Equal parts post-WW II art project and FCC-regulated television, this brand-new TV studio on west Drachman is a living thing, abuzz on the adrenalin of innovation and new technology. Experts hired from big cities help direct the bustling if uncertain young staff. Place smells of fresh paint, burning vacuum tubes and cigarettes.

Virginia Mittendorf, the station manager's wife, calms LaVerne and walks her to a mirror to demonstrate TV makeup application. Soon, cameraman Howard Smith is instructing LaVerne to look at the one camera whose light glows on top. He'll point each time it switches to the other.

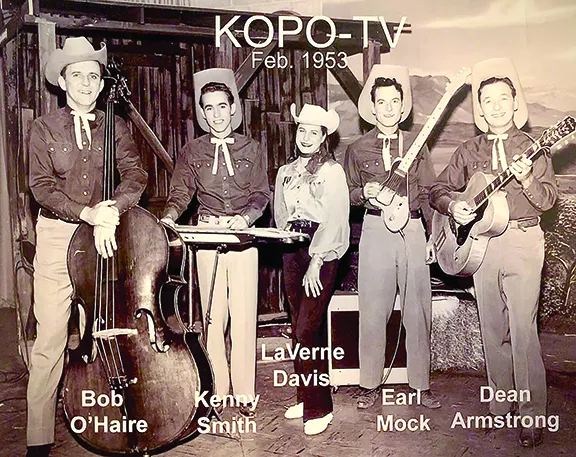

When she steps into the studio stage light she is beside future Tucson music legend, singer-guitarist Dean Armstrong and his band, the Arizona Dance Hands, which includes teen pedal-steel player Kenny Smith, bassist Earl Mock and drummer Bob O'Haire, all bedecked in burnished cowboy shirts and black string bowties like those favored by Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.

Lights flash and "Lucky" Channel 13, KOPO-TV (later changed to KOLD) debuts on the thirteenth second of the thirteenth minute of the thirteenth hour of the thirteenth day of the year, 1953.

Two cameras dolly slowly around Dean and his band, in front of LaVerne, sideways and up, experimental angles all—the kind of live TV proscribed years ago. Closeups of her fingers, hands and guitar, her face and back-tilted cowboy hat. A young Kitty Wells ready for her close up, changing life in Tucson living rooms forever.

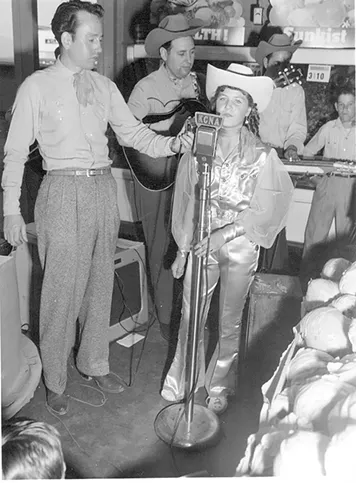

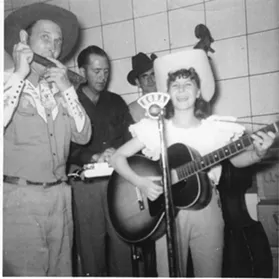

LaVerne might be nervous but this is her thing, skills honed after already performing more than four years on nearly all of Tucson's five radio stations, and at Tucson store openings, schools, dances, rowdy nightclubs, large fundraisers, concession-stand rooftops at drive-ins, and in roadshows and rodeos, sometimes by herself with her acoustic guitar or sometimes backed by a trio or a full Western dance band and orchestra.

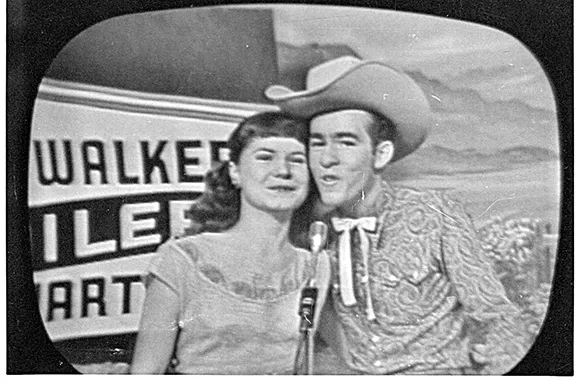

The country twang of "I Want to Be A Cowboy's Sweetheart" rises on young LaVerne's singsong croon, which curves up into a yodel. And like that, Tucson's Golden Age of Radio tumbles on a tune LaVerne learned from a Rosalie Allen 78 record.Singing cowboy Gene Autry owned the Tucson TV station then after killing it in Hollywood years before. (He also owned Phoenix's first station, KOOL-TV.) Dean Armstrong with Laverne become regulars on Channel 13, Friday and Saturdays, their fetching blend of pop, western swing and honkytonk.

