In early December 1992, 16-year-old Corinne Schram and two girlfriends headed to see the Grateful Dead at the Compton Terrace Amphitheater near Phoenix, driving up I-10 in Schram's Daihatsu Charade hatchback. Schram was headlong into teen rebellion then, the parties, the drinking, the drugs. All of her friends and boyfriends were older, a concerned mom’s nightmare. People her own age bored her. She attended public school, mostly in the advanced GATE (Gifted and Talented Education) program, and was to graduate high school a year early. She hated it, so she quit.

Schram was in the front passenger seat, and they were somewhere near Casa Grande. The girl driving turned to say something to the girl in the back, got distracted, and the little Daihatsu jerked out of its lane and swerved off road into the median. She over-corrected, the weight and momentum of the turn was too much and the car flipped.

But they were lucky, because no other cars were involved. They were lucky because investigators determined that the accident wasn't alcohol-related. They were lucky because the driver miraculously emerged from the crash unscathed. They were lucky because the windows of the Daihatsu were large enough to accommodate the girl in the backseat, so she hurtled through it into the cold air and only suffered a broken collarbone and dislocated shoulder.

But Schram wasn't lucky. Or maybe she was, if you consider the number of corpses that freeway has given up. She was found alive and broken, hanging from the wrecked car. Her head and face had slammed so hard against the freeway that it snapped her neck. She was airlifted to Good Samaritan hospital in Phoenix. She doesn't remember anything at all about the crash, or even any precise moment waking up in the hospital to the horrific discovery that she couldn’t move. Or how she needed many surgeries on her face, jaw and neck.

* * *

Imagine surviving a catastrophic crash in the worst imaginable way. You can still detect alarmed expressions on loved one’s faces, the too-serious tones of surgeon voices and false empathy of strangers. The florescent lights. You can smell the antiseptics and sterile linoleum floors, even the injuries and deaths around you, but little else. You want to die, but you can't even commit suicide but that’s impossible because you no longer can walk or move your arms or fingers. You're forced to depend on someone else for every movement, every necessity in your life, except for your head movement and the thoughts inside of it.

Forget dreams of the future, those that can lift a kid from spiraling youth. Forget it all. In this world you can't lift a fork to your mouth to feed yourself or brush a tickling hair from your face, much less reach out and touch another human being.

Then imagine somehow shifting that story—that self-narrative of utter defeat, isolation and loneliness—to something that's perhaps more complex and nuanced—a storyline mixed with a fierce yen to survive. It’s not blind faith. It’ not some god. It's you. It's all you in the center of an indifferent random universe ruled by chance and tragedy.

And then imagine telling yourself, and your skeptics, this: Fuck it—I'm going to go to college. And then: Fuck it—I'm going to go to law school.

That's what 39-year-old Ms. Schram did. She's a public defense attorney at Pima County Juvenile Court, and has worked in that capacity for seven years.

* * *

Butterflies with spread wings, enclosed in framed cases, decorate walls in Corinne Schram's quiet bedroom. It’s painted in mood-lifting light pastels, and natural light streams in through big windows. A calico cat sleeps on a paisley comforter in the middle of her made bad. This central-Tucson house, which she shares with her mother and seven cats, is similarly airy and lazy, smells of flowers, and faintly of furniture oil. The Salt Lake City-born Schram has lived here since moving to Tucson when she was three years old.

She talks about life and her relationship to the world. There's an air of dignity about her, in her personal insights, in the candid way she offers them. That she’s unable to move in a wheelchair, in the center of her room, is less a definition of who she is than it is a distraction and I can’t pretend to even understand what it means in practical terms. Can’t pretend to understand much.

Does she ever dream of living a different life?

"There's no point of having dreams of a different life because it's not ever going to happen."

Does she get lonely?

She nods. "Of course." A long moment passes. She adds, "Everybody does. But then, at the same time, it sucks never having time alone. My only time alone time is when I'm reading or sleeping."

She needs caretakers. She needs her mother Katharine. In the first four years after the crash, until she received a personal injury settlement, it was Schram’s mother who cared for her—the feeding, the bathing, the dressing, the driving, everything. Her father wasn't around much after the accident, and he has since remarried. Her one sibling, a sister who now lives out-of-state, was traumatized. "She went through years of depression and survivor's guilt," Schram says. (Schram three much-younger step-siblings on her dad's side live in the Czech Republic).

