The Tucson Democrat's never held an elected post before. He got badly outspent and beaten in a run for the state House of Representatives in heavily Republican District 12 in 1998, the same year he was working on the Clean Elections initiative drive to create a program to supply candidates with public campaign funds.

Two years later, with the financial playing field leveled, he ran for a state Senate seat in District 12, only to lose to Republican Toni Hellon. At the same time, he worked on the Fair Districts initiative to strip lawmakers of the power to draw political boundaries in favor of an appointed committee that would draw politically balanced districts.

When the new Independent Redistricting Committee finished its work, Osterloh's new district was indeed more competitive. Republicans only outnumbered Democrats by 11 percentage points, down from the previous 12 percentage points.

But Osterloh's ambition had climbed beyond the statehouse; he's now aimed his sights at the governor's office. Not that he's causing Democratic frontrunner Janet Napolitano to lose any sleep. In an April poll of Maricopa County Democrats and Independents, exactly one person--not 1 percent, but just one person--expressed support for Osterloh. Napolitano was sitting pretty with 54 percent of voters supporting her in the primary. But Osterloh thinks he can turn all that around.

For the last four months, Osterloh's been seen bicycling through the suburbs, knocking on doors, begging for the five-dollar handouts to qualify for full campaign funding from the state under the Clean Elections Act.

That work is now paying off. He's turned in 4,812 of these contributions and will soon be cashing a check from the state for $409,950.

There's long been an assumption that any boob can fill a nominating petition, but it takes a viable candidate to convince people to give him enough money to run a top-notch media campaign. One of the major criticisms against Clean Elections is that it would give a lot of money to morons and wackos to run for office; Osterloh takes offense at the suggestion that his candidacy has fulfilled this prophecy.

Osterloh answers with the opposing assumption: that the traditional campaign fund-raising has allowed special interests to buy candidates with contributions.

"It boils down to this: we've got a bunch of crazies and wahoos in office now who just answer to the special interests," Osterloh said. "If you want to protect the environment you've got to make sure the oil companies aren't funding the campaign of the elected officials. If you want to have responsible growth you have to make sure that your elected officials aren't funded by the developers."

Osterloh's a new breed of candidate from the fringe of Arizona politics. Although his experience as a candidate is limited to two failed legislative bids, he's earned a 100 percent success rate in ballot initiatives.

Arizona allows citizens to put their own laws on the ballot. This power was further bolstered in 1998 with the Voter Protection Act, which made it next to impossible for the legislature to undo voter-initiated changes to state law.

"If you take a look at all the candidates out there, nobody has accomplished more that substantially changes the state for the better than I have and I've done that without being in an elected office," Osterloh said.

On the campaign trail, Osterloh is taking credit for the most state-shaking ballot initiatives of the last six years. Independent Redistricting, that was his. Healthy Arizona II, that was his, too.

His baby, though, is Clean Elections, the act that it made it possible for an outsider like him to run for the state's top office.

While Osterloh claims to be the primary author of Clean Elections, other campaigners have a different recollection. Those who remain of Arizonans for Clean Elections recall that the act was written by a lawyer named Hoffman, who specializes in, of all things, intellectual property.

"Mark was one of five people on a committee that came up with the concept and worked on the defining what it should look like," Hoffman said. "Mark did a first draft of it that had the principles involved but I acted as the attorney of the committee and took the concepts that they wanted and tried to turn it as close to statutory language as possible."

But in the case of the other initiatives, Osterloh's credit-hogging may be setting himself up to take the fall.

Healthy Arizona has led to the state enrolling about 100,000 more people in the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System since October, but it's also hammering the state's budget. The program has already burned through $100 million from Arizona's share of the tobacco lawsuit settlement and officials have had to dip into the state general fund for another $150 million. Costs are expected to climb even higher, according to legislative forecasters who estimate the number of people enrolled in the program will grow to 180,000 by the end of June 2003.

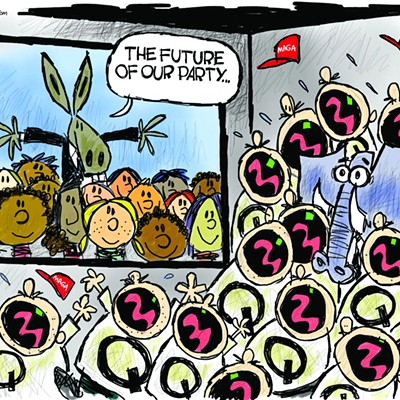

As noted above, the new legislative maps drawn by the Independent Redistricting Committee ended up with districts so unbalanced the Republicans now are hoping to win Senate seats in 19 of Arizona's 30 districts. Meanwhile, several lawsuits are holding up final approval with less than a month remaining before candidates are supposed to file nominating petitions gathered from voters within their still undrawn districts.

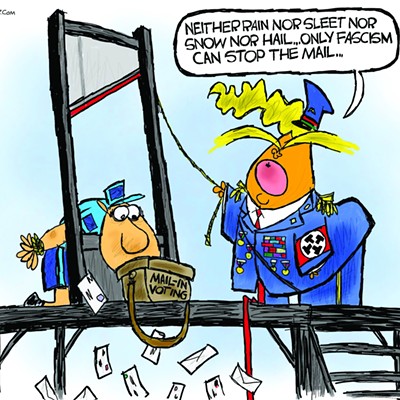

And if that weren't enough, a panel of appeals court judges is considering whether to strip the Clean Elections program of two-thirds of its funding on First Amendment grounds.