It's another hungry morning at the Casa Maria Free Kitchen on East 26th Street, where Brian Flagg watches groups of men lumbering along the sidewalk. Some clutch brown bags; others have already torn the bags open, gnawing quietly on bologna and cheese sandwiches.

This Catholic-affiliated kitchen, managed for years by Flagg, is hardly an opulent affair. But it is a critical one. Situated in a nondescript block building on a dusty corner, the charity feeds up to 500 folks a day, along with providing clothes, sleeping bags and blankets. It sometimes helps people pay their rent and utilities.

All of that happens on a meager budget of about $250,000 a year. So at Casa Maria, every dollar counts. That's why more than a few eyebrows were raised recently when the nonprofit turned down a $2,000 donation from Walmart. Speaking to a local newspaper, Flagg called the gift "blood money."

But as it happens, that move came with a silver lining: According to Flagg, his stance against the giant retailer sparked a flood of fresh donations from like-minded people across the community. "We way more than recovered the $2,000 that we lost," he says.

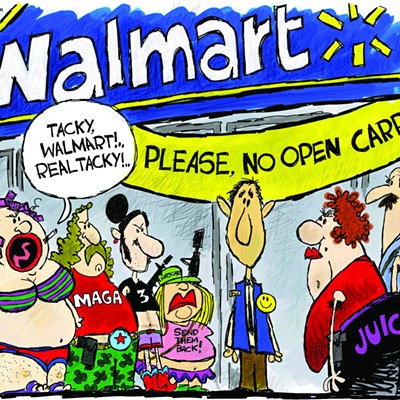

He considers that an ethical victory. "We understand that (Walmart) has really low prices. But we also felt that they pay lousy wages; they're anti-union; and they're detrimental to the survival of small businesses in areas where they open supercenters. That's why we felt we couldn't take the $2,000."

As it happens, Walmart's intended Casa Maria donation was among $15,000 distributed to local charities in celebration of a new Tucson supercenter near Kino Boulevard and 36th Street.

Nor was the retailer easily dissuaded. Following Casa's decision, Flagg says, "some guy from Walmart showed up and tried to give me $1,000."

Flagg says he thought hefty paperwork was required to get any Walmart donation—a notion the visitor scoffed at. "He said, 'Nah, forget the paperwork; here's a thousand bucks,'" Flagg recalls.

Again, the money was refused. "I told him about the issues, and about how they pay lousy wages," Flagg says. "And he said, 'Lousy wages? What do you mean, man? Look out there, that's my car.'"

Flagg pauses. "I think it was a BMW," he says.

After we left a message on the Walmart media line seeking information about Flagg's mysterious visitor, we received a call from the public-relations firm R&R Partners. It appears that R&R then simply channeled our request back to Walmart, and that's the last we heard from anyone.

Nonetheless, rejecting money in tough times—even from Walmart—was not an easy decision, Flagg says. "We got a lot of calls from people who were really angry and even hateful about it, too. So you know, it goes both ways."

Indeed, an Arizona Daily Star story about Flagg's decision was followed by vehement letters to the editor. "Flagg has no principles," read one. "I hope the hungry of Tucson and Catholics are paying attention. So, for my part, I can forget about any future donation to a Catholic charity."

But some were supportive. "Walmart's supposed low prices come at a high cost," wrote one reader, "not only to its workers who have no health benefits, to our community where local stores and manufacturers are forced out of business, but also to the factory workers overseas who supply Wal-Mart [sic] with cheap goods by working in crowded, unhealthy and dangerous sweat-shop conditions. ...Thanks, Brian, for refusing to let a giant corporation use Casa Maria to make them look good."

In the end, say experts, the polarity of these views highlights the risk nonprofits face by taking money from controversial sources.

"Best practice is if they have a gift acceptance policy to fall back on," says Michael Nilsen, spokesman for the Association of Fundraising Professionals in Arlington, Va. Beyond that, he says, there is no universally accepted standard. "It's really based on the culture of the organization. ...This isn't necessarily a black and white issue."

Nor is accepting such money while claiming neutrality toward the donor. Consider the numerous organizations that accepted small donations or volunteer hours from Rosemont Copper, the subsidiary of a Canadian investment company hoping to dig an open pit mine in the Santa Rita Mountains south of Tucson.

Those recipients eventually found themselves listed under "partnerships" on the company's website, alluding that they support the contentious project. Yet many of those so-called "partners" contacted by the Weekly hardly considered themselves to be partners of Rosemont. Instead, groups such as Tucson Values Teachers and Casa de Los Niños say they held no opinion on the mine.

"We have a Rosemont executive on our board," says Jacquelyn Jackson, executive director of Tucson Values Teachers, which lobbies for education support. "I wouldn't call them a major funder, but they certainly contributed."

Still, "we haven't taken a position on the actual (mine) issue," Jackson says. "We're kind of open to all comers in the business community."

Other recipients of Rosemont donations, such as the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona, see taking the money as sheer necessity. "When we accept donations from an organization, it doesn't mean we support that organization's business practices," says Food Bank spokesman Jack Parris. "We don't get into making judgments like that. ...We need to feed hungry people in Southern Arizona."

Several attempts to get a full explanation from Rosemont about of how such donations translated into "partnerships" have been unsuccessful.

Nonetheless, nonprofits do bear responsibility for how their names are used, Nilsen says, whether that includes being listed as a Rosemont "partner," or trumpeted in newspaper stories about Walmart's generosity. "Frankly, if I was the charity, I would be a little careful. 'Donor recipients' might be one term. But to me, 'partners' connotes a very different sort of relationship."

A nonprofit's currency "isn't necessarily money," he adds. "Its currency is its reputation. That's really what it has on the line. I think charities always need to look at how their names are being used if they are given a gift. Their due diligence doesn't just stop with accepting the money."

Back at Casa Maria, Flagg tightens his sweatshirt against the December chill and glances at the dissipating lunch crowd. The way he sees it, even cash-strapped nonprofits can't just take money from hot-button organizations—whether it's Rosemont or Walmart—while claiming to be impartial.

But he certainly knows the temptation. "Money is really, really tight," he says, "and people are really, really poor. They have extreme needs, and so do the agencies trying to support them."

That distress is eagerly exploited by the Rosemonts and Walmarts of the world, he says. "It's part of doing business in America. You try to make yourself look good by giving out small amounts of money."