(That cameraman, Howard Smith, was my father, a meticulous and shy radio-TV engineer, and a gifted musician and song arranger. Decades later he would share stories of Tucson's first days of live TV, the invention and the comedy, and talk of teenage LaVerne Davis, her singing. Said Laverne would "own" any song she sang, and at 14 was a TV natural. How it was a crime she didn't take off nationally. More than 40 years later my father and LaVerne, with her current husband Dave Lawrence, would start a band.)

* * *

Tucson in the late 1940s and early '50s was a glorified whistle-stop, but booming—its 1950 population of 45,000 would more than quadruple in the next 10 years, people mostly from smaller towns and rural areas moving in.

LaVerne saw Grand Ole Opry greats at Tucson Sports Center, including Lefty Frizzell, Maddox Brothers & Rose ("I learned their song "The Philadelphia Lawyer"), and many others. She would buy 78 records at Johnny Barker's Record Counter, inside McLellan's five-and-dime store (later Woolworths) on Congress in downtown. Marty Robbins signed a 78 for her there. She met hero Eddy Arnold at Tucson Gardens, and he signed a music book for her.

Most teen girls into music then were resigned to seeking autographs from grown men. Opportunities for Tucson musicians, particularly a female one, were about zero; angles had to be worked in New York City or Nashville or Los Angeles to hope to earn a wider audience. One had to travel to Phoenix to record in a proper studio. Tucson musicians began to suffer from a palpable inferiority complex, shame not easily overcome by passion. It lasted into the 1990s and gave rise to Tucson's idiosyncratic "desert" sound. Celebrated or not, Tucson-weaned greats sounded like the Old Pueblo—count the dozens, from LaVerne Davis to The Lewallen Brothers to Al Perry to Lenguas Largas.

Erstwhile DJ/record-company man/Arizona music authority John "Johnny D" Dixon puts it this way: "You had to leave the desert to find some success, and L.A. was close. Tucsonans Lalo Guerrero, Skip & Flip and Linda Ronstadt come to mind. In Phoenix it was Pete Jolly, Howard Roberts, Johnny & Oscar Moore, Art and Addison Farmer, Lee Hazlewood, Al Casey, Mike Condello, Alice Cooper, all moved to L.A. Waylon Jennings moved to Nashville, Buck Owens made Bakersfield his base. The Tubes moved to San Francisco. Leaving was part of life if you wanted to find national success as an entertainer in the '50s and '60s."

(Tucson-born Guerrero was something. Taught to embrace the "spirit of being Chicano," his Los Carlistas represented Arizona at the 1939 New York World's Fair. Linda Ronstadt remembers Guerrero serenading her when she was a girl. Guerrero hit paydirt in Los Angeles in the '40s. He acted in films, toured with an orchestra and opened a nightclub.)

A 1950 radio show on Tucson's KCNA (a station owned by Tobacco Road author and then-Tucson resident Erskine Caldwell) saw LaVerne appear with the sprightly, same-aged Molly Bee. Molly's dad soon moved the family to Hollywood where her star soared, on TV and in song, beginning with her 1952 hit version "I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus" and TV's "The Tennessee Ernie Ford Show." Molly was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

"She was a good performer, let me tell you," LaVerne says of Molly. "I loved her. She was a great yodeler too. I remember her hanging out with the Rat Pack in Las Vegas."

In 1956, LaVerne and future husband David were Amphitheater High School students. David played bass in The Rock-A-Billys, Tucson's first straight-up rock 'n' roll band, fronted by fellow Amphi student, Gary S. Paxton. (David's dad worked at Hughes Aircraft with Gary Paxton's father.)

