"I'm sorry; I have to take this," he tells me.

He talks into the phone. "Yes, that one is available. Yes, $800. OK, call me back."

It's his assistant, calling from Derks' metal-works studio near downtown, Derks explains.

Derks then continues walking with me down a dirt path at Damian Ranch--a former girls' school that had a brief life as a hippie commune in the 1970s, off Swan Road north of the Rillito River. Now it's a residential community mostly consisting of artists and writers, their homes hidden in clusters of mesquite trees and cactus. Derks has lived there with his daughter on and off for 17 years.

They share a modest two-bedroom house, and down the path is a small building that serves as Derks' home studio, where he usually paints. It's his family's bit of desert paradise that he's earned by making art for 22 years.

Derks admits he has the kind of life most aspiring artists would sell their souls to live. He's been making art full-time, never needing to take a job waiting tables or working in an office.

That's not to say life has always been easy. When Derks' daughter was 2, his relationship with her mother fell apart, and they divorced.

"It was a time that was full of so much chaos," Derks recalls.

He received full custody of his daughter, and wondered if he could continue making a living as an artist.

Derks was largely creating metal sculptures with found objects and scrap metal, and was gaining a following at the time, with his work on display in several galleries--but taking on single-parent duties was a big step. Nonetheless, he continued. He's always been able to pay his bills, and more importantly, provide his family with a good home, a safe car and health insurance.

"Sure, it would be great to have been in the Met (the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City), but that's not what life ended up being for me. But still, I've been lucky to have a career."

However, he stresses: "It's without a safety net."

At the beginning of the year, gallery sales of his work began to decline. With his daughter starting college next year, he wondered if there was some way to keep this national economic crisis at bay.

"I pushed forward when I became a single dad, just like I'm doing now, because I had no choice. ... We live simply. I even shop for my clothes at thrift stores," Derks says, smiling wide and pointing to his short-sleeve, button-down cotton shirt.

Then the cell phone rings again, and Derks checks to see who is calling. He looks up as if to say, "Sorry."

"Hi," he says. "Oh, that's great."

He hangs up, and he lets out a small sigh.

"That was a sale. That's good," he says, as if it's one more thing he can cross off his to-do list.

Thanks to the current economy, we're in a new world for Derks and others who produce art to make a living.

"I'm an old dog who needed to learn some new tricks," he jokes.

To learn those new tricks, Derks, 51, joined two up-and-coming artists to form the Tucson Revivalists Artists Collective, aka TRAC. Since forming in February, they've brought in about eight other artists, with the goal of helping each other ride out this changing economy by learning how to better market their work, often using tools that younger artists have a better handle on, like social-networking sites.

The group is now holding its second show at a building owned by Derks, at Main Avenue and Third Street, that he's turned into Gallery 801 (artinarizona.com). Behind the gallery is a metal-works space he uses for his sculptures and also subleases to two other artists, and behind that is his gold mine: his own personal scrap heap of rusted metal, discarded instruments and other odds and ends that could one day make it into Derks' pieces.

Running a gallery and hosting shows is new territory for Derks, but it's important territory for him to cover: He came to the conclusion that he needed to become less dependent on the eight galleries he works with. Derks decided he could make up for a loss in gallery revenue by self-marketing to locals. He then needed to get down to the nitty-gritty of running a business.

"I started to discount what I had on the floor," he says. "It's what any retailer would do to move merchandise."

Derks says TRAC has provided him with a way to connect with other artists, even from mediums and styles different than his own. It started with Derks turning to a tool he's been previously slow to embrace: the Internet. He put an ad on Craigslist looking for artists interested in meeting to address the economy and to trade marketing tips.

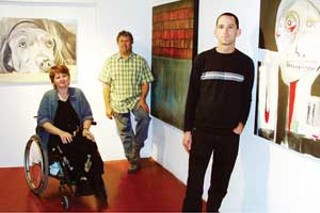

Two artists responded to Derks' message--Carolyn Stanley Anderson and Bryan Crow--and the three formed TRAC.

This is a crew that, on the surface, looks like they have little in common, at least when it comes to their art. Anderson's work focuses on dogs: She creates canvases large and small with portraits of man's best friend looking back with deep, soulful eyes. Crow, like Derks, does some metal sculpture, but primarily focuses on large paintings that sometimes resemble a mishmash of Picasso, Matisse and Pollock.

