Craig Schumacher is hunkered down at his mixing board at downtown's Wavelab Studio on a hot Wednesday afternoon in late August, listening to a work in progress by Sergio Mendoza.

As the song plays over and over again, Schumacher taps his mouse, adding an effect here and tweaking an electric guitar lick there. He watches the music digitally unfold in jagged vertical lines on the computer screen, as green and orange lights flash on his mixing board.

Behind him on a small leather couch, Mendoza is listening intently. Mendoza has played keyboards with Calexico and DeVotchKa in recent years and has been pioneering his own indie-mambo sound with Sergio Mendoza y la Orkesta.

Now he's recording his first studio album at Wavelab and needs to figure out how to get the sounds in his head into a digital file that can be pressed onto an album.

Mendoza is listening for details only he can hear. The song isn't right. He's full of questions for Schumacher: What else can you do with it? What about that organ? A little more of the wood percussion? What's that effect? Can you move the vocals to the right?

Schumacher noodles around, and they listen again. They like what they hear.

"Good call, musician boy," Schumacher says.

"It's getting there," Sergio replies. "It's really close."

The painstaking process comes in the middle of a busy week for Schumacher. He spent much of Monday afternoon setting up gear at the Fox Tucson Theatre to help record a live concert on Tuesday, Aug. 23, featuring Amos Lee—with occasional backup by Tucson's own Calexico and the Silver Thread Trio—that was being taped for the syndicated PBS series Artists Den.

Schumacher himself climbed onstage with the band Tuesday night to play harmonica on "Jesus," a song on Lee's latest album, Mission Bell. The album, which debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard Top 200 list when it was released in late January, was recorded at Wavelab last year.

Being back onstage was "a really good time, for sure," Schumacher says. "Amos was really gracious to let me do it."

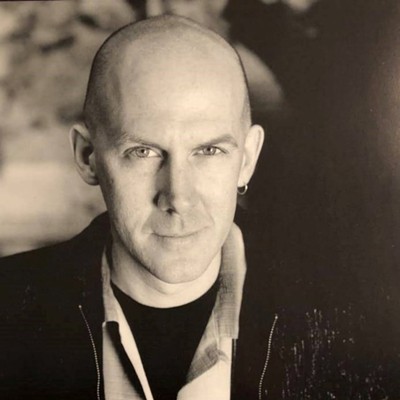

It wasn't too long ago that Schumacher, 52, wouldn't have had the strength for this kind of stuff. Earlier this year, he was diagnosed with head and neck cancer. The treatments were brutal—"it hit me like a sack a hammers," he says—but he's back on his feet and behind the board at Wavelab.

While he's now on the mend, Schumacher's medical bills have piled up. Even though he had insurance thanks to the employment of his wife, Karen Lustig, there were plenty of expenses that weren't covered—and on top of that, he hasn't been able to really work at Wavelab in months.

As he works to get back on his feet, many of Schumacher's friends are stepping up to help out. This weekend, artists who have recorded at Wavelab are coming to town for a benefit for Schumacher.

Calexico, DeVotchKa, Richard Buckner, Tom Russell, Nick Luca and Jon Rauhouse will be performing at Hotel Congress' HoCo festival on Sunday night, Sept. 4. Sergio Mendoza y la Orkesta will play the benefit's after-party.

On Saturday, Schumacher himself will be hosting a barbecue at the HoCo Fest that will feature another set of bands, including Tierra del Fuego, Greyhound Soul and Al Perry.

"I'm gonna have to rest up to have enough energy for it all," Schumacher says.

David Slutes, the entertainment director at Hotel Congress and a veteran of Tucson's music scene, says the benefit show will "help someone who has been profoundly important in the music community. What Craig did was put Tucson on the map in this niche way, with these wonderful artists coming specifically because of him. It made Tucson a creative hotspot. If we can't support a guy like this, what are we doing?"

Slutes has known Schumacher from the days when Schumacher played punk music with Al Perry and Hecklers about three decades ago at El Con Mall's Tequila Mockingbird, an unlikely hub of the live-music scene in the '80s.