Rock 'n' roll for teens was as innocent as it was still an artform. The Rock-A-Billys packed weekends at Tucson Gardens, from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m., slicing hours into 45-minute sets, repeating many songs. They'd fill the NCO club on the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. "The places were full of kids just dancing," David remembers. "There wasn't much else for kids in Tucson."

LaVerne wanted to sing rock 'n' roll and once tried The Rock-A-Billys, auditioning Paxton as much as he was her. Jealous of LaVerne's success, Paxton fired loud guitar riffs as she sang. He told her, "I play when I want, what I want."

"That's how Paxton was," David says, "only out for himself."

No audio recordings of the Rock-A-Billys exist. David saw little future in performing music. He was a photography buff and KTKT radio DJ ("the swing shift, 1 to 4 a.m. My ass was draggin'") who didn't want to leave Tucson. In 1957 he started at Sears, and retired from there nearly four decades later.

Paxton, incidentally, soon hooked up with Clyde "Skip" Battin and formed Tucson's The Pledges, which became Gary & Clyde, then Skip & Flip. Paxton split town in '59, was picking cherries in Washington when Skip & Flip's "It Was I" went to No. 11 nationally. Months later their "Cherry Pie" hit Top 20. Paxton, a true oddball, struck gold again in Los Angeles alongside fellow-eccentric Kim Fowley with The Hollywood Argyles ("Alley-Oop"). He would write or produce many hits, and Brian Wilson and Gene Clark became big fans early on. Years later he found God, scored a Grammy, and was tied to a scandal involving Tammy Faye Bakker. Battin would join The Byrds, Flying Burrito Brothers and New Riders of the Purple Sage.

(A 1950's Tucson music overview would also include Joe Montgomery, who in 1957 recorded several now-collectable singles for Liberty Bell in Phoenix. Tucson's first rock 'n' roll label, the short-lived Zoom Records, founded in 1959 by a pair of 17-year-olds, Ray Lindstrom and Burt Schneider, pressed now-collectable 45s by Tucson outfits Lonesome Road Rock, King Rock and The Knights, Jack Wallace and The Hi-Tones, and The Nightbeats with Linda Ronstadt's brother Pete on vocals.)

LaVerne's luminous voice excelled in pop, country, hillbilly, and bettered most making records in Los Angeles or New York or Nashville. But this was Tucson.

"I guess I didn't have the confidence to say I wanted to be a star," she says. "But it wasn't just some hobby."

She tells of hucksters and ex-DJs who'd try and woo her with management talk, but were only out for themselves. One landed her in a national contest in California. "Californians didn't like Arizonans," LaVerne says, matter-of-factly. "I didn't even perform and I only walked out on stage to be looked at. The winner was from back east, probably 8 years old, wrapped in furs."

Her popularity in Tucson is hard to comprehend now. Fans stopped her on the street for autographs, and letters poured in (some sent snapped photos of her performing on their TV set). Shows were standing-room only.

What is more incredible is David and LaVerne married nearly 40 years after meeting each other as students at Amphitheater High School. They met again in the late 1980s because David was on the reunion committee of Amphi's 30-year high-school graduation. She called him and they got to talking about a band he was in with Howard Smith, the very cameraman from Channel 13 back in '53. "He sent a list of songs over, big-band stuff. David played bass, Howard guitar, and we got three numbers worked up."

* * *

David and LaVerne live on a well-kept street on Tucson's northwest side. The two-story home's interior favors vintage Victorian, from wallpaper to delicate china collections, and suffuses a potent sense of someone else's nostalgia. An old windup Victrola in a living-room corner plays an assortment of 78s and framed pictures show children and grandchildren. One shows LaVerne's mother in Tucson, looking like Mable Normand in Victorian dress. A flatscreen off the dining room and kitchen dominates, and a double door opens to the backyard, into LaVerne's walk-through rose garden.

David, trim, gray flattop, glasses, wears a blue Star Wars T-shirt. He spends much time in a well-organized room upstairs, both a little recording studio and office. The ex-radio man and musician is a tube electronics whiz who loves World War II aircraft and models. Both LaVerne and David are long on moderation; only elaborate on what they remember, with no embellishment, offering documentation or photos in lieu of the hazy or forgotten. They are careful not to hurt feelings of anyone, living or dead. A kind of LaVerne foil, David injects self-effacing slapstick into their remembrances. His laugh an addendum. It is like the two of them inhabit the same call-and-response song.