But Derks says the three actually have a lot in common, starting with the fact that they all use art to express perseverance through hardship. Derks survived the end of his relationship and became a stronger presence for his daughter. Anderson, 35, lived through an SUV rollover accident at 17 that left her paralyzed from the waist down. Crow's art has helped him stay clean and sober for the past eight years.

Through this thread, they've developed a friendship and--with other artists--a community. Derks says Anderson has taught him the joys of social networking on Facebook. Derks also put up a Web site featuring his work, and sat down with Crow to help him do the same. These are examples of the kind of assistance they want to offer each other through TRAC.

There's also an element of giving back: The group wants to help local charities. During their first show, they raised money for Beads of Courage (beadsofcourage.net), an art-therapy program that works with kids with major illnesses who undergo numerous hospital treatments. The first show's online auction raised $1,700. During this second show, which runs through April 16, the group is continuing to sell beads for Beads of Courage and is planning to do a benefit for Temple Emanu-El.

For Anderson and Crow, they like the idea of giving back to the community. Derks agrees--and also understands that what goes around, comes around.

"Some artists actually don't like the idea of giving away their work. In an auction, a piece never sells for what it is really worth. That is true, but I remember the first piece I donated. It sold for $300, but I can trace $30,000 worth of sales back to that auction," he recalls.

For Derks, TRAC is all about teaching him new ways of doing things, or, as he puts it, "to avoid traditional ways of doing things."

He explains: "I still produce specific work for galleries, but this economy has forced me to look at things differently. The one benefit is that it has given me permission to do work that I want to make, not just work for collectors."

The economy is certainly hitting artists in the pocketbooks--and hitting them hard.

For example, Sotheby's reported late last year that a sale of Impressionist and Modern paintings came in more than $100 million below the auction house's low estimate. In larger markets, like San Francisco and New York, gallery owners are reportedly cutting costs and fretting about keeping artists.

On the local gallery front, there have been closures, too. The Grogan Gallery of Fine Art closed earlier this year. The Tangerine Gallery, which has only been open for about two years, is in the process of closing, as is Illusions Gallery on the eastside.

Artist Miles Conrad, co-owner and director of the Conrad Wilde Gallery on Fourth Avenue, says his gallery is not cutting artists, although he understands why some artists may be worried.

"Artists must be feeling nervous right now. Some may be thinking, 'I'm going to get the ax,' depending on what gallery they are with," he says. "We haven't put any pressure on our artists. If the work is good, it's good. That has nothing to do with sales."

Some artists complain that galleries limit them from experimenting with new styles or mediums. However, Conrad says he and his partner have taken a different approach.

"We've had conversations with our artists that, 'Look, if it's going to be slow right now, maybe this is the time to take risks.' Because I feel it would benefit us, too," he says.

And, yes, business has been slow. Conrad says sales started to decrease in the fall, although they've rebounded a bit this spring. The gallery also offers classes and sells art supplies, which have minimized the problems that come with a recession. He also thinks his gallery's wide appeal has helped.

"We're positioned in such a way that our artwork tends to be more accessible. We have wealthy collectors, and we have medium-income collectors. That is one of our strengths, that we are more reasonably priced to begin with," Conrad says.

Down the road from Conrad Wilde on Sixth Street is the Davis Dominguez Gallery, owned by Mike Dominguez and his wife, Candice Davis. It's considered one of Tucson's most established high-end galleries; however, Dominguez says they have felt the effects of the recession. As a result, he and Davis have had to be more careful about costs. For example, they no longer buy print advertising, although they continue to do direct mail to announce new shows.

And they have a rule.

"If we both don't agree, then we don't do it," Dominguez says.

"We're not recession proof," he admits, "so we've changed employee schedules and cut spending. But we still have 35 artists. We still change our exhibits every six weeks. We are still well-staffed. That isn't going to change."

Dominguez says--just like at Conrad Wilde--that sales in the fall were down, but have picked up in the spring. The decrease, however, didn't throw them off too much; after all, they've owned the gallery since 1976.

"This isn't our first recession," Dominguez says. "We are in a great location and have great artists. As far as we're concerned, we are poised for the recovery."

While Derks and his fellow Tucson Revivalists Arts Collective members also want to be poised for the recovery, they first need to ride out this economy. In other words, they're looking for bigger results during this slowdown and after it, too. Anderson says that's what the word "revivalists" is all about.

