Two assistant professors from the University of Arizona's College of Education believe the obstacles Native students face have to do with the values, experiences and languages they are exposed to in the classroom.

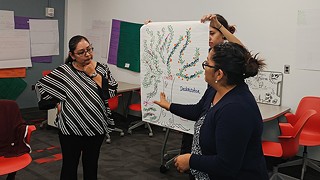

The professors, Jeremy Garcia and Valerie Shirley, had numerous conversations with Indigenous leaders across Arizona. Various tribal communities were at the table to discuss the state of education. "Since we organized that meeting, that was the birth of this movement to generate the Indigenous Teacher Education Project," Shirley said.

ITEP is an Indigenous education component within the University of Arizona's elementary education program. Founded in 2016, Garcia and Shirley designed the project to provide professional support to Native American preservice teachers by training them how to serve Indigenous communities in the field.

The two-year program began in the fall of 2017 and is about to finish up in the spring of this school year. There are 14 preservice teachers enrolled who come from four Indigenous communities: two Pascua Yaqui, four Hopi, one Tohono O'odham and six Diné (also known as Navajo).

Hannah Evanishyn is a Diné preservice teacher in the program. She said Garcia and Shirley's foundational courses helped garnish her understanding of how colonization has impacted Native education over time.

"Reclaiming education is a way of decolonizing," she said. "It is also something that requires critical thought and reflection." In their course called "Indigenizing Pedagogies" Garcia and Shirley give their student teachers a lens to contextualize Indigenous education.

"The first [session] is really taking a look at the history of American Indian education," Garcia said. "So you're looking at the era of issues around boarding schools, also looking at language revitalization."

In the late 19th century, the U.S. government forced thousands of Native American children into boarding schools that effectively stripped them of their culture. The assimilation process included changing their names, cutting their hair, deciding what clothes they wore, what language they spoke, what skills they learned, what religion they practiced and what version of history they were taught. Two hundred years later, the loss of culture and history still persists. Indigenous communities are working to relearn and embrace what they lost.

"It's a pathway to examine how schooling systems have impacted Native communities historically and also in contemporary times," Garcia said. "But then also looking at the ways in which, as emerging teachers, they can develop curriculum that embodies their own tribal community goals and knowledge and values."

Through their grant with the U.S. Department of Education, ITEP has been able to partner with the Baboquivari Unified School District in Sells, Gila River Indian Community Schools and the Sacaton School District near Casa Grande, Tohono O'odham Community College, San Carlos Community College, Apache College and a few schools in the Tucson Unified School District that serve students from the Pascua Yaqui tribe. The teachers receive a range of experience in elementary and middle school grade levels.

The USDOE recently awarded ITEP another grant, now worth $1.2 million, to continue their work with another group of students, expand their courses and opportunities for preservice teachers and create partnerships with more local schools that serve Indigenous populations.

How can all schools better serve Indigenous students? Garcia said it's really a conversation about identity.

"I think there's always this concern about the ways schools can reinforce a student's identity or they can actually go against that in different ways," he said. "How do we provide a learning experience that values the ideas of math, science, literacy in ways that gives them access to higher education...while also including their cultural values and knowledge and lens?"

The Navajo Times reported that in 1980, 93 percent of Navajos spoke Diné. In 1990 that number declined to 84 percent, and in 2010, it dropped to 51 percent, according to Census data.

ITEP began with a summer full of courses provided by the American Indian Language Development Institute, which is also housed within the College of Education. The preservice teachers were given the experience of learning a Native language and methods for teaching it to young kids. This was possible through the use of visual aids, symbols and sign language.

Kristy Pavatea, one of the preservice teachers in the program, said ITEP was structured in a way that made her realize this was something all Indigenous children could benefit from. She came to Tucson from the Hopi-Tewa community in Polacca, Arizona and hopes to use her skills in graduate school and diverse Indigenous communities.

"This project really allowed me a safe place to unpack personally, to really understand notions of my identity and my values, and a safe place where I could share proudly aspects of who I am as well, my culture, and my language," Pavatea said. "Respect was a key aspect instilled within the realms of this project."

While there is still lots of room to grow, Garcia and Shirley said they are confident in the direction of their project. They've gotten attention from other institutions with similar missions, asking them how they engage in this process of training Native teachers how to teach Native students.

Garcia and Shirley are looking at ways to make their program more sustainable so that it can become a permanent component within the College of Education. Since all the preservice teachers must also complete courses required for certification on top of the Indigenous education training, they are looking at ways to make the course load a more realistic and accessible thing to do.

The USDOE grant allowed them to begin the project, but grants are only short-term funding. The professors are in the process of creating a funding source within the UA Foundation, the university's nonprofit. They plan to open an account to receive donations from the public.

In their conversations with Arizona's tribal leaders, Garcia said they want to see a program that would help prepare the next generation to sustain and to lead their communities. They want the youth to understand the importance of sovereignty and nation-building.

"For tribal communities there's a unique sense of urgency and a sense of accountability to that," he said. "It's really speaking to the values that are coming from within the tribes themselves, whether that's entrepreneurship, whether that's economic development, whether that's culture and language preservation, whether that's protecting particular sacred sites—how is the next generation being prepared to understand their potential role in serving their community?"

"For these children are the key to the perseverance of our people, and this showcases to me the importance that lies within our work, and also the importance of up keeping this work," Pavatea said. "We have set a strong foundation but also have a long ways to go and I am more than anxious for this journey."

To learn more about the project or how to make a contribution, visit facebook.com/UAITEP/.