LaVerne's chestnut hair is piled up and pulled back, eyebrows dark and sculpted, and her speaking voice bends to a slight Texas beat, likely of her father. She finishes sentences sometimes in classic Yankee patois, like, "Wouldn't ya know it." She is how I imagine a great country singer aging, my credulous imagination of a life of happy endings. Something about her carriage demands attention, even respect, not because she is 80, because it is who she is. A sort of X-factor—a vague yet potent charisma—that drew people to her 70 years ago, now filled with landmarks of a full life. She would never believe any talk of charisma and X-factors about herself because she is not aware. Norma Desmond does not live here.

Yes, by high school LaVerne maintained a sizzling music career pressurized on promise with no release valve, because there was nowhere to go, unless her family moved away. "It was a difficult life for me," she says, standing at her kitchen table, leafing through photos of her teenage singing days. "I was not one to brag. I was very quiet. But girls resented me, or were jealous or didn't like me. Boys were afraid of me."

"It's true! David cuts in from the couch. "I was one of those boys afraid to talk to her."

LaVerne shakes her head. "I was a freak. Only a couple older boys ever asked me out. Singing was always therapy for me."

Not the best student grade-wise—LaVerne would miss school for gigs but was the only one of her siblings to graduate high school.

"I didn't miss school on purpose," LaVerne says. "If anything, I lost a lot of sleep. I tried my best to keep up my grades. Unfortunately, education was not stressed in our house. There was very little on my parents' side."

LaVerne's English-born mom Alice grew up in France and joined The Ringling Brothers circus at 17 as a foot juggler, which brought her to America. She got into Vaudeville and also performed on the expansive B.F. Keith theater circuit. In Texas, Alice met Leonard "Bud" Davis, a tough cowboy rancher. He trained animals, spoke fluent Spanish, and led parties of wealthy folk into Mexico to hunt and trap. "They'd go on mules," LaVerne says. "He cooked all the meals on the fire."

Her mom, though innately elegant, was tough, and overly possessive of her children. She was never fond of in-law sons and daughters. She was a bulldogger too, could jump from a moving Model T car onto a running bull. "She would take the bull down," LaVerne says. "It was all leverage."

During the Depression, LaVerne's parents lived in a tent with her three oldest brothers. Dad trapped and sold the animal hides to survive.

LaVerne was born in Douglas, Arizona in 1939, the eighth of nine children, when Mom was 44. The family moved around, landed on a ranch in Patagonia before settling in Three Points outside Tucson, then all water tanks and dirt roads. The family owned cattle, and LaVerne rode a horse to school at 6 years old.

Hard-working papa Davis was not well educated but smart. "He had little finesse," LaVerne says. "He sometimes had difficulty telling the truth. He'd embarrass me with his BS-ing and bragging about me to others that wasn't true. It's funny," she adds, "he was a very likable guy."

Dad scored extra work on films shot at Old Tucson movie studios and LaVerne would accompany him to sets. She once got to know Lee Van Cleef, who warned her of few rewards in showbiz. She sang with actor Chief Thundercloud (the first Tonto on TV's The Lone Ranger) on the concession-stand roof at Tucson's Biltmore Motor-Vue.

Her parents worked steady at Consolidated Aircraft, modifying World War II bombers inside hangers at the Tucson airport. ("Mom was like Rosie the Riveter.") They opened The Walk-In Café on Sixth Avenue in Tucson, ran it for several years after WWII. "My mom made food from scratch. My older sister dropped out of Tucson High to work there."

Her brothers got into rodeo young, becoming professional bull fighters or clowns, "and one, Jim Davis, became a saddle maker."

Mom coached LaVerne on the ins and outs of performance, work that paid dividends in acting, which LaVerne pursued. In her junior year she scored a best actress award for The Little Dog Laughed, and did the Judy Garland part in Meet Me in St. Louis.

"Mama was savvy," LaVerne says. "I never argued with her on any performance ideas. It was total respect there."