As the Tuesday, Aug. 23, performance demonstrated, Schumacher still gets the occasional chance to climb onstage, but these days, he makes his living helping other artists capture their music for release to the masses.

He's been at it for more than two decades now. (And that's not counting the first recording studio he built in his garage, which he decided was a bad idea after a neighbor knocked on his door to let him know: "Enough is enough.")

Schumacher, who previously worked as a plumber, first opened up a recording studio (originally named 7 and 7 for its location at Seventh Street and Seventh Avenue) in a downtown warehouse in 1990.

Howe Gelb, of Tucson's Giant Sand, remembers writing a record in his head while driving from Joshua Tree, Calif., to Tucson back in the early '90s. He pulled his old '66 Barracuda right into the warehouse and unloaded his gear.

"I liked so much being in there, and the minimalism and the sound of that place, that we tried to make most of our recordings there," Gelb says.

Schumacher "always could pull out something in the mix, and he would do it fast, and he would stay at it until he got it done," Gelb says. "It felt like he was in your band with you while you were recording."

In those days, nobody had any idea that Wavelab would become a creative oasis for indie rock.

"We didn't know that people would look back on us and give the town credit for this sound," Gelb says, "but when they look at all these records, and they keep seeing 'Wavelab' on there, then you have people from all over the world coming in to get that sound."

Wavelab moved around downtown before settling a few years ago in its current home on Sixth Avenue, next door to Janos Wilder's Downtown Kitchen + Cocktails.

The studio doesn't look anything like the Hollywood stereotype of glass walls and sterile booths: It's a big room with sunlight streaming through skylights in a high ceiling.

Schumacher's control booth is set up in a corner of the room, where he has a mixing board, a computer and tall stacks of preamps and other analog recording gear—"lots of different flavors of tubes and solid state"—that he's bootstrapped together through the years.

Schumacher hooks his analog equipment into his Mac to create the Wavelab sound. He says a lot of people in the music biz these days are looking for something that they can't get out of modern digital equipment.

"There's a certain sound that you just don't get from the digital," he says. "It's just not possible. You put audio through transformers and resistors and transistors and capacitors, and let tape do its thing, and there's a sound on tape that you don't get on digital."

Joey Burns, the frontman for Calexico, says that Schumacher brings an artist's ear to a technical craft.

"It's a technical job that he's doing as he's manning the mixing desk and all of the outboard effects. But it is an art. ... Instead of being strictly archival, he's putting a lot of artistic love and thought into these mixes," Burns says.

Burns has been recording with drummer John Convertino at Wavelab since the early '90s, when they played in Giant Sand and the Friends of Dean Martinez.

It was while recording Calexico's second album, 1998's The Black Light, when Burns walked into the studio early one day and heard some mariachis recording an album. He realized that he wanted that sound on the record—and it led to the Latin-flavored indie-rock sound that propelled the band into the international spotlight.

Burns and Convertino have collaborated with a collection of indie-rock bands and singer-songwriters at Wavelab, from Sam Beam of Iron and Wine to Neko Case. Schumacher credits them as being a big part of the Wavelab sound that has brought attention to the studio.

"We've been lucky," Schumacher says. "The cool thing is, I've been able to establish a niche through the location and the sound. There's a sound that we get that's desert-y and dusty and whatever you want to call it. Most of it's because of John Convertino's drums and Joey's musical sensibility. ... We've always embraced our environment."

As proud as Schumacher is of his hybrid mix of analog tubes and digital Pro Tools, his true love is his collection of keyboards and guitars that he assembled by browsing downtown's Chicago Store and scouring the newspaper classifieds and Craigslist. He can rattle off details about them: Here's a Vox Continental organ like the one that Question Mark and the Mysterians used on "96 Tears." Here's a Hohner Clavinet like Stevie Wonder played on "Superstition." Here's a Wurlitzer Model No. 270 Butterfly Baby Grand mounted in a faux spinet piano case.

