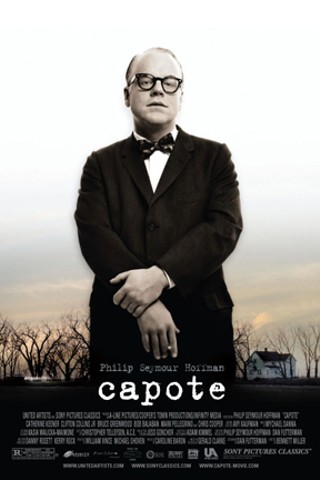

So it's doubly amazing that Philip Seymour Hoffman manages to pull off a performance as Capote that includes every superficial effect and affect that made Capote Capote, without somehow becoming a two-dimensional cartoon character.

Hoffman does indeed do a pitch-perfect impression of Capote's powerfully homosexual drawl and weirdly idiosyncratic movements, and yet he seems like a real person, someone who's deeply flawed and riven with vicious emotional turmoil. It's hard to say that this is the best performance of Hoffman's career, since he's been so brilliant in the past (see especially, please, Love Liza and Owning Mahowny), but it's certainly up there with his best work, and is therefore one of the best performances you'll see during the next tera-century.

He's ably aided by the fine script by Dan Futterman, who, strangely, has never written any other film. Futterman works from the Capote bio by Gerald Clarke, but leaves out pretty much everything except the years in which Capote was writing In Cold Blood. This allows for an intensity of focus on Capote's weird narcissism and his struggles with and against his own tendency to empathy. As Capote writes a book about two cold-blooded killers, he can't help befriending them. And yet, as they face execution, he's only capable of thinking about his own failings and needs. While this odd story, well-known to anyone who's at all familiar with Capote's life, grants him a character that is almost perfectly dramatic, it's also necessary that he seem real as well. Futterman's dialogue does this without making the mistake of having him talk like an ordinary human being.

And of course, Capote was no ordinary human being. By his own estimation, he was one of the most important writers of the 20th century. He probably wasn't far off in this guess, which sets him apart from most self-professed geniuses. And he hung around people who were more than able to keep up with him, but knew enough not to, including, notably, his best friend, Nelle Harper Lee, (better known as Harper Lee, author of To Kill a Mockingbird) and his boyfriend, Jack Dunphy (who unfortunately remains almost completely unknown for his own weirdly dark writing and thus gets a place in history as "that guy we saw Truman with.")

Bruce Greenwood, who's been flying below the radar in character roles for the last 25 years (who can forget him as "Guardsman Number 5" in Rambo: First Blood?) is potent but subdued in this role. You can feel him burn with a jealousy that the written script wouldn't even hint at, and when he's on the screen, he almost manages to steal the focus away from Hoffman. Seriously: Someone should throw an Oscar at this guy, because he did exactly the kind of performance that never gets noticed but really defines "supporting actor." He produces, by his stance, gaze and intensity, a quiet but volatile atmosphere that accents and underlines the showier stars around him.

Also turning up the thespian dial to 11 is Catherine Keener, who's always good, but here finds herself in the nearly impossible position of sharing the scene with Hoffman. When Hoffman is on the screen, even wide-angle landscape shots feel like close-ups on his complicated expressions. Keener, like Greenwood, doesn't compete but does provide a necessary counterpoint: Her expressions show that she doesn't take Capote's self-importance seriously, and without her subtle head-shaking, this movie would fail to make the comment that it strives so hard to make.

With so much in its favor, Capote is still not the movie it should have been. It's certainly excellent, but first-time fiction/feature director Bennett Miller (he has one documentary to his credit) makes a number of obvious freshman mistakes. He's too in love with the beauty of his black-and-white cinematography, too engrossed in long pauses that do nothing but accent how filmy this film is, and too tied to the entirety of his work, failing to whittle down the unnecessary moments so as to make a more concise, and thus effective, film.

Still, these failings are minor in light of everything else Capote has going for it, and cinematographer Adam Kimmel's imagery is beautiful enough to account for Miller's fascination with it. Plus, Miller deftly handles the film's loudest unspoken theme: the way in which a flamboyantly and unabashedly gay man could openly work in the conservative center of the country for an extended period of time. It's a fascinating portrait of what it was to be gay when the word was nearly unspeakable, and it plays out strangely in the face of the open racism that Capote saw and even indulged in.