Chuck had written for Aperture. How does a writer get an article in a photographer's magazine like Aperture? He'd never admit this, but I think Chuck was a closet photographer. He thought visually, so it was a natural transition. I think visually, and I don't necessarily have to take pictures—I can just see it sometimes. And in a writer, that ability gives him an extra leg up on everybody else. Because he is so good at observing, he's not only seeing the obvious—the patterns and the visual compositions out there, but he's also sensing the feeling of the subjects when there are people involved. Chuck was really careful about that. One time when I was talking to him about interviewing somebody, we both mentioned about how our tallness could intimidate people. And Chuck said, "I'll tell you a secret. Whenever I'm interviewing a little old lady, I always make sure that I'm sitting lower than she is, and I talk very softly." He would always be very cognizant of the situation and try to find the best way to be the observer, the fly on the wall, even though he was gangly and tall.

Chuck and I both played well with others and have an ability to mingle with a wide strata of people, economic and intellectual. Chuck was intellectual, and I'm funny. I can be endearing, and I try to charm people. Chuck charmed people in a different way. My wife, Margaret, would say that it's because we both were the youngest in our families. We both could put people at ease, and that's always good. Somebody once told me that they thought that Chuck came from a lot of money because he had this sort of entitled feeling. He didn't come from money, but that's how they perceived him. And, they said he had no fear.

I'm amazed when I hear stuff like this. What are you going to be afraid of? What could they do to you? Chuck failed at times and quit jobs. It may be difficult for people who have never quit jobs or been fired to see how they could make it. I don't understand that lack of confidence, and Chuck was not encumbered by that at all—he was very confident in his own abilities.

And he was always ready and able to carry on a conversation. I just loved it when he lectured me on photography. I got a kick out of it. One time I had to say, "Look, you really don't know what you're talking about." He understood the visual concepts, but he tripped over the technical parts. Yet, he never let that get in his way of delivering a good sermon: "You people need to know this!" And when he preceded it with "you people," you knew you were in trouble.

I don't know if his memory was photographic, but he certainly had one of those garbage-can minds—whatever goes in, stays in. And he liked to mentally joust with people. He was like a gunfighter saying, "Ya' feel lucky, kid?"

Sometimes he'd ask people, "Oh, have you read this book or that book?" But he was the real deal, because he had read them. I think what made Chuck so good was his background research. Probably the number one failing among journalists today is that they just read a press release and write the story, instead of questioning things. Chuck questioned everything. Not only questioned it, but knew the background and where to find the rest of the story. Which other reporter would have known that some friar in Baja wrote about Indians picking seeds out of their excrement and eating them? Chuck did, and he wrote about this.

Chuck had a deep, deep appreciation of knowledge. Once I went over to his house and he was reading E. O. Wilson's book on ants. He acted like he had found nirvana. He said, "Can you believe this?! That this guy is this nutty about ants?!" Wilson is now famous, but Chuck knew about him a long time ago. Chuck was very eclectic, sort of like a black hole for information, from the carrier pigeon's demise to the geology of the Grand Canyon, and he sucked it all in. His reading list was off the charts in diversity. He not only swallowed what he read, but he could regurgitate passages at will.

My initial respect for him was as a journalist and his basics: tell the truth and confirm. But that, combined with his sense of seeing, made him extraordinary. I don't know any other writers who saw as well as he did, and as clearly.

In May 2010, I was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and was told I needed a double lung transplant and double heart bypass. Without surgery, in 2014 I was dying, so I tried to reach Chuck to write my obituary. A friend found him, and within ten minutes Chuck e-mailed me.

Jack

i talked to bill. consider it done if need be—i just got a new box of crayons. Your apparently too lazy to answer your cell phone.

now lay off that whiskey and let that cocaine go.

oh, and in minnesota i recommend the walleyed pike considering bleak, lake woebegone local fare. for god's sake dodge the lutefisk.

Chuck

Then a few days later, as I lay in the intensive care unit listening to a specialist describe the operation procedure, Chuck walked in, surprising me and astounding the staff. I don't remember much of his visit or what the doctor told me, but sometime after midnight three weeks later I texted Chuck on my phone and gave him a detailed update on my condition.

Chuck replied around sunrise,

Jack

i understand. sorry about the mask and glove moment—the staff who led me to the door said nothing and i managed to miss the billboard sign. and what the hell, since you have to bother with this you might as well be the first double double and get in the Guinness book of records.

i don't know anything about transplants but i do know that given such invasive chopping on you there will be a sense of depression to battle. being caged in Phoenix in the summer is probably better than being outside. on the way back from Los Angeles i came by again but your ward was having a moment of solitude it seems with no visiting. so i went over to the Heard Museum to see a friend. the people there wandering the courtyard in the summer blaze had all the zip of zombies.

given my little jaunts into the world, i notice there is not a lot of fair out there. so i am glad you caught a break. and of course St. Joseph seems to be the place for such treatment. i suspect the therapy will become addictive for you because you will finally feel that major American drug, a sense of progress, the same sensation as when training for a marathon where week by week one savors glimmers of change.

i'll be in and out of Phoenix and check in with you if that is possible. i'm down nogales at the moment where they are warehousing a thousand or so kids from Central America. they're not likely to have a St. Joe's as option in their lives. We do which is a piece of luck for us.

as Johnny Cash advises lay off the whiskey and let the cocaine go. You caught a break. And all the canyons will be there when you trot out of the medical caves.as Randy Newman, our national poet laureate, explained:

In America you'll get food to eat

Won't have to run through the jungle

And scuff up your feet

You'll just sing about Jesus and drink wine all day

It's great to be an American

Chuck

That was my friend Chuck. I survived my surgery, but two and a half months later he died of a heart attack.

Photographer Jack Dykinga was born in Chicago, where he also earned a Pulitzer Prize for feature photography. He has written numerous books, including A Photographer's Life and, with Charles Bowden, The Sonoran Desert and Stone Canyons of the Colorado Plateau. He is a cofounder of the League of Conservation Photographers. Used with permission from the University of Texas Press, © 2019

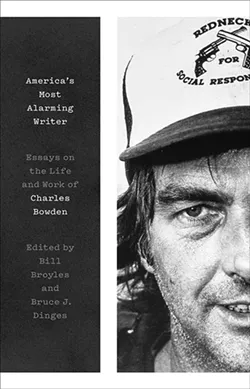

Excerpted from America's Most Alarming Writer: Essays on the Life and Work of Charles Bowden, edited by Bill Broyles and Bruce J. Dinges