"I've never seen anything like it," says Tom Russell, an El Paso-based singer-songwriter who will be performing at Sunday's benefit. "It reminds me of a place that The Band might have recorded. It has a vibe that's timeless, and in these days, when any kid can record a record on his iPhone, it's nice to see that kind of combination of vintage stuff and a warm room, and yet he can still use digital technology there."

Russell recorded several tracks of his new album, Mesabi, which is due in stores later this month, at Wavelab.

"Craig's a master at using the room," Russell says. "He has such great ears. He's a musician, first of all, but he understands music and songwriting. It was the perfect situation for me. I like the sound of stuff that's coming out of there."

Jon Rauhouse, a steel-guitar master who has recorded his own albums while also backing musicians including Neko Case at Wavelab, says he's tracked in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, but Wavelab "is far and away my favorite studio."

"He's a good person and solid Joe, but as far as his ability, he's a killer engineer," says Rauhouse. "He knows how to do it, knows the gear and knows how to help people. It's awesome to work with him."

Multi-instrumentalist and songwriter Nick Luca, who is just wrapping up a tour as part of Iron and Wine in Europe, worked at Wavelab as an engineer and studio musician for about 15 years before he moved to Los Angeles in 2009.

Luca, who is also coming to Tucson for the HoCo benefit, met Schumacher when he went in to record a single as part of a compilation of TAMMIES winners that was put together by Jeb Schoonover and the Tucson Weekly.

"My jazz group, Greasy Chicken, went into Wavelab to record my song, and later on, he said, 'Hey, you want to start hanging around the studio? I could use some help.' And it turned into a 15-year gig."

Luca remembers some lean years in the 1990s.

"It's a pretty tough business just being a studio owner in general, and to make your own music and help out the community," Luca says. "When we first started, it was a pretty haphazard operation. There wasn't much income. But over time, we started getting lucky, with more people coming and booking time. It just slowly built, and 10 years after that, we were slammed—still not making tons of money, but able to survive."

Through those early years, Luca remembers that Schumacher was always generous with local musicians who wanted to record at Wavelab.

"Craig's always been a fan of helping the new young artists—which Calexico was at one time."

Today, the young artist getting help is Sergio Mendoza. Schumacher spends most of that Wednesday with him as they slowly but steadily polish the song.

"The sound that Sergio recorded is not the sound that he wants to hear," Schumacher says after they've wrapped up the work. "He really wants the vibe of this record to sound like an older '40s or '50s record. ... Sergio has a vision, and he knows what he wants, but he's young, and this is his first experience, so he isn't quite communicating what it is that he wants. But he's gotten a lot better at it over the course of mixing."

After all that work on the details, "it came out great," Schumacher says. "It's really cool now."

It takes a special kind of ear to assemble—and occasionally deconstruct—music so it can be pushed through the wires and turned into a recording.

"It's a special skill to know what equipment is going to get you the desired effect, with all of those racks and racks of gear," says Luca. "Craig is particularly good at it. It's years of practice and studying and talking to people and reading about how the greats did it."

While he was fighting the cancer, one of Schumacher's biggest fears was that the chemotherapy might mess with his hearing. Fortunately, he got through each round without any permanent damage.

Schumacher learned he had cancer after doctors had tried to remove what they'd hoped was just an infected tonsil. Instead, it was a tumor that had begun growing near his carotid artery.

He spent a good part of the spring and summer knocked down by the one-two punch of chemotherapy and radiation. He lost nearly 60 pounds, dropping from just less than 250 pounds to about 190.

The treatments came to an end in late July, but he's only now recovering his ability to swallow solid food.

"I'm not in danger of gaining any more weight, seeing as how I've dropped a few pounds just in the last few days from just working and not eating as often as I should," Schumacher says.

The doctors tell Schumacher that they think they have the cancer beat, but he has a lot of follow-up to do over the upcoming months. In the meantime, he's getting back to work.

Sergio needs to get that record finished. Calexico is overdue for a new studio release. Neko Case needs to record some new music. That Amos Lee PBS special needs to be mixed.

"I'm happy to not be lying around the house and be down at the studio again," Schumacher says. "I'm glad I can sit down and do a mix again. It's all feeling good."