In the opening work at a small show about women printmakers, Tucson artist Kathryn Polk sends a clear message: "I make prints, not pies."

Her color etching pictures a rapturous woman in a studio packed with all the tools of the printmaking trade, from roller to inks to press. Wearing an apron and a pink dress with a pert white collar, she looks a bit like one of those happy housemakers in a 1950s ad. And that art roller in her hands could be mistaken for a baker's rolling pin and she's got a piece of pie on the table. But this woman is no baker. She's an artist and she's gonna smash that pie.

Polk's is the only piece in the 54-work show that's not part of the UAMA's sterling print collection, much of it acquired by the late, great Peter Bermingham, longtime director of the museum. But the curators, the museum's Olivia Miller and UA art prof Cerese Vaden, evidently thought Polk's biting metaphor of a piece was too good to pass up.

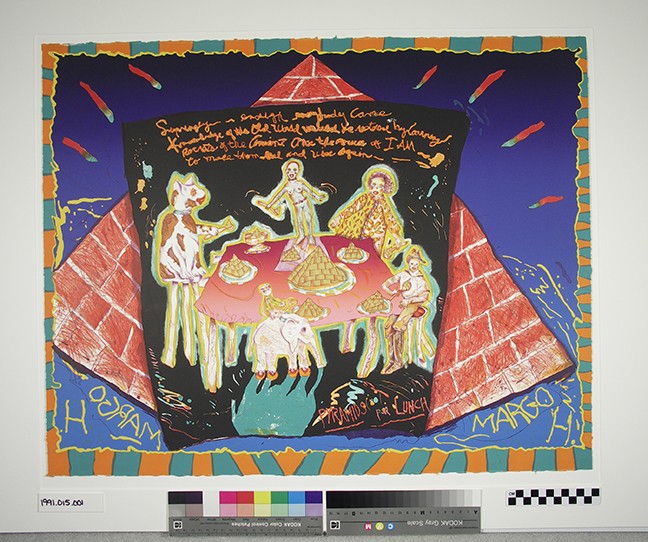

Their energetic exhibition, Subject to Change: An Evolution of Women Printmakers, surveys prints of all styles, from social realism to fantasy. There are bright crazy color works like "Pyramids for Lunch," a 1984 color lithograph by Margo Humphrey of a mad-hatter tea party where pyramids are on the menu, and finely patterned abstractions like Eleanore Mikus's" "Tablet Litho 2," a 1968 black and white whose lines and scratches conjure up books on shelves. The excellent Taos artist Gene Kloss made a beguiling regionalist etching of the local landscape, "Ranchito-New Mexico," in 1936.

There's even another dark kitchen satire. "Third Eye Watching," a 2008 photo intaglio by Janet Ballweg, is dim and claustrophobic kitchen without windows. The creepy patterned wallpaper echoes the yellow wallpaper that drove a desperate housewife to madness in Charlotte Perkins Gilman's early feminist short story.

Vibrant and rebellious as the works are, the curators point out that women were long left out of printmaking—a genre that includes woodcuts, lino cuts, etchings and lithographs.

In the mid-15th century, when new technology and the availability of paper made printmaking possible in Europe (the Chinese had pioneered it centuries before), artworks could be reproduced and sold inexpensively for the first time. But this "cultural revolution," as the curators call it, largely bypassed women. There were some women artists then, most of them raised in artist families and trained by artist fathers or other relatives. But the heavy equipment required for printmaking sidelined even these intrepid women.

That changed over the centuries. Mary Cassatt, the American Impressionist painter—whose father opposed her career—is not in the show, but she was making gorgeous color prints of her trademark mother-and-child subjects by the late 19th century.

The earliest piece in the UAMA exhibition is an 1898 etching by the renowned German artist Käthe Kollwitz, a printmaker and painter whose father encouraged her talent early on, as Cassatt's father did not.

Known for her piercing images of workers, the poor and victims of war, Kollwitz is represented here by "Pregnant Woman with Folded Hands," an intense and troubling portrait. The woman holds her hands over her swelling belly and looks sadly into the distance.

A couple of post-World War I pieces reach for tranquility in nature. Bertha E. Jaques's "Spiderwort," a color etching from 1929, is a delicate rendering of subdued blue flowers on gracefully curving stems. But right after the financial crash of 1929, Elizabeth O'Neill Verner etched a dark thicket of trees in "Live Oaks, Mulberry Castle," circa 1930.

The disastrous Great Depression paradoxically gave both women artists and printmaking a significant boost. By 1933, the unemployment rate in the U.S. was close to 25 percent; in a labor force of 52 million, nearly 13 million people had lost their jobs. Faced with this crisis, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Works Project Administration to put Americans back to work. Over the course of its eight years of operation, from 1935 to 1943, the WPA hired an astonishing 8.5 million workers.

The work teams, paid decent wages, built bridges, roads and public buildings all over the country. WPA workers built Tucson's old Pima County Hospital, now demolished, and the nine bridges in Sabino Canyon. (Another federal work group, the CCC, handled Sabino's stone picnic tables and shelters.)

But the WPA also invested in artists, with some 10,000 working in the Federal Arts Project, famously making post office murals, among other things. A sub-group, the Graphic Arts Project, specialized in hiring printmakers.

Peaking at about 800 printmakers in 1938, these artists went to their federal job each day, earning a decent wage of $100 a month. And, as former UAMA curator Dr. Lisa Fischman wrote dryly in an essay on the project, "For the first and only time in American history, women were paid the same rate as men."

The artists produced many thousands of prints, and when the Depression ended, the WPA donated many to institutions; the UA got 200. In 2005 Fischman organized a wonderful show of about 100 of the works.

It would be fun to have a re-do of her big exhibition, but Subject to Change does display five of the pieces. They're wonderful representations of 1930s style and of America itself. Ida Abelman does an evocative color portrait of a young woman that's part Expressionist, part Impressionist. M. Lois Murphy's expert woodcut "Hot Corn" is a social realist image of struggling rural people, some of them African-American, buying food at a street stand. And Kyra Markham's dishy black-and-white litho "In the Wing," of showgirls about to go on stage, is laden with an eerie Hopper-esque light.

Gene Kloss, it turns out, wasn't in the Graphic Arts Project, but she was the only etcher hired by another Depression agency, the Public Works of Art Project. Earning a federal paycheck, Kloss made countless luminous etchings of the New Mexico terrain, all of them treasures of an American time and place.