Both of Kroll's parents had refined tastes when it came to the arts, and they had a heavy social cachet. They exposed Kroll, the middle child, to art at a tender age. "My mother would drag us to every museum in New York," Kroll says. And his fascinations blended art with jazz and, when he hit his teens, porno. He'd sneak off to Manhattan to purchase girlie magazines and hide them in woods near his house. He'd also sneak off to see jazz in the city too, Coltrane and others.

"I was in the audience for Bill Evans when they recorded Sunday at the Vanguard," he says.

He harbored a serious interest in literature as well. "I saw Norman Mailer speak at Carnagie Hall and the first thing he said was 'Kick her in the cunt.' He said that over and over. I was 15 years old. [Gregory] Corso was there drinking from a flask. This was Carnagie Hall, so it was all about going against the rules of proper behavior."

Kroll's natural aesthetic sense, and overall appreciation of beauty, came from his dad, Boris Kroll, a self-taught hand weaver and designer internationally recognized as a visionary and manufacturer of colorful textiles and weave designs. Along with his reputation came millions of dollars, and the Manhattan-born Kroll grew up with a nanny ("She was huge to me") in a house on a hill overlooking 10 acres, located in the upscale, mansion-filled Westchester County in New York. His mother was a shoe model, a "trophy wife," Kroll says, who had a keen eye for beautiful things.

He got his first camera at 16, "a Pentax 35mm. It was a gift from my father's friend, Bob Lord. I knew I was getting something interesting from a very cool cat; he was one of my father's elegant friends."

His first picture "was this weird distorted picture of my sister underwater in her red, one-piece swimming suit" that later reminded of him photographer André Kertész and his distorted nudes.

And just as if he'd joined a band or became a gynecologist, the camera, Kroll figured out, was his way of getting closer to women.

He studied literature and comparative religion at Bard College but quit because, Kroll chuckles, "my dad didn't want me to continue there because I was smoking pot."

He was reacting against his own privileged world: "I was embarrassed to ride in that black continental. I just didn't get it. Diane Arbus and I resented the wealth we came from. She felt it impeded her closeness to the world. That wasn't my problem. My problem was I didn't understand why I had been born in to this privilege. I had a lot of empathy for the poor. She didn't seem to have any of that. And I saw how money made my dad miserable, and I wanted no part of the misery."

Kroll switched to cultural anthropology and graduated in 1969 from University of Colorado in Boulder. With $300 in his pocket, he headed for Woodstock, New York but managed instead to open the first-ever photo gallery in Taos, New Mexico, one specializing in artful partial nudes.

He soon got into photojournalism because "Vietnam had me upset. I thought being out in Taos making art when Vietnam was going down was a shitty thing to be doing."

A freelance assignment from Newsweek found him shooting New Mexico's counterculture communes. He was eating peyote and "got to hang with Dennis Hopper, and with his wife Michele Phillips and Dylan's manager Albert Grossman. I also learned early on how you get screwed financially in photography."

Kroll returned to New York working as a photojournalist. His travels resulted in Sex Objects, the photo-documentary book that focused on American sex workers. Its realism is shaded with compassions and sadnesses; Kroll observed and documented without judgment, and never valorized the tragedies or sad choices of the single women and mothers. It's a strange, timeless and elegiac reminder how just being human can even devastate people.

Some considered Sex Objects pornographic and because it was funded through a government grant, it was slammed on the front page of the New York Times by New York Republican Sen. John Marchi. Key figures in the art world came to Kroll's defense.

In 2014, Sex Objects was prestigiously cited in Martin Parr and Gerry Badger's The Photobook: A History Volume III as a genre-shaping photobook.

"Martin Parr, he is God," Kroll says. "You get into that book and you're solid for the rest of your life. Only wish my parents were alive to see that."

Good luck trying to find a copy of Sex Objects. It now fetches close to a grand online. He met Koli fashion model (and Oui magazine centerfold) Lynka Adams in 1976, married her 1980. She starred in his work, and they have two daughters, Willa and Leah. In the meantime he began teaching at local colleges, including The School of Visual Arts, Hunter College, and Antioch in Baltimore.

In 1986 he met Annie Sprinkle, who actually lived next to Kroll's Manhattan studio.

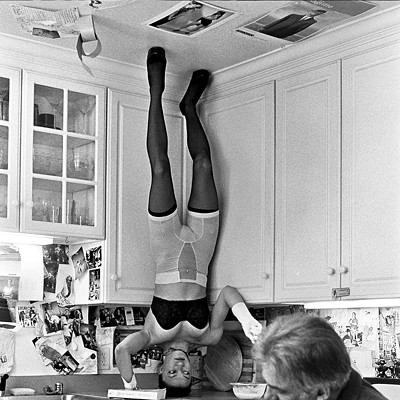

"Annie was important in my development as a photographer," Kroll says. She was hooked into the whole fetish scene. Rubber and leather? Killer. I loved how women looked in it."