* * *

Even before radio began spinning actual records in earnest, shifting away from its rotating menus of serials, comedies, news and variety shows, kids could listen to live performances of their favorites and dream. Radio shows boomed in from Shreveport, Louisiana, and Bakersfield, California, for example. The Grand Old Opry would lull LaVerne to sleep at night as a girl. She fell in love with pop too, Judy Garland and big-orchestra singer Doris Day. Later Patti Page, Joanie James and Connie Francis. LaVerne tuned in to Your Hit Parade on the family radio, and spun 78s on the Victrola record player someone had given to her parents. A stack of old 78s came housed in the player, including a few by Jimmie Rodgers, which hooked LaVerne. By third grade she taught herself to sing along to songs on the radio. "I learned Eddy Arnold and Marty Robbins songs on the jukebox in my parent's café."

In Tucson, radio boasted varied live radio broadcasts often featuring great, resourceful shows. Here is where LaVerne's Southern Arizona radio fame rose:

KOPO radio broadcast live from the Open Door Night Club on Benson Highway (torn out when I-10 went through), where LaVerne first sang with Dean Armstrong in 1949, at a Sunday matinee. Those days KOPO would send an engineer out to announce, and he'd sometimes return with broken equipment and tales of having to duck under tables after fights broke out. Rough in the classic beer-joint way, some called it a "skull orchard." There was the dicey Chanticleer bar too, out on Sixth Avenue.

LaVerne sang in those places often as a preteen. "It was exciting for me," she says. Her dad and brothers were protection, and Dean Armstrong loomed as a father figure.

LaVerne's dad began booking her live shows, sometimes on bills mixing country and pop music with acrobatics and Hawaiian music. Sometimes bandleaders would request her to come out and sing. Sometimes she'd change costumes between sets, from her customary cowgirl wear (with satin bellbottoms and glossy snapped shirts) to a billowy dress, to switch from country to pop. Her mother made all LaVerne's stage wear.

She sang and yodeled on KTKT radio, at the actual radio studio, backed by bass, guitar and violin. "I was 11 then, the station was just off Miracle Mile." On KVOA radio in '51, she starred on a weekly show called Trailer Time, which involved a live remote broadcast from Tucson trailer parks, a thriving community that had its own newsletter. Residents of said parks would write song requests to KVOA and LaVerne and band would play them. LaVerne remembers the "trailer parks in those days were very nice, with recreation rooms."

She toured with a KVOA radio revue called Sage Brush Frolics in '51 and '52, performing often at the old Kinsley Ranch in Arivaca Junction south of Tucson, its big ballroom.

KCNA radio featured LaVerne weekly, Saturday night dances broadcast live from the Tucson Sports Center on West Congress, from 1950 to '52. The station's Bob McKeehan had a radio show called Arizona Hayride, and his Arizona Hayriders featured LaVerne. The roadworthy western dance band filled rooms in Nogales, Duncan, Elgin, Ajo, Benson, Patagonia and Douglas. The power of KNCA radio, which boomed into Mexico and California, ensured the venues were full of entertainment-starved rancher families and kids.

LaVerne would win radio contests. One trip to KPHO radio's Lew King Show broadcast live from Fox Theatre in Phoenix. Sold-out, mostly kids. A recording of LaVerne on that show still exists. She was awarded the title of Little Miss Arizona.

More TV, sometimes live from Tucson Gardens ballroom on Lester Street, "which," she says, "was just beautiful in those days." Even KOOL-TV in Phoenix, where she once played with Gene Autry.

At 14 she met Wade Ray at the Open Door. "He was a performer that you just can't imagine," she says. "He'd been doing it since he was 4 years old."

LaVerne couldn't have known but in five years she'd star in a Vegas residency with Wade Ray, this Indiana fiddler who moved to Hollywood and hit big with records, and in TV and film. He had mastered a glossy blend of big band and country and honkytonk, was a huge Nevada casino draw and a Golden Nugget regular.

Around 1954, Kenny Smith, the steel player from Armstrong's combo, left to form Kenny Smith and the Westerners (who released a 45 called "It's Rodeo Time in Old Tucson," which became the official Tucson rodeo song). LaVerne was a regular with the Westerners and did myriad shows and weekly Saturday-night remotes from Tucson Gardens ballroom.

