Breast cancer can happen to anyone. It doesn't just happen to women who have strong support networks in the form of family and friends. It doesn't just happen to women who like the color pink. It doesn't just happen to women who manage to feel confident and beautiful when they're bald and suffering through cancer treatment and the sometimes astounding number of associated surgeries.

It happens to women like Urania Ramsay, who found a lump in her breast in 2014 while she was still breastfeeding. It happens to women like Nell Haynes, who was getting up at 5 a.m. every day to go running when she was diagnosed in 2012—and continued to wake up early for her jogs through her treatment. It happens to women like Taryn Tewksbury, who went from being excited about finally having the health insurance to cover a routine mammogram to being shocked when she got her test results back in April 2015.

"I didn't really know what the next step was—I knew I should do something, but I just didn't," Tewksbury said.

Then she met up with an old friend at a Susan G. Komen walk, and explained she wasn't doing too well. Her friend's response? "Let me introduce you to Anita."

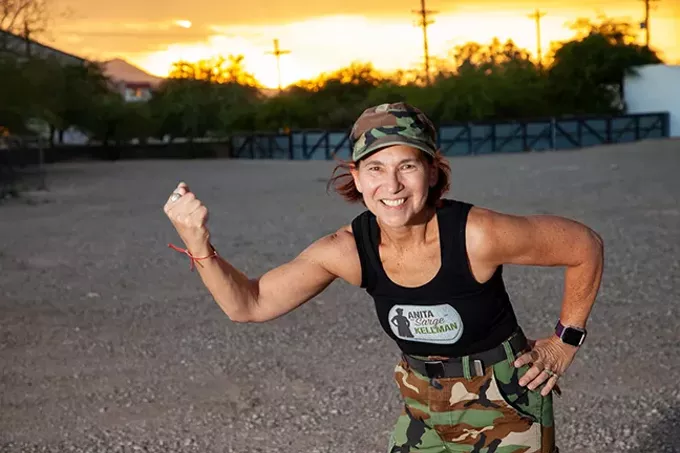

The Anita in question is Anita Kellman, also known as "Sarge"—the founder of the Kellman Beat Cancer Boot Camp, a fitness program for cancer survivors and those who love them.

Though it's now nationally recognized, the program didn't start with such big dreams. Kellman, a clinical liaison for patients undergoing biopsies and other procedures in Tucson, was running a boot camp class for the City of Tucson when one of the attendees was diagnosed with cancer. Kellman encouraged her to keep coming, and a year later, her treatments done and officially declared cancer free, she mentioned attending bootcamp had gotten her through some of the worst times she'd experienced. Kellman realized there was a need for something bigger.

And so she started this specific program, a way for those touched by cancer to get together and get some endorphins flowing, plain and simple. When people tell Kellman they're not sure about joining her program because they're not "group people," she smiles and tells them they'll fit right in. She counts people like Haynes, who came in hesitantly and now attends classes every week with her husband (and sometimes even her children), as a success story.

"I think the hardest part is going the first few times, because it's a club you don't want to be a part of," Haynes said. "Nobody would choose this journey, but since you have to go on this journey, it's good to go on it with people who have been there or are going there."

Rethink Pink

According to the American Institute for Cancer Research, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide, contributing to 25.4 percent of the total number of new cancer cases diagnosed in women in 2018. It also tied with lung cancer for the most common cancer worldwide among both sexes (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer), contributing to 12.3 percent of the total number of new cancer cases diagnosed worldwide in the same year.

So, while the Kellman Beat Cancer Boot Camp isn't solely for breast cancer patients and survivors, or even for cancer patients and survivors, statistically speaking, most of the people who attend the camp are dealing or have dealt with breast cancer. But they are more than just cancer survivors.

"You don't want to be identified as cancer," Haynes said. "I don't like pink. I didn't like it before, and I don't like it now."

Gayle Sulik, a research associate at the University of Albany and the founder of Breast Cancer Consortium, describes the environment many breast cancer patients and survivors face, one in which they're expected to put on a happy face and start wearing a lot of pink, as a part of "pink ribbon culture," an overly commercialized and simplified, though often-well intentioned, view of the disease. She writes in her book Pink Ribbon Blues: How Breast Cancer Culture Undermines Women's Health: "Grounded in advocacy, deeply held beliefs about gender and femininity, mass-mediated consumption, and the cancer industry, pink ribbon culture has transformed breast cancer from an important social problem that requires complicated social and medical solutions, to a popular item for public consumption."