Kroll says he photographed Lynka in an outfit Sprinkle had loaned him, including a cream-colored 1950's rocket-coned bra, and it had the look and feel of the stuff he'd hide out in the woods near his house as a teen. Those photos signaled Kroll's shift toward fetish.

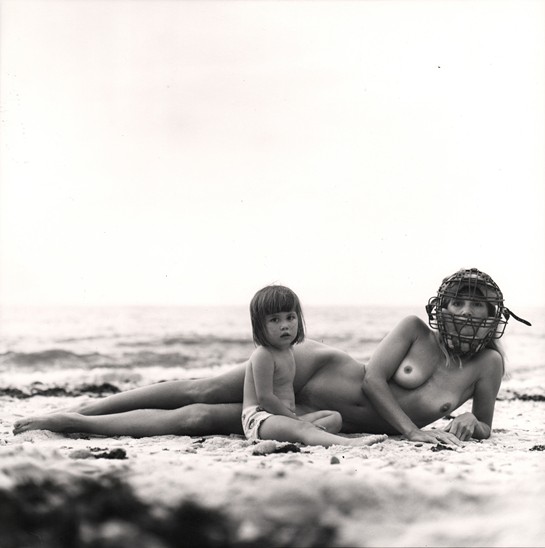

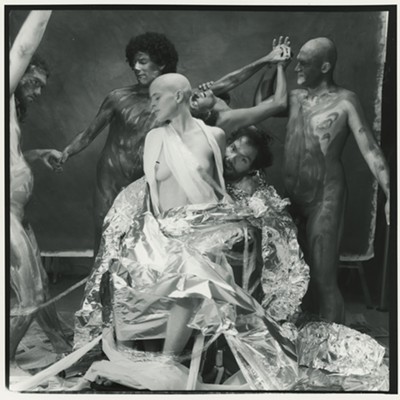

The family relocated to San Francisco in '94, and Kroll had begun working for Taschen books, a foremost publisher of art books (there are dedicated Taschen bookstores in various places around the world.) Taschen released Kroll photo books, including Fetish Girls, followed by Eric Kroll's Fetish Days (1996) and Eric Kroll's Beauty Parade (1997).

The books found Kroll exploring truths about his subjects and often expressing them symbolically; this isn't kink for sake of libido, and it's often hilarious. It's what Kroll continues to do now. He's always skewering something, even vaguely Freudian ideas of an artist depicting openly a world of fantastic fantasy, especially, say, a rubber-clad women wielding a strap-on penis in a moody shot filled of negative space. It's sometimes male versus female, matriarchal versus patriarchal, or female versus female, or point of view versus subject. Men are often just peripheral, like second-class citizens. (Kroll occasionally inserted himself into shots; we see a much younger Kroll on the floor sucking toes of one leather-clad woman or under the ass of another, each with a directionless gaze.) Women are mostly dominators and mostly worshipped; sometimes they're bent over, knotted up, suckled, or sitting on someone's face. Some they're suppressed, like a ball-gagged woman at the end of a leather tether—at the end or her rope, so to speak.

Kroll finds women who are exceptionally lovely in ways that aren't always traditionally defined—they can be considered overweight and zaftig and flawed, or classically beautiful—but they all exude extraordinary sexual tension, not just in countenances and curves, and the all the ribbons and bows of fetishistic leather and rubber apparel, but in auras, that sort of intangible something that makes viewers want to know more. Kroll's gift is sensing sexual tension and collecting it in his camera.

For Taschen, Kroll also shepherded and edited exquisite, spare-no-expense books on mid-century giants in fetish and bondage art Bill Ward and Eric Stanton, as well as photographers such as John Willie, Elmer Batters, Chas Ray Krider, and artist Natacha Merritt and others.

* * * *

Kroll split with his wife and in 1996 met Felice—28 years his junior—at Bondage A Go Go in San Francisco. Felice (she requested her last name not be used) became his live-in lover, his muse, his model, and a sort of big sister/surrogate mom to his two daughters. Kroll and Felice explored San Francisco's rich subterraneous worlds of fetish.

Kroll only gets emotional when he talks about his daughters. "You want the best, you do the best. You can never tell." He pauses. "Kids just want to be loved."

His daughter, Willa Kroll, is now 27 and teaches second grade New York City. She describes life with dad as a "nourishing time," and says he "encouraged her creativity." Willa says she was always aware of his fetish photography work, even though he kept no evidence of it around their San Francisco house.