It wasn't easy getting there. Schram enrolled at the University of Arizona, graduating with a B.A. in philosophy. She earned her law degree in 2007. She'd have a caretaker in class with her, or occasionally classmates would turn book pages for her. The writing part wasn't easy either, as voice-activation software was, and is, problematic. She took a full school load, “same as everyone else.”

Her three years in law school weren't intellectually challenging, and she wasn’t “gung-ho" about going. But law, in pragmatic terms, was something she needed to do, considering how quickly her settlement money was evaporating—caregiver expenses alone were costing at least $60,000 a year. She says, “I had to do something that I could potentially make money doing, as well as physically do."

And becoming a public defender?

"I didn't choose it, it chose me. I was putting out resumes and that's where I got called. Pima County. I never wanted to go into criminal law, but I knew that if I did, it would have to be on the defense side. I couldn't prosecute. I couldn't be part of sending people to prison for non-violent offences. Stuff I don't believe in. I couldn't prosecute somebody for smoking weed. And the whole system I just think is so wrong and fucked up and prison is so awful, I just couldn't be a part of trying to put somebody there."

Mom says her daughter was never a self-doubter and always stood by her beliefs. This analysis might help explain how mom dealt with the tragedy when it happened. But their interactions can get prickly. Their relationship is hardly Grey Gardens, but it hasn't been easy. The love is obvious. Mom, an intelligent, sprightly woman who looks a good decade younger than her 73 years, can finish Schram's sentences, and vice versa.

“We’re close,” Schram grins, “Maybe closer than we should be."

"She can be stubborn," mom says. She relates a story about how years ago her daughter refused a catheter so she could wear jeans in her wheelchair.

"It's not stubborn," Schram interrupts. "It's conviction."

"You're right," mom says.

* * *

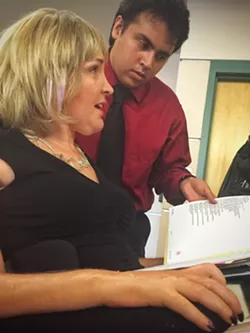

Irving Talavera reaches into Schram's purse, which dangles from the back of the wheelchair. He pulls out a pinkish lip gloss, opens it and carefully applies it to her lips. She utters a quiet “thank you” as he returns the stick to her purse.

Dressed for court, Schram looks great in a black, sleeveless top with an elegant V cut, beige slacks. Her neck-length blonde hair shows lavender streaks on the sides, a subtle rebellion.

There’s a stack of files piled on her lap, topped by her calendar book and a four-inch thick tome called Arizona Criminal and Traffic Law Manual.

"I usually don't carry a manual," the lawyer laughs, embarrassed. "It's for my depo hearing."

Schram's in the crowded waiting area outside one of many courtrooms inside the Pima County Juvenile Court building. There's a hearing for one of her juvenile clients. She has 35 active cases at the moment, and that’s a lot. The Juvenile Court is woefully understaffed; too many cases, not enough lawyers and probation officers.

Talavera, Schram’s assistant, flips her appointment book open to reveal the number of hearings scheduled for Schram that day. She'll tirelessly burn through five hearings in the next two hours—in and out of various courtrooms. Squeezed between the hearings are quick meetings with kids and their parents. She says probably 97 percent of her cases plead out, Few go to trial, and that’s a good; no one could handle even half that many.

Soon she meets with a set of bleary-eyed parents and their son, who has the gawky gait of a boy growing too quickly, filled of hormones and confusion. Their kid's welfare’s is important to them, as heard in their stiffly chosen words, seen in their concerned faces. It’s a porous relationship. Schram reassures them: Their son deserves less than a six-month probation.

Talavera wheels Schram into the courtroom.

The prosecutor, the boy's probation officer, the judge and Schram go around about the boy's shoplifting and weed charge. Schram recommends a lesser sentence than the six-month probation sought by the court. The urine tests are clean, he's doing well in school and hitting his 6 p.m. curfew. Judge Richard E. Gordon agrees, delivers a lesser sentence.

This is a glimpse of her workday, in a week strictly limited to 30 hours. She's physically unable to work more than that; long wheelchair hours create pressure sores. But Schram’s empathy for the kids almost sparkles it’s so obvious, but one would never get it watching her work. She’s a pro. Such things are revealed only in private. She’s reminded of her teen self.

"I wouldn't call them lost causes," she says later. "I don't think any of them are lost causes."