The truth was something more far more complicated. In fact, Lowell, Plath and Sexton were all dyed-in-the-wool formalists, masters of technique who introduced what, at the time, was shocking subject matter, and brought into sharp focus such themes as adultery, divorce, insanity and suicide. History is often a harsh judge, however, and the overall, lasting impression of these poets is that they simply spilled their guts on the page and aired their own dirty laundry with each successive, self-absorbed stanza, thereby cheapening the art form and making it safe for any angst-ridden teenager or bored housewife to scribble her innermost clichés into her marbled notebook between classes and Xanax pills.

This, of course, is complete nonsense. Here, for instance, is Sexton writing about divorce in her poem "The Break Away," in which she wonders where the love in her marriage fled:

Next I dream the love is swallowing itself.

Next I dream the love is made of glass,

glass coming through the telephone

that is breaking slowly,

day by day, into my ear.

Imagery, not sentimentality, powered Sexton's verse. Sadly, too many writers merely picked up the confessional poets' autobiographical approach and ran with it. Adding to the problem was the counter-cultural movement of the '60s and '70s, and the birth of identity politics, within which each and every marginalized soul had something special to contribute to the world of poetry.

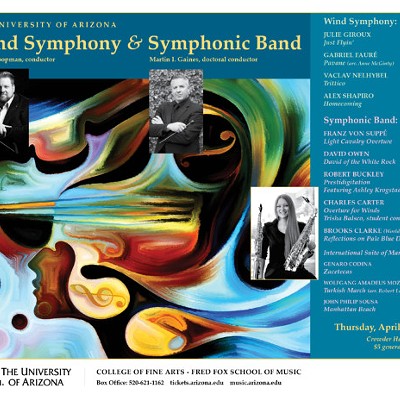

Acclaimed mystery writer and Tucson resident J.A. Jance was apparently one of these souls. Married for more than 10 years to an alcoholic who eventually drank himself to death, Jance is now a best-selling author. This summer, the University of Arizona Libraries, in conjunction with the Women Mystery Writers Archive, has reprinted Jance's literary debut, a poetry chapbook called After the Fire that was originally brought out in 1984 by a now-defunct Seattle-area small press, Lance Publications. Jance and UAL smartly opted to annotate these small, succinct poems so as to shed more light on a woman's dark struggle to survive an abusive marriage. Indeed, the annotations are more interesting, informative and, yes, lyrical than the poems themselves.

A good example of this is "Morning," which addresses the futility of a woman's housework:

This is the time when, according to the media,

She is supposed to settle back and relax

Over a cigarette and a second cup of coffee,

Receiving much deserved rest after bundling

Children and husband off to school and office.

What is Madison Avenue cannot know

Is how bleak and empty

The day stretches out through

The steam of that second cup of coffee,

Filled with mindless tasks,

Endlessly repeated.

Is that all?

Now, compare this with a similarly themed poem by Sexton called "Housewife":

Some women marry houses

It's another kind of skin; it has a heart,

a mouth, a liver and bowel movements.

The walls are permanent and pink.

See how she sits on her knees all day,

faithfully washing herself down.

Men enter by force, drawn back like Jonah

into their fleshy mothers.

A woman is her mother.

That's the main thing.

It's dishonest to compare anyone with Sexton, of course. But whereas the former poem is mired down by stale lines ripped from the pages of a women's lib mag, the latter bristles with imagery, metaphor and even a biblical reference. These seem mostly absent from many of the poems in After the Fire.

Poetry isn't a competition. Though Fire fails as a fully realized work, it succeeds as a testament to Jance's endurance as a human being and a writer. After all, survival poetry is about just that: survival. As long as Fire continues to give women the strength to escape their abusive relationships, then I say open the floodgates of mediocre verse. Still, don't let Jance quit her day job!