"It's funny I guess because it was always around in San Francisco, because it's so much more open sexually. When I told my friends, especially the boys, what my dad did they all thought it was pretty cool. And then I got the shocked responses at my all-girl Catholic school.

"But listen, my father was so good at making me feel proud of my creative work. Always. And he'd do things like take pictures and show all his friends. It's why art is such an important part of my life, and in my teaching."

What does she think of dad's fetish work?

"I've never been ashamed of the work that he does. From my feminist studies in college, and my feminist beliefs, I've always been able to speak my mind. Having said that, I've purposely avoided studying closely his work, not because I think it's not art, it just not something I'm particularly interested in. I keep a safe distance from it so as not to confuse that with who my father is."

Kroll created a persona for Felice, calling her Gwen (after John Willie's character Sweet Gwendoline), and she appears in many different guises in Kroll's two-volume The Transformation of Gwen, released in the early 2000s. It's the most fervently sexual of anything Kroll has shot. In the postscript of the first volume he writes, "I think one of the reasons I photographed Gwen, my girlfriend, having sex with so many partners was to face my greatest fear—that my girlfriend would cheat on me. So I photographed it. I controlled it. It happened repeatedly, right in front of me. I could judge her reaction. I could record her response. I had visual proof. In the end it didn't make any difference. I knew there were moments when I'd see her kiss another man or run her fingers through a woman's hair and I'd feel myself get hard. There were moments when I'd see her do the same thing and I'd feel a sharp pain of regret and sense of loss."

Brandon Arnovick was one of few Kroll male models in San Francisco. He reckons he participated in between 50 and 75 "official" Kroll shoots, and with Felice.

"Felice is absolutely gorgeous," Arnovark says. "She was Kroll's muse and I was his prop. In my sex life I'm very average, missionary position, but I'm a little bit of sex-addict. I don't have pocket pussies, dildos and buttplugs and whips anymore. I have two children. But Kroll helped to liberate me."

What did he learn from Kroll?

"I'm short, uncircumcised; I'm not like some Adonis dude. He showed me that my package, by that I mean my whole being, wasn't a detriment at all. It was huge for me. And it was liberating, freeing. At first it was like, 'Who's this weird old man?' But he had good charisma, and he's charming, and he's smart, and he's fun as shit."

After eight years together Felice and Kroll called it quits.

"She was changing at her own accelerating rate, and I wasn't changing much," Kroll says. "Felice was my way out of my marriage too. I was really in love with her."

"I lost my sense of self," Felice tells me, adding, with a chuckle, that Kroll's "not the easiest man to deal with."

Kroll soon moved to Los Angeles, continued working, and edited for Taschen the highly regarded Neil Leifer: Ballet in the Dirt—The Golden Age of Baseball, a beautifully wrought photobook of baseball in the '60s and '70s.

When the big-paying gigs were drying up he moved to Tucson. In 2010 he edited Warhol: Dylan to Duchamp, a book published by the Eric Firestone gallery. It's a mind-boggling collection of Warhol shots highlighted by Bob Broder, an Arizona photographer who shot Warhol in Tucson in '68, working on his film Lonesome Cowboy.

And Felice is now helping Kroll organize his work, which in no mean feat, and she helps sell some of his collectables online, stuff he can part with. Other than Social Security, Kroll doesn't have much of an income. He's in debt. He doesn't shoot anything "just for the money." He pays models sometimes with rare pieces straight from his collection—I watched him pay one with rare Bettie Page prints.

His fetish and bondage collectables and collection—separate from his photography work—could likely fetch a million dollars or more, if parceled out. That doesn't interest Kroll one bit. He's not in it for the money. It's all emotional.

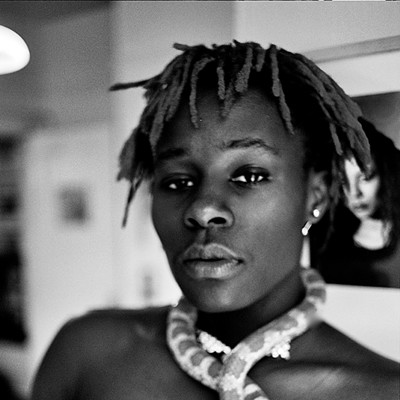

"A lot of people shun that which they don't understand," he says. "That's exactly what attracts me. Always has. I remember someone, I don't remember who, said his favorite kind of music is 'anything I haven't heard.' That's why I still drive 20-some-thousand miles down the road every year. That's why I approach the waiter, or the golf pro, or anyone I think has something that I want to record. I really like to find that which turns me on and put it in a photograph. It doesn't matter to me whether I'm going to shoot some absolutely sexual, sensual woman—which I really like doing—or anything else."