* * *

Timing was everything in the Old Pueblo, its patina of inferiority could take one only so far. LaVerne did not make a record and whatever proper recordings she made no longer exist, save for a few live performances. Just after her 1957 high-school graduation, in lieu of attending the UA, LaVerne moved to Los Angeles. She found L.A. beset with hustles and cons. She lasted four months.

She returned home discouraged but turned a favorite singalong into prophecy by becoming a cowboy's sweetheart and marrying a rodeo star. Changed her last name to Mason, got pregnant, and quit music. Just like that.

"He had borrowed a car to pick me up in Tucson and take me to Nebraska," LaVerne says of her first husband, choosing words selectively. She stays faithful to never utter a bad word of anyone, especially the father of her first born. My sense is the guy was cruel.

"I took my guitar with me but at this point there was no career," she says. "So I was pregnant and married. And my mother and father were not too happy. It was not a happy getaway."

Nebraska didn't last long and she moved back to Tucson.

"He would take off and do a rodeo and make money, and it would get spent. I got a job at a drug store and was laid off because I got hired for Christmas rush. It wasn't a good time. I had to move in with my mom."

While counting pennies with a newborn, a husband in and out at rodeos, the phone rang. One of those perfectly timed calls doubling as a life-changing moment. It was Kenny Smith with Wade Ray on the line, the same Wade Ray her parents brought her to see five years prior. Kenny was now with Wade in Las Vegas. They said, "We have a spot for you."

The teenager who defied common gender roles, who got her radio start at 10 years old on Tucson's KCNA had made it to the storied lights of Vegas alongside an American superstar.

"Wade took me outside of the Golden Nugget and showed me the marquee," LaVerne says, "and my name was up there, at the Golden Nugget."

* * *

The slack-wristed Americana of Sammy, Dean and Joey, and Frank's high-art thugisms, were just mainstreaming in 1959, and Vegas was not yet the overly romanticized cesspool of macho greedy desires. Life-shifting for a soon-to-be single mother, she was resigned to the fact all manner of men hit on her. "Oh, most all did that," she says. Then adds, "My baby was always with me. And when I was with Wade I was so happy. Wade was a good man. My only stress was my husband. I couldn't trust him anymore, couldn't believe him anymore."

All sorts attended Wade Ray shows, and LaVerne rubbed elbows with sundry types, from Texas gangster Benny Binion to rising country man Roy Clark, from Wayne Newton to Jim Reeves to Bob Wills. She befriended singer Sue Thompson, whose songs LaVerne sang at 12. ("She was like a mother, 12 or 13 years older than me.") She shared a dressing room with rockabilly queen Wanda Jackson, and the two became friends. "And Wanda wanted to sing what I was singing!" LaVerne laughs. "Wouldn't ya know it."

They'd do 32 weeks a year at the Golden Nugget, with runs to Reno and Lake Tahoe. The young mother didn't imbibe time-honored show-biz restoratives, booze and drugs—even suggesting such amuses her. But others did. "Sometimes we'd play 11 till 6 in the morning at the Nugget, and leave to go to Lake Tahoe, and they'd pop pills."

She had her own 25-foot travel trailer, with a living room and a bathroom. In those days, $125 was a substantial weekly wage for her, even if it was "not as much as the guys, I'm sure."

A highlight was LaVerne's mother finally coming to see her perform at the Golden Nugget. "She cried. I can still see her in my mind. The lights lit up the back of her. It was dark but she stood out, and I knew it was her. It had been almost a year since I saw her last."

The Vegas life overwhelmed the young mother and she quit after two years. "I don't want to expose my daughter to that ... I didn't want to drag her all over. I didn't want to worry about someone else taking care of her. And I needed to get a divorce."

LaVerne went and stayed with her mom, now living in Phoenix after separating from her husband. "They were like that, on and off," LaVerne laughs. "Ooh, boy, they had interesting lives."

She found singing gigs in Phoenix, not easy for a woman in the early 1960s. At a dinner club called the Steak House on north Central, at the neon-lit Guys and Dolls club near the airport singing three sets a night. Arizona Republic entertainment columnist (and club owner and famed Mascot Records founder) Jack Curtis wrote of her several times: LaVerne had a "beautiful voice" and was "the prettiest attraction currently appearing at any club in the Valley."

