In Arizona, Indian gaming is an $830 million-a-year income for tribes. But as gaming tribes returned to negotiating new 10-year compacts with the state this week (continuing a year-long process), the climate suggests the courts, the Legislature and the governor's office, not to mention Washington, D.C., might try to change key elements of laws governing these compacts.

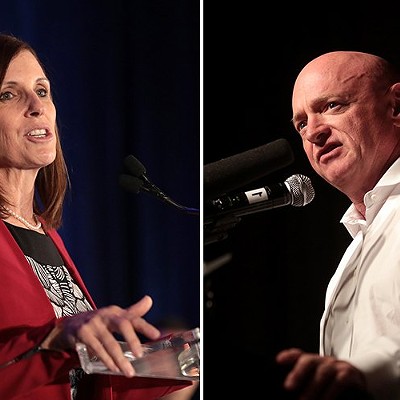

"I don't think that Gov. [Jane] Hull is a big fan of gaming in general and she's consistently said that," says David LaSarte, executive director of the Arizona Indian Gaming Association, which represents Arizona's 17 gaming tribes in the negotiations.

But LaSarte says Hull seems to recognize that Indian gaming addresses important unmet financial needs of the tribes. "Because of that, she is willing to move forward and take care of these compacts," he says.

Former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt was a supporter of Indian gaming and the right of sovereign Indian nations to pursue gaming to offset Washington's under-funding of Indian programs. Norton's ascension suggests a possible sea-change.

Norton's first two public speaking engagements concerned Indian affairs. She expressed support for tribal sovereignty and reiterated President George W. Bush's pledge to repair BIA's 185 Indian schools and replace six of them (two of which are in Arizona).

But Norton also supported giving states more power (something Bush is pushing as he picks up the states' rights torch of former President Ronald Reagan.) And her record on Indian issues as Colorado attorney general was mixed.

In a 1996 speech when Norton was the Colorado attorney general, she loudly supported property rights and the 10th Amendment, which gives all powers to the states that the Constitution does not expressly assign to the federal government.

Norton also worked under former Reagan Interior Secretary James Watt at the conservative Mountain States Legal Foundation in Denver, which led the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1980s. Environmentalists have referred to her as "James Watt in a skirt." Watt once described Indian reservations as "socialism at work," and Indians fear Norton's attitudes toward Indian gaming and reservations might reflect this attitude.

According to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Norton fought the interests of all minorities in Colorado.

"Every federal dollar and every federal program aimed at Native Americans comes through Interior, so anything that affects the direction of that department is a big concern," says LaSarte.

Arizona's tribes fear if they get into disputes over the current negotiations with the state, Norton will side with the state rather than the tribes.

When the Tohono O'odham Nation first went to then-Gov. Fife Symington asking him to sign the state's first gaming compact, he refused. Babbitt then told Symington to sign the compact or the federal government would do it for him.

Most of Arizona's 10-year gaming compacts with tribes are set to expire in 2003, a year after Hull leaves office, but Hull recently suspended renewal negotiations when the state's horse- and dog-racetrack owners filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court seeking a ruling to declare Indian gaming illegal.

A ruling on the racetrack owners' lawsuit is not expected for months, but Hull decided to continue negotiations with the tribes even though her office says she will not sign an agreement or any compacts until the lawsuit is resolved.

"Their [the racetracks'] litigation alleges the current compacts are illegal," says LaSarte. "If that type of reasoning were applied nationwide, it would mean that most of the Indian-state gaming compacts in the nation would be illegal."

At issue for the Arizona tribes is Hull's demand they pay 7 percent of their net casino profits for a "community benefits fund." The governor believes tribal gaming draws away lottery revenues. Other gaming critics claim the state's Indian gaming industry doesn't put one penny into state coffers.

"The tribes give a tremendous amount of money to charities already and put a lot of money into cooperative projects with local governments," answers LaSarte.

The state's own Department of Gaming said in its 2000 report, "Indian gaming contributes to many charitable organizations throughout the state" and "provides major economic benefits to tribes, rural communities and Arizona businesses."

The Ft. McDowell Tribe, for example, gives $1 million a year to state universities, and the Tohono O'odham Nation says it puts an estimated $12 million a year into the local economy in paying gaming-related wage and sales taxes.

"Basically the positive impacts that gaming tribes are trying to make on the non-Indian community weren't taken into account with the 7-percent impact fee," says LaSarte.

The other bone of contention is summed up in an August 2000 letter from Hull's office to the tribes that states, "Before the governor will agree to new compacts, there must be an enhanced regulatory structure with a significant, not reduced, role for the state." The state wants "casino police" from the state Department of Public Safety to patrol tribal casinos. Tribes say that's a violation of their sovereignty.

Again, the state's gaming department report said, "Indian gaming is well regulated with tribal, state and national oversight and regulation. Some believe it is in danger of being over-regulated."

Gaming tribes' expanding operations give them some long-needed political clout. During the last five years, tribes with casinos spent almost $40 million on political contributions to federal election campaigns, seeking to minimize federal oversight of casinos and keep the operating budget of the National Indian Gaming Commission at its current $8 million. But still-powerful gaming foes seek $25 to $40 million for the commission so it can toughen Indian gaming regulations.

Norton is under pressure from both Indian nations and the courts to deal with a lawsuit over how the BIA has handled a nationwide Indian Trust Fund. The federal government set up the trust fund more than a century ago. Fee revenues from activities on Indian land such as oil drilling, livestock grazing and logging go into the BIA-administered fund for investment and distribution. But many payments to tribes have been skipped, and many records of the fund's activities are missing, or are conflicting and confusing.

Up to $10 billion might be owed to tribes from the $500 million-a-year system involving 300,000 Indian trust accounts.

A landmark 1999 ruling that a federal appeals court upheld in March ordered Interior to provide the court with quarterly progress reports on the agency's efforts to untangle the trust fund mess. The latest progress report shows the work to clean up the trust fund not only is moving too slowly, but BIA doesn't have enough money to complete the project. Bush, however, proposes a 4-percent cut in Interior's budget for next year.

And Bush's nominee to head the BIA is Oklahoma Secretary of Transportation Neal McCaleh. Reagan named McCaleh to the Commission on Reservation Economics, a body whose 1983 report suggested Indian tribes be deprived of some of their sovereignty rights. No action was taken on the report's findings.

Having Norton as head of Interior, and overseeing the BIA, is not likely to help Arizona tribes if gaming compacts stay bogged down. "Trying to craft a one-size-fits-all compact that addresses the different needs and concerns of 17 tribes and the governor has been challenging," says LaSarte. "We're progressing, but slowly."