* * * *

Sammy M pulls up the tighty-whities she's been instructed to slip on, shoots a glance over her shoulder, pushes out her ass and asks, "Are these slutty enough?"

Her face sneers with tongue-in cheek delight, and she says, "It's the sexual tension that brings me here."

Kroll is stooped low, shooting Sammy, muttering instructions like: "Turn a little that way, stick your ass out ... Yes! Like that! Yes!" And, "Use this like a dildo! Yes!

We're out at Saguaro National Park east of Tucson, juxtaposed in the lovely desert, and the sun is waning. The park rangers haven't nosed around much. They passed through at a distance earlier and didn't stop; obviously they hadn't noticed the half-naked girl and vintage pieces of sexy garb hanging in the blue palo verde tree. Last time Kroll was out here shooting he got popped for doing "a commercial photo shoot" and had to pay a fine. But, as he'll tell you, he wasn't doing anything wrong, the little guerilla photo shoot was anything but commercial. He'd be making money if it were.

The curvy Sammy is a 22-year-old UA journalism student who grew up in a Christian Science household. She plays the harp and dances at TD's Showclub. She called Kroll on a tip from a friend wanting to do some photos. That's how it often happens with Kroll. Women just phone him up to fetishize for the camera. Other times he just stops women on the street. They often agree.

Sammy continues to move and pose in the wan light, casting appropriate fuck-me glances for Kroll's lens with the seasoned grace of a skilled dancer who knows how to objectify herself with whatever version of the male (or female's) idea of what sex should mean, and she can turn it up or down, hot or cold, depending on how she gauges it in the observer's mind. It's real skill. She translates a kind sexuality in a way that few can, whether she's aware of it or not, and Kroll sees that in her, which is why he loves shooting her. Sammy will go into Kroll's collection for whatever purpose—perhaps a new book, another gallery showing, some presentation down the road, at the very least a day's work in his oeuvre.

But out here in the desert there's little or no sexual tension and Kroll transmits zero creepiness.

It reminds me of what painter Marcus-Orlen said about how when she paints "things become objects and they lose their emotional power if you concentrate on them too long." She said that's what happens when Kroll shoots women, and she was right.

If there's any reason to feel objectified, Sammy doesn't show it, even as she switches in and out of vintage lingerie, cheeky-ass cutoffs, and Bridgett Bardot swimsuits and a McCarthy-era cowboy kitchen apron with matching gloves and a skillet.

Kroll directs her to her back, to bend her torso sideways, keeping her legs straight. A look of exasperation falls over her face.

"I'm not that flexible, c'mon!"

"It looks like you're riding a horse!"

Sammy laughs, "How majestic."

Kroll keeps the tempo fairly high and Sammy never appears bored, or concerned with her appearance. Kroll had earned her trust. He is, after all, an old pro.

A tourist drives through the little lunch area a good 30 yards away, spots Kroll in his miss-matched pastel socks and a scantily dressed young woman and quickly circles around and exits the area.

"The rangers will be in here in a minute," Kroll says.

We retreat deeper into the desert and Sammy is soon splayed out on a blanket between saguaros and mesquites.

Kroll points his Leica camera into her face. Says, "I don't want to be your sex object."

"Ha-ha, good one."

Then he's up, stepping back, shooting. Says, "Look at me you'd just come six times from masturbating."

"I would be very tired."

Then she translates a certain tension, a certain shade falls over her eyes, which prompts Kroll to shout, "That's it!"

"Now look back at me with shame."

She does, and it's doesn't look fake.

She's game and Kroll knows how far he can go. He always knows, just as he knows where the artistic ends and pornography begins. He's a master manipulator and it shows in the work, there is context and space and a strong sense of implied sexuality and tease and humor and juxtaposition. It's what Kroll was after. Sammy too, she says.

Then he stops shooting Sammy altogether and takes stock of the rich surroundings, the light sinking into the desert floor, stretching out the landscape of saguaro and blooming-yellow palo verde and prickly pear. Kroll begins to snap the terrain and doesn't stop, turning in different directions to the light on the desert, the cool evening colors of a strangely green world. He points off the shadows falling over the Rincon Mountain range to the east, to the agave at his feet, and says, "such interesting things always going on." These otherworldly formations, hard to decipher, hard to collect, and the best you can do is capture the moments. That is, if you're lucky.

To follow Eric Kroll's exploits, go to Ericdavidkroll.blogspot.com. Kroll's prints are available for viewing and purchase at the Etherton Gallery, 135 S. Sixth Ave., 624-7370.