She fell in love with a man who worked in sheet metals and remarried. "I met my kids' father and that changed everything," she says. "I needed security, for my child. He was a good man, but it turns out not the love of my life. But it was good. In 1963 I had my first boy, and I spent 30 years in Phoenix raising kids."

Her voice softens revisiting moments from decades earlier, weighing trade-offs and private responsibilities of raising her four children versus a career in song.

LaVerne offers a little chuckle. "I sang in a choir in church."

Once a year she would sing at a bowling-league gathering. In the mid-'70s she organized a band for a Little League baseball dance and dinner—two nights total.

That marriage ended in divorce. But not before she renewed a friendship with former classmate David Lawrence at that 30-year class reunion. She started coming back home to Tucson in 1989. David and LaVerne married in 1993.

LaVerne sang at that reunion. She hadn't performed in years, and many remembered her. "I was very nervous, I went into the bathroom and I had pains in my stomach."

* * *

Backward gazes from any 80-year-old woman's vantage could never be all lovely Arizona sunsets, but LaVerne is hugely accomplished away from music. As a musician, LaVerne Davis Lawrence never considered herself anything other than a girl from Tucson with a guitar. A different self-fulfillment had taken its place, and ways of contributing to some greater good. It would have been easier to self-destruct. She is very "close and proud" of her four children and grandchildren. Her own children sing too. In 2003 they banded at Tucson's Women's Club and performed "Man of Constant Sorrow" after the film O Brother, Where Art Thou, while her youngest daughter sang a different song on the bill.

LaVerne ran a private day nursery for years and current photos of adults she cared for as children are displayed in the couple's house.

She is with a man she adores and has known for more than 65 years. That man steps to the stereo and plays a Golden Nugget performance of LaVerne recorded in 1960. He is still in awe. No wonder. Her voice is pure-toned, as if Brenda Lee and Patsy Cline were one. The feel of it utterly incommunicable to another human being.

With David, and back in Tucson, LaVerne began singing again. She would occasionally sit-in with old friend and bandleader Dean Armstrong at his weekly residency (which lasted more than four decades) at Li'l Abner's Steakhouse, and a few other gigs. She and David put together a combo with crack musicians, featuring a violin, keyboard, sax, rhythm guitar (LaVerne would play on some songs), bass. My own father Howard Smith on lead guitar. Called themselves LaVerne and David and their Western Swing Band, and LaVerne apologizes. She is forever uncomfortable seeing her name appropriated in any kind of band moniker. Too embarrassed, she says, or it could be that Tucson unworthiness thing. The band did one show a year, venues like the Tucson Women's Club and the FOP Lodge. Sometimes LaVerne's brother Gene would come out and sing. Berger Performing Arts Center hosted the last gig in 2012.

In 2008, LaVerne's former partner Kenny Smith was in failing health and living back in Arizona. She would collect her guitar and go see him out at his place near Picture Rocks, get him to play songs.

LaVerne sings Sunday mornings now at the Sanctuary United Methodist Church in Marana, Ariz.

* * *

LaVerne pulls out her blonde Gibson acoustic guitar and takes a seat at the dining-room table. Chords strummed gently, the croon and hushed vibrato intact. That X-factor too, still. She sings Eddy Arnold melancholy in waltz time: I'm sending you a big bouquet of roses ... One for every time you broke my heart.

Then suddenly she is done singing and talking for the day. She and David tire fairly quickly and LaVerne lately endures pain in her feet and lower legs. But before evening falls, the couple step into the living room to their old Victrola record player. LaVerne bends down and pulls from its cabinet a stack of 78 records. She flips through and stops at Clyde McCoy's "Sugar Blues" and plops it on the player. She winds the contraption up and David drops the needle on the spinning disc and crackly wah-wah trumpets and bouncing guitar fill the living room. LaVerne dances a bit in front of the player. Music as life. As a focus of both escape and longing of the attachments to loved ones who are now gone, including all but one of her siblings. Most everyone she has ever played with, and adored, are gone too, those who either helped her or backed her along the way, including Dean Armstrong, Kenny Smith, and my father, the guy who first broadcast her to Tucson living rooms.