls it task saturation.

The smugglers have scouts on the mountains on the south side and sophisticated communication networks on the north side to monitor every move by law enforcement. They know the kids will be bused to Tucson for processing, and exactly how long that will take.

When the agents leave, the smugglers bring in people and drugs, including those little blue fentanyl tablets. Between April 2020 and April 2021, the U.S. had 100,306 overdose deaths, 274 a day, according to Centers for Disease Control.

Some 62,338 of those were from synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl. The Drug Enforcement Administration says that more than 95 percent of the fentanyl that reaches American cities comes across the Mexican border.

Pima County mirrors the national trend. As of December, there had been 436 overdose deaths in 2021, 58 percent from fentanyl, according to Mark Person, program manager for the Pima County Health Department. The final count for 2021 isn’t ready, but he’s certain it will be the third straight record-setting year.

Numbers from Pinal County illustrate the fentanyl surge. Sheriff Mark Lamb says his officers didn’t seize any fentanyl pills in 2018. In 2019, they seized 700 pills and in 2020 the number was 200,000.

From January through December of 2021, the count soared to 1.2 million pills seized. Most are shipped across the country, and there’s a lesson in that.

“People think this is an Arizona problem or a Southwest problem,” Lamb says. “But it’s an American problem. It’s a major, major plague.”

Here’s a second important lesson: The country sees the open border as an immigration issue. But it’s more about crime.

The cartel bosses who control all the land on south side of the line and ‘own’ trails on the north side, aren’t in business to help crossers achieve a better life. There’s no Statue of Liberty on the border road near Sasabe.

To them, those kids waiting in the dark are cargo to be exploited, nothing more.

For the cartels, it’s about money. No child, family unit, or single adult steps across the line unless the cartel boss approves it, and the profit is staggering. The average pass-thru fee is $8,000 per person, and in fiscal 2021, there were 1.6 million arrests at the Southwest border, the most ever recorded.

In the current chaos, the stretch of remote Coronado National Forest land from Nogales west to Sasabe, about 40 miles, is especially hard hit.

In the adjoining Mexican state of Sonora, cartel factions are fighting a brutal war for control of lucrative smuggling corridors, and some of it is spilling over. Arizona residents have reported, and federal sources confirm, four shootings on that frontier in recent months.

On Sept. 6, two men who’d been shot and wounded in Mexico scrambled across the line south of Arivaca Lake seeking medical care. In the same area on Sept. 16, it happened again, a man wounded on the south side fled north.

The next day, Sept. 17, Border Patrol agents working on the line near Holden canyon reported shots fired from the south side. The gunmen might’ve been shooting at the agents, although that is unclear. The agents didn’t return fire and were not hurt.

On Oct. 13, on the border in California Gulch, roughly the same area, gunmen on the south side fired shots in the direction of workers for Fisher Industries, the border wall construction company. No one was hit. The company did not return a call seeking comment.

Says Ron Colburn, “That’s the cartel saying, ‘We own this border now. If you get in our way, we’ll shoot you.’” The latter two incidents occurred on land rancher Jim Chilton leases from Forest Service. After the Sept. 17 shooting, he received a call from that agency saying the shooting was done by three men carrying long rifles and warned him to stay away from the area.

At other times, Chilton has made appointments with Forest Service personnel to work near the border, but they’ve cancelled because of the danger.

At the urging of his wife, Sue, Chilton has stopped going alone to his border pasture. When he does go, he is sometimes accompanied by two friends, retired L.A. County sheriff’s deputies. They serve as his private security.

James Copeland, district ranger for the Nogales Ranger District of the Coronado National Forest, didn’t respond to messages seeking comment.

The future promises more of the same as the number of Border Patrol agents drops. The Tucson Sector is down 900 agents over the past two years – to 3,300 from 4,200 – and that number will likely fall to 2800.

As one agent said, “My expectation is we’ll continue to see an increase in hard narcotics coming across the border. That will draw rip crews and armed encounters. I’m confident that will take place over the next year or two if we continue down this path.”

Chilton is seeing it already. Between November of 2020 and November of 2021, his motion-activated cameras identified 830 drug smugglers and illegal entrants on his land. But that represents a fraction of what’s crossing.

He estimates there are upwards of 200 smuggling trails on his ranch and he has cameras on three of them.

About five miles of Chilton’s border with Mexico is blocked by the 32-foot wall built under President Donald Trump. But it’s unfinished.

Although the Department of Homeland Security recently said it would close small openings in the wall, there’s still a half-mile opening along Chilton’s land, and multiple water gaps through which smugglers can easily enter.

“Since President Biden stopped the wall last Jan. 20, we’ve seen a huge increase in traffic,” says Chilton.

His neighbors, Tom and Dena Kay, have, too, and they’re wary of the people crossing. “Their aggression is unbelievable,” Dena says. “They have no fear.”

On the hill right outside the Kays’ back door, illegals have a layup where they wait for load drivers to take them to Tucson. The site is littered with trash.

"Over the last two years of Trump, we didn't see any illegals around here at all," Dena says. "Our fences were not torn up like they are now. Tom wasn't nervous about going to the border by himself and we didn’t feel like hostages in our home. Now we’re reluctant to leave the house unguarded.”

For several years, Dena had stopped carrying her .38. But she has gone back to keeping it close, and she watches for every alert from her faithful watchdog, a Rottweiler named Sherman.

What would you call a neighborhood like that? How about Bidenville?