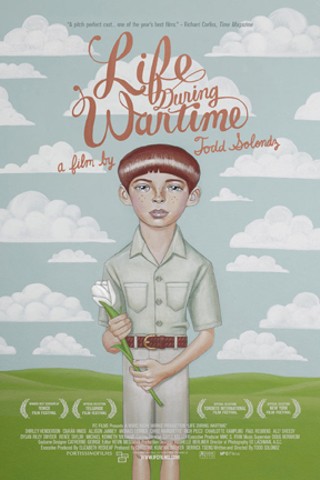

Life During Wartime is more of the same from director Todd Solondz, who emerged in the mid-1990s with the shocking Welcome to the Dollhouse.

Dollhouse is Solondz' most notable and most streamlined film, but it might also be his least personal. Since Dollhouse, the New Jersey-born writer and director has focused on experimental ensemble dramas that usually have something to do with the blowback of immorality: In Happiness, the primary pink elephant in the room is pedophilia. Tumultuous though it is, Happiness is a fairly strong film, with Solondz' screenwriting in full flower. Storytelling is less satisfying across the board, and self-degradation is the flavor of the day. Palindromes is a slight return to form and tackles a less taboo topic—although teen pregnancy is still pretty controversial.

In Life During Wartime, pedophilia is thrust back out of the shadows, but Solondz doesn't uncover a new way to discuss it. As with all of Solondz' work, the impression is made not by acts seen on screen, but through frank dialogue, and there's very little out of bounds in this film.

Trish (Allison Janney) returns home from a date with Harvey (Michael Lerner). Her ex-husband has long been locked away—for, you guessed it, being a pedophile—and Harvey is the first man to make Trish feel alive in years. "When he touched me," she recounts, "I got wet." It's probably not the sort of detail her 12-year-old son needs to hear, and that's the essence of Solondz: Challenge existing social mores, and wait for the reaction.

This story—focusing on the quick courtship of a divorcee who has finally gained someone's attention, and her precocious son, who lives in constant fear that he might grow up to be like his father—runs parallel to a more fragmented and less interesting look at an interracial couple at a crossroads: Joy (Shirley Henderson) leaves Allen (Michael K. Williams) after an anniversary dinner gone wrong. He is clearly trying to put a very troubled past behind him. She, it could be argued, puts herself in this sort of position more often than she should by working with addicts and felons attempting to piece their lives together. That's what has happened here, and Allen is in worse shape than Joy wants to believe.

There are points of intersection between the two plots—characters cross over from one story to the next—but ultimately, it's a shallow attempt at universality. The notion might be that every family or every group of friends has similar dark hallways in their houses, and maybe to a small degree, that's true. However, with this film, the stronger of the two narratives grinds to a halt, because it has to share time with a less interesting story with unappealing characters. Still, it's better than the anthology format Solondz has used in the past.

Solondz's return to the topic of pedophilia is curious, since there have to be other delicate issues Solondz hasn't investigated. He is one of the only filmmakers willing to create a legacy, such as it is, by using such a hot-button issue, but to return to the well here doesn't really add anything to the experience if you've seen Happiness.

The treatment of the subject in Happiness is an absolute wrecking ball, with Dylan Baker's unforgettable, brave and possibly pigeonholing performance as a man sexually attracted to his pre-teen son's friends. Some of those pieces return in Life During Wartime, just to make the story more uncomfortable: the boy questioning something he'd be better off not knowing about; the familial connection to the whole sordid mess; and, eventually, the leering father (Ciarán Hinds), out of prison and recognizing the monster within, hoping he can fight his urges.

The real trouble with Life During Wartime is not its subject matter; it's that the subject matter has been done more effectively by this filmmaker, and that such salacious material ought to have a certain amount of depth beyond its introduction. Here, Solondz doesn't build the concept to much of a crescendo, and the conclusion he does provide doesn't make the journey worth the effort.

Not that he should follow the buddy-cop direction taken by Kevin Smith (another indie darling of the 1990s who can't shoot straight these days), but Solondz could use a change of scenery. Certainly, pedophilia creeping into two of his four most recent movies verges on overkill.

As it stands, it's quite possible that the vast majority of the people who see Life During Wartime are only doing so because they already saw Happiness. And when filmmakers like Solondz start repeating themselves like this, they begin to lose the small, less-than-mainstream audience that their provocative stories draw in the first place.