I'm sorry to be putting you guys through this... I hope you guys know I love you and I will miss you but I'll be back. And I will make you guys proud of me. I don't know how but I will. I love you mom and dad. Love Branden.

—Branden Roth, in a 2015 letter from state prison to his parents

When the guard at Pima County Jail found Branden Roth, he was lying on the floor of his cell, covered in blood.

His cellmate, King Yates, was lying on the bottom bunk with blood on his pants. He ignored the guard's first two orders to step out before calmly getting up and walking out of the cell.

Headphones lay on the bed. Under the bed was a red sock full of batteries.

Roth, 24, who was awaiting sentencing for felony theft charges, was pronounced dead at 10:12 a.m. on April 19, 2017.

He was found in a pool of blood, his face covered in lacerations and bruises. He had what looked like defensive wounds on his hands and marks on his neck where a cord had been tightly bound. The autopsy would later show that bones in his neck were fractured. He had broken teeth. His jaw was dislocated. Official cause of death was strangulation.

Yates, 23, is now facing charges of first degree murder for Roth's death, likely to go to trial in Pima County Superior Court later this year. After pursuing the death penalty, Pima County prosecutors changed course after evidence surfaced that Yates—who was already facing charges of shooting his wife in the head—had not been receiving the dosage of antipsychotic medication that he was previously court ordered to take.

Only thing I want to do when I get out is start over... Well I'm going to stop talking about this stuff, about being in jail, 'cause it's making me cry. I realize I can't hug you guys... And it sucks coming to this realization, but I put myself in this situation. Mom, you were right.

—Roth's 2015 letters to his parents

The police were waiting for Carrie Walker when she got to work. They asked for a private place to talk. Carrie, a 49-year-old elementary school custodian, led the officers to an empty room. They told her that her son had "passed away" in jail and warned her to not watch the news.

She went out to her truck and found the articles on her phone. She drove home, and that's all she remembers from that day.

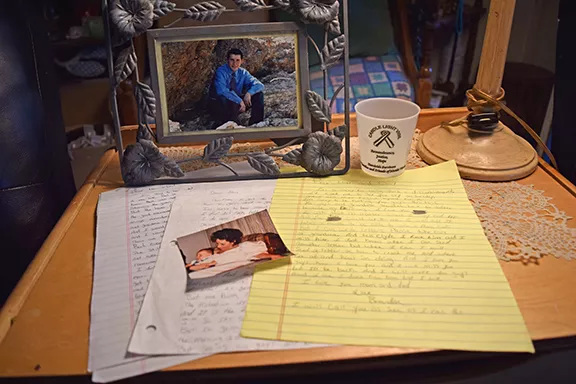

Almost nine months after Roth's death, Carrie's still numb. She spends a lot of time at home, with her husband, Rodney Walker. Photos of them smiling line shelves next to recently emptied ashtrays, carefully tended plants and photos of her handsome, young son.

"They say I'm still in shock, and I've got PTSD and all this other crap," Carrie says. "But I've got to fight for Branden now. I want people to know Branden wasn't the inmate, the criminal. He was a great person."

Carrie turns the pages of the baby book she carefully filled with notes and photos, over 20 years ago. He's gone, but it doesn't seem real, she says.

She raised Roth and his sister primarily on her own. But Carrie's father Joe Jensen was Roth's best friend growing up. He picked Roth up from school every Friday. He took him to construction sites, where he worked as a plumber. And Roth wanted to be just like him, calling to say goodnight every evening.

One Friday when Roth was 13, Carrie picked him up instead of his grandfather. At 49, Jensen had had a massive heart attack at work and died.

"Branden just fell apart," Carrie says. "He was really never the same after that. He wanted to be with my dad."

For a time, she worried Roth was suicidal. But when Carrie met Rodney a year later, Roth's adoration for his grandfather transferred. Everywhere Rodney went, Roth was at his side. Rodney remembers the first time they met.

"He just ran out the door and introduced himself, and ever since then, we were close," Rodney says. "Ever since then, that was it—we did everything together."

They watched movies and played video games. They went to church some Sundays. And Rodney taught Roth to fix cars. So Roth started fixing all his friends' cars but usually had to call Rodney to come save him, elbow deep in grease and oil.

More than anything, Roth loved his dogs Bonnie and Clyde. And when they died, he held on to their ashes, waiting for the right time and place to scatter them.

Roth was a kid who made his mom pull over when they saw roadkill, so he could bury it. As an adult, he cleaned house to Abba's "Dancing Queen." He went antiquing and bought little gifts for his mom. But what his mom misses most is the way he smiled with his eyes.

I love you both so much. You mean the world to me. And yes, I learned my lesson. No more dumb stuff...

—Roth's 2015 letters to his parents

Roth's first serious brush with the law came when he was 19 years old, in July 2012. He and a few other guys robbed a house. They stole jewelry, electronics and three cars.

Rodney and Carrie say Roth got involved at the behest of his then-girlfriend. When he was arrested, at an apartment building the same day of the crime, he was with a girl who knew the homeowners and knew they were out of town.

He spent two days in jail, then didn't show up for court four months later. A warrant was issued for his arrest. On Dec. 13, he called his mom from Pantano Baptist Church. He was turning himself in but wanted to tell her goodbye. When the police came, he asked them not to handcuff him in front of his mom. They agreed.

As Carrie watched them take Roth away, she experienced that surreal feeling that's become her new normal—it just didn't feel real.

Roth pleaded guilty to felony burglary charges and spent two months in jail. During this time, he got closer to his parents. They visited him every weekend and wrote letters to the judge on his behalf.

He was sentenced to five years of probation, but he just couldn't keep it together. He violated his probation multiple times, failing to take required drug tests, pay fines and meet with his probation officer. After doing additional jail time for these violations, in August 2014, his probation was revoked and he was sentenced to time in state prison, where he would spend a year and three months.

Once he got sent to the Florence State Prison, he didn't want his parents to visit him.

"Especially, he didn't want Rodney to see him like that 'cause he knows he disappointed Rodney," Carrie says. "That was the worst thing to him because Rodney was so much like my dad."

But Roth wrote them dozens of letters.

Dear mom and dad, I'm going to start this off by saying I'm so sorry... It was my mistake, and I have to live with the consequences. You guys mean the world to me. When you came and visited me, it made me so happy. I appreciate everything you guys do for me. You helped me so much. I hate that you guys have to see me in here, and I'm sorry for it...

—Roth's 2015 letters to his parents

Carrie used to worry about Roth. But after he got out of Florence in November 2015, she believed he was going to be all right.

Roth started dating Sydney Osment soon after. A few years older than him, she came to the relationship with her own host of problems. Five months in, she got pregnant, and within a month, their relationship fell apart.

Roth and Osment didn't see each other much after that. But he never stopped talking to his mom about his soon-to-be-born son and how much he wanted to be in his life.

Carrie and Rodney sold Roth a '95 Kia Sephia on a payment plan. Rodney put in a good word for Roth at BrakeMax, where he worked, and they hired Roth as a mechanic, around October 2016.

A month later, Rodney's boss told him Roth stole an expensive diagnostic tool, a relatively small tool that could easily fit in a backpack. It was worth thousands of dollars, according to court documents, but Rodney estimates it closer to $300.

Roth pawned it that same day. USA Pawn gave him $200. He showed them his ID and scanned his thumb print.

Carrie and Rodney have no idea why Roth did it. They were both mad. Carrie said she and her son needed a cooling off period. They weren't speaking much, but on March 26, 2017, he texted her: Just wanted to let you know that you're a grandmother.

Osment and Roth hadn