"When we first sat around talking about what we wanted to do with TRAC, we thought about the WPA (Works Progress Administration) and the Great Depression and all of the tremendous artwork that came out during that period," Anderson says. "That's what we'd like to see happen in Tucson. We could sit around and complain that the economy is going to ruin us, or we can get busy creating good work and making people find joy in art."

Anderson, who lives with her husband and two young children, says that's what she's discovered in her own art: a sense of joy.

Because of the accident that left her paralyzed, she and her husband were advised that Anderson would probably not be able to carry a child to term--and they wanted children.

Anderson is a woman who says she spent two years feeling sorry for herself before she let loose. Since then, she's gone to college, worked and gotten married, often changing people's perceptions of what a woman in a wheelchair can and is supposed to do.

During her first pregnancy, Anderson was confined to bed rest by her doctor. Her constant company was her service dog, Tyler, a black Labrador she trained to retrieve keys and even laundry from the dryer, thanks to help from Handi-Dogs, a local service-dog-training nonprofit.

During bed rest, she decided to paint, using Tyler as her model. Friends responded overwhelmingly; some asked her to do portraits of their dogs. By word of mouth, she began doing other commissioned works.

"I continued with dogs when I started to paint again, because I realized I didn't want to paint negative images. This is what I wanted to do around my children. I wanted it to be positive and life-affirming."

Anderson says she also paints for another reason: It's healing.

"When I get to the point that I get to make a living from it, like Steven, that's great, but I'm not there yet," Anderson says.

That's not to say her art hasn't helped her cash flow. The Internet has proven to be a good marketing tool, especially sites like Etsy.com. The same week her dishwasher broke, Anderson says, she sold a print to an Etsy customer in Canada; other orders from Canada have followed since.

"Canada has been good to me," she jokes.

She's also been able to barter her art, most recently for a large dog crate, needed for the newest addition to her family: Loki, a Weimaraner. Tyler passed away last year, and Anderson plans to train Loki to retrieve items, too. For now, he's busy causing mischief with her kids.

The trades--she also received a KitchenAid mixer through bartering--the sales and the recognition are important to Anderson, who refuses to think of herself as a victim, she says.

"Once I went down that path, everything got so much better, and my world opened. It continues to open," Anderson says.

Bryan Crow also used art to heal. He spent some time in Tucson when he was homeless and using drugs as a young man, and he moved back after he got clean; he wanted a fresh start, and remembered Tucson as a generous and kind place.

Crow moved in with an artist friend who taught him basic welding; together, the friends would walk near the railroad tracks at night to find metal scraps. Eventually, Crow got a job--and had lots of free time sitting at a local treatment facility's security desk.

"I started drawing, and soon, I brought paints with me to work, and I've been painting ever since," Crow says.

Crow is now married with a 6-year-old son. His goal is to earn half of his income through his art; he recently returned to school to learn graphic and Web design. He takes his son to school in the morning and then works in his home studio before picking up his son from school.

"I feel I have to do this work. This is survival," he says.

Comfort has come through TRAC; he says the camaraderie between himself, Anderson and Derks, as well as the other artists now involved, has become important to him: He savors having that regular contact with other artists who share the same objectives.

"We're not out there surviving on our own," he says. "The economy has put people in a state of fear. I understand that. But I think that art can offer people an opportunity to expand their life, joy and happiness.

"I'm not trying to save the world," Crow says. "But I think art can."

For More Information

• Call Steven Derks at 370-1610 to find out more about the Tucson Revivalist Artists Collective (TRAC).• The current TRAC show is at Gallery 801, 801 N. Main Ave., and features the work of founders Derks (stevenderks.com), Carolyn Stanley Anderson (muttbutt.com) and Bryan Crow (bryancrowartist.com), as well as members Dana Smith, Lee Beach, Rebecca Thompson, Karen Dombrowski-Sobel and Peter Eisner. It also features the work of Dan Lehman, Don Gerard, Cody Robertson, Debra Houghton and Ian Houghton. For additional info, visit artinarizona.com.

• "Natural Wonders: Three Regional Artists Interpret the West," paintings by Duncan Martin and Debra Salopeki, and bronzes by Mark Rossi, is currently on display at the Davis Dominguez Gallery at 154 E. Sixth St. For more information, call 629-9759, or visit the gallery Web site.

• Conrad Wilde Gallery's current show, the Fourth Annual Encaustic Invitational, with 20 local and national artists, runs through March 28 at 210 N. Fourth Ave. For more information, call 622-8997, or visit the gallery Web site.