The first thing is the voice. A velvety, often hypnotic talk-swoon that lifts, and then, as if guided by a gentle Mort Shuman melody, dips into the nether regions of the human larynx, where its bass notes resonate throughout the cavernous room, before lifting up again.

"Ah ... ah, B12." The voice croons. "That's, uh, B12. ... This is a six-pack. ... No, we ain't building rockets here."

The voice banters with at least one gent here, about his date for later that night. Randy enough comments to get several of the blue-hairs going. The hushed giggles of a women's church group.

But this is no church group; this is bingo, man. And among the 35 or so folks of various genders, ethnicities and ages, it's mostly an old ladies game. It's a warm weekday afternoon in February at the Pima Alano Club in central Tucson.

Those at this bingo session are hardly dead-eyed or resigned, as I imagined they'd be. After all, this is a room that—with its long tables and wood-framed platitudes—doubles as a kind of museum to Alcoholics Anonymous. My own damn prejudice.

The lady seated in front of me, Sarah Rodriguez, plays with mind-boggling studiousness, even while working a chicken potpie. She creates, with lightning speed, deceptively simple bingo pattern variations like "six-pack" and "blackout," and her effortless tap-tap movements with a rose-colored dauber distract and intimidate.

She has cropped gray hair and wears a gray sweatshirt decorated with images of happy Native American kids. Game lulls allow her story: She’s widowed with two grown children. She lives "pretty far" from the Alano. She returns a few times each week for the bingo, a habit that’s lasted five years. Her fabulous grin when she recalls winning a thousand bucks here a few years back.

Sitting next to Rodriguez is her smoky-voiced friend Eva, and this pair, who alternate between English and Spanish when they converse, look to be in their late 60s or early 70s. They slay at bingo. Because I've never played, I interrupt them for instruction. Their patience teaches. In the bigger way I feel like a self-loathing fraud.

The women are dedicated, gentle in their ages. Like they’ve figured out how not to lament the past or dread the future. I don't to strain to recall my own grandmother, a graceful and beautifully put-together woman, instinctively matriarchal and brilliant. Bingo can be sad.

* * * *

Michael Rothblatt is the bingo-caller with that voice.

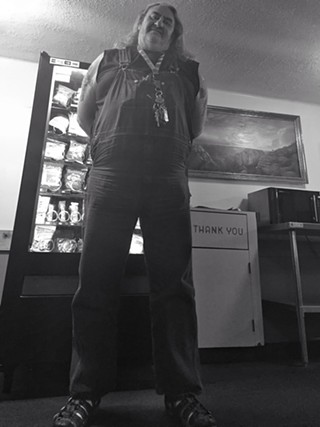

After leading the two hour-plus hour game, he moves through the club bumping knuckles with regulars. He's a faded ’70s arena-rock star or a Sons of Anarchy cast member—a stature and girth of real presence. Fold fingers into devil horns and hoist them unironically in his direction. He wears a black sleeveless t-shirt under blue overalls and a backstage-ready neck lanyard that dangles keys. Long, iron-gray locks, arm tats. Teeth imperfect from years of hard road.

My favorites are the fuckups. Like those forced off the playing field to engage in a gnarly battle with life-derailing addictions, for survival and excuse, only to emerge battle-scarred on the other side in various degrees of intactness, but with some sense of solidified selfhood, and the wisdom of giants.

Rothblatt is a giant, literally. Looms in at 6' 8."

"I go years without meeting anybody taller than I am," he says. Off mic, his voice rumbles like a busted muffler on a rusted-out Ford Ranger. "When you're as big as I am, you're a celebrity because everywhere you go people remember you. And, yeah, I'm kinda self-conscious about it."

The 59-year-old made it to the other side. He overcome gnarly booze and coke addictions (sobered up for good in ’95), and a motorcycle accident, among other things. He worked more than three decades driving trains between Tucson and El Paso, Texas for Southern Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad. He suffers hearing loss, which explains his disability retirement from the railway.

"My shift for years was 12 hours straight driving a notch-8 throttle locomotive,” he says, lifting thick, dark eyebrows. “It's fuckin' loud!"

His right shoulder tat is curious. An Irish clover inside a small Star of David, inside a triceps-long Celtic cross. He says the Star of David is a tribute to his Jewish dad and the clover a nod to his Irish-Catholic mom.

This son of a military pop was born in North Carolina and raised in El Paso. As a teen got caught with weed so he enlisted in the Army, just before the ’75 fall of Saigon. Discharged with a good conduct medal, that’s when he began on the train. "My aspirations were to get the G.I. Bill and play in a rock band."

Rothblatt can talk days about the science of railway locomotion ("There's so little friction that it's the closest thing to flying without leaving the ground") and recite each railroad crossing between here and El Paso. He talks euphemistically of his own sober life while referencing other rock 'n' rollers not so lucky— Type O' Negative’s Peter Steele, or Jani Lane, who drank himself to death. The rowdy cover bands in which he played bass through the decades. There’s the A.A. dance band Bleeding Deacons, and the '80s Rush tribute combo Steel Caress, which soared in El Paso, before the railroad transferred him Tucson in the late '90s.

A piece of his heart stills resides in that border town. He’ll rattle off storied exports with provincial pride. "Sharon Tate, Debbie Reynolds and Granny from The Beverly Hillbillies."

He could’ve been one of the infamous. While studying martial arts with his stepson "in an effort to get closer to him," low-budget exploitation specialist César Alejandro cast the giant in a kung fu movie, the '99 trash-epic Border Wars. They'd shoot scenes in Spanish, and English.

His character "Cholo Number 4" had no dialog, but he got to use nunchucks. His shot at the big-time evaporated when the film appeared with his name misspelled in the credits.

Under the moniker Ghingus Chingus, Rothblatt in 2011 wrote and recorded an album called Red Leaf. The heady chunk of thumping classic rock was mostly completed in Florida with backing musicians and help from his daughter Sarah, who continues to work in the music biz.

Talks of his cousin, Martine Rothblatt. He discovered she was transgender after seeing her years ago on The Phil Donahue Show. Martine’s now a billionaire attorney, author and social activist who, among other things, created Sirius Radio. She's the highest paid female CEO in America, and a leader in the still-ridiculed sciences of transhumanism and technological immortality, where mind uploading isn't considered far-fetched.

"She's one of the people who's trying to put a soul in a computer; they say they're about 30 years away." Rothblatt laughs. "To fundamentalist Christians she's the anti-Christ."

Rothblatt can yak, the side yarns roll careening boxcars. His early desires to become a Catholic priest, or how he married the same woman twice, or the one time he was asked to join Ronnie James Dio's security team. The booze, the cocaine, and drivin' that train. He talks of spiritual quests that rose from gratefulness—he really had to sober up to raise his step kids and his biological daughter.

When he needs it, this gentle giant has that spellbinding bingo-sing. Able to guide a whole universe inside this dusty, freestanding edifice down on East Pima Street, over near Columbus Boulevard.

Michael Rothblatt in the bingo-caller chair.

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "29441156",

"insertPoint": "1/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"component": "27651162",

"insertPoint": "10",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "29441158",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "10",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "29441159",

"insertPoint": "1000",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "15",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]