Truman Capote was a beautiful young man in 1955.

At 31, he was already an acclaimed writer. His first book, the novel Other Voices, Other Rooms, published when he was just 24, had been a sensation, winning praise and opprobrium alike for its unapologetically gay leading character.

His friend Richard Avedon, age 32 at the time, made a portrait of Capote that happy year, when his body was young and his writing already recognized. In the photo, he tilts his head to one side, his eyes closed, his lips sensuous. He pulls his arms to the back, showing off his bare chest.

Enveloped in a white light—Avedon's signature white background—he looks like an erotic angel.

Nineteen years later, Avedon photographed Capote again. The change is shocking. At 50, Capote's head has gone all Winston Churchill: his face is sunken and jowly, the skin blemished, the hair sparse. His once-naked flesh is now covered in dark clothes. Even the white background has shrunk.

Worst of all is his expression. His puffy eyes are open, but barely, and he doesn't seem to focus. He looks world-weary and cynical, his youthful joy all but gone.

These extraordinary views documenting the aging of one man are just two of the many arresting works in Richard Avedon: Relationships at the Center for Creative Photography. Curated by the center's Rebecca Senf, the exhibition is some 80 photos strong, with most dating from the 1950s through the 1970s. (Avedon died at 81 in 2004.)

To create his distinctive work, all black and white, in sizes from small to monumental, Avedon used a large-format camera that allowed him to photograph his subjects up close. The intimate, minutely detailed images that resulted won Avedon commissions in top magazines at a time when they were thriving. When he died, suddenly, he was at work on a democracy project for the New Yorker.

Though Avedon donated some 456 works to the Center (you can see all of them in streaming slide shows on four iPads in the gallery), this is the Center's first show of the artist in more than 10 years. The last one, In the American West, was a fascinating look at Avedon's later-life photographs of western down-and-outs toiling at ranches and mines.

The current show is more in keeping with what Avedon is best known for: imaginative fashion shoots and incisive portraits of the famous.

The show abounds in marvelous pictures of artists (a monumental Louise Nevelson, Jasper Johns), politicians (Jimmy Carter, Dwight D. Eisenhower), writers (Carson McCullers, Gabriel Garcia Marquez), dancers (Rudolf Nureyev, Merce Cunningham), actors (Audrey Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart), musicians (a young Bob Dylan) and poets, including a priceless Allen Ginsberg nude with his partner and elsewhere at a gathering with his New Jersey family.

A portrait of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is especially tender. It was shot in 1963 when he was a lanky high-school sensation, just 16 years old. Avedon was still making some portraits in real-life settings back then and he photographed Kareem all suited up, basketball in hand, in a neighborhood playground in New York City. The apartment buildings behind the teen block the horizon, but nothing would stop this confident player: he would grow to be 7 foot 2 and would become a legend in the NBA, the second-best in its history.

In another work, power figures in politics are lined up in a grid of small portraits against the typical Avedon white background. Commissioned by Rolling Stone in 1976, the magazine published no fewer than 69 of these photos, filling up the entire issue. To his credit, Avedon included women. In the sampling of 16 shown here, a bold Barbara Jordan—a rare black congresswoman representing Texas—stands out, and so does Katherine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post, which had lately helped topple President Nixon.

The turbulent 1960s are evoked in a shot of Julian Bond in a civil rights march in 1963—Avedon slightly blurred the other marchers to put the emphasis on the charismatic Bond—and in a group shot of the Chicago Seven, the Vietnam protesters who were arrested in the violent Chicago "police riot" in 1968.

A series of sequential portraits of George Wallace, the racist governor of Alabama, chronicles his downfall; in the first two, from 1963, he's the arrogant bigot, glaring at the camera. In 1976, he's still governor, but he's in a wheelchair, paralyzed by a would-be assassin during one of his two failed attempts to become a candidate for president. In a nice irony, curator Senf has placed Malcom X, pictured in 1963, right next to the fallen bigot.

There are a few celebrities in the show famous for being famous, or rich. A photo of two European pseudo royals, Vicomtesse Jaqueline de Ribes and Raymundo de Larrain, in 1961 New York is a hoot. The suavely-groomed duo—she in a lacey evening dress, he in a tux—both peer into her hand mirror to check out their hair and their hauteur. They look like relics of the ancien régime—and a good excuse for a new French Revolution.

But Avedon's portrait of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor is no joke: it's a serious revelation of the hapless, hopeless lives of the Nazi sympathizer who abdicated his throne for love and the woman who became his wife. Photographed at New York's Waldorf Astoria Hotel in 1957, some 20 years after the abdication, the pair cling together joylessly, their faces etched with what looks like despair.

Avedon made a sub-specialty in portraits of married couples. The most spectacular here are large-scale images of renowned photographer Robert Frank and sculptor June Leaf. Posing them separately and together, Avedon caught their shifting identities as individuals and as partners.

In the fashion images, Avedon lets loose creatively. While the portraits are static, the fashion images are full of movement. In a 1957 ad, Cardin, the model Carmen leaps over a puddle in street in Paris. In 1970, Ingrid Boulting dances through an undefined modernist space, wearing a Dior coat. And dancer Cyd Charisse, moonlighting as a model, sails through the air in a diaphanous dress in 1961.

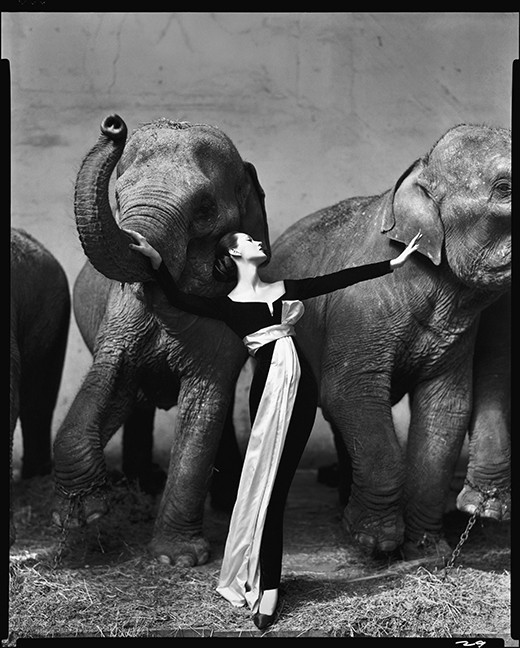

The most imaginative fashion photo here involves not only a model but three elephants. The model, Dovima, a frequent collaborator with Avedon, once said of their partnership: "We became like mental Siamese twins."

In this 1955 work, she stands in a Dior gown between elephants borrowed from a Paris circus. Her tall, narrow form contrasts with the animals' hulking roundness, and the light sash of her dress chutes downward, a counterpoint to one elephant's rising trunk. The work is all dark against light, straight lines against circles, and amidst this rhythmic composition Dovima flings out her arms in joy.