Kellman has long been a proponent of the idea that exercise can help to prevent cancer, and says openly that she, for one, would much rather prevent cancer than catch it early. Kellman wants to give her boot camp attendees the chance to take control of their lives through crunches and squats. Not, she says, through buying a pink blender that will bring money to some corporate giant.

Physical Strength for Mental Toughness

The National Cancer Institute indicates that higher levels of physical activity are linked to lower risks of several cancers. For example, a 2013 meta-analysis of 31 perspectives studies found that the risk for breast cancer was reduced by an average of 12 percent for physically active women. Studies also found that physical activity after diagnosis was linked to better breast cancer outcomes. For example, a large cohort study found that women who exercised moderately after a breast cancer diagnosis had an approximately 40 to 50 percent lower risk of breast cancer recurrence, death from breast cancer and death from any cause compared to more sedentary women.

The physical benefits of attending Kellman's biweekly boot camp are tangible in other ways as well. The Kellman Beat Cancer Boot Camp has been featured on shows like The Biggest Loser, and Kellman travels the country to lead events and help others start franchises of the group. She said the delight in people's faces after hitting a milestone like being able to do 100 pushups in a row never gets old.

"The whole idea is you don't need much to exercise," she said. "I like to do it outdoors because—aside from the germ issue with the gym—I like to people to be in the elements Let's lunge toward the mountains. Crunch and we'll look up at the blue sky."

Ramsay, the woman who found a lump while she was breastfeeding, expected to grow sickly and frail during her chemotherapy treatments, but found she actually gained weight due to a fluctuating appetite and low energy. She was desperate to feel confident, and to feel like herself again, and considered returning to drastic measures she had tried before, like taking a daily laxative. This time, she tried the Kellman Beat Cancer Boot Camp instead.

"I lost 25 pounds in the first year," she said. "I'm happy again."

A Different Kind of Support

Ramsay's happiness doesn't just stem from her new body. She started attending the Kellman Beat Cancer for the exercise, but ended up finding something she'd been looking for in the support groups she'd been trying out. With people taking turns sharing their stories and crying, she left feeling more depressed than heartened.

"[At the Kellman Beat Cancer Boot Camp] nobody's crying or boo-hooing," she said, then laughing a little as she added: "Other than when they're doing too many pushups."

While it's called a boot camp, Kellman understands the people who come to her classes are often in the middle of cancer treatment, recovering from surgery, or simply in the midst of an overwhelmingly emotional time. She asks only that those people give it the best they've got, even if it means modifying exercises or sitting some out. Sometimes, she realizes, it just means showing up.

"I can always think of a million reasons not to go, but I don't want to get that call from Anita asking, 'Why didn't you come?'" said Tewksbury, the woman who got news of her cancer after the mammogram she'd been so excited to get, "I'm just grateful for Anita. She's brought a really unique program to us and to Tucson, and I think she's changing the face of cancer survivorship."

A Crucial Community

It's hard to say where more of the healing is taking place: during the workout, where participants are strengthening their bodies, or before and after the workout, where participants are strengthening their friendships and their resolve. Having a community of upbeat fellow survivors (it's hard not to be upbeat with so many endorphins flowing) who can tell you what to expect—good, bad and ugly—can be invaluable. It also provides a blessed middle ground between the urge to break down and cry and the pressure to stay strong for loved ones.

"They don't have to put on the happy face like they do in front of the family, and it gives them strength to deal with the family," Kellman said.

Tewksbury said when new people join the group, everyone bands together to see if there's anything the person needs, whether it's transportation to doctor's appointments or someone to take care of them after surgery.

"It's the kind of friends that you make that, when your car breaks down at 2 in the morning, you call them and they'll just show up," she said. "It's kind of like being survivors of a shipwreck. We've bonded over life and death."

Kellman said one of the best parts of the program, to her, is watching people who didn't know one another before boot camp become such close-knit friends that they seem like they've known one another forever. But watching people find their physical strength and beat cancer is pretty incredible too.

"You put all of that together," she said, "And it's magical."

Beat Cancer Boot Camp sessions take place every Tuesday at 5:30 p.m. and every Saturday at 7 a.m. at Morris K. Udall Park, 7200 E. Tanque Verde Road. A $5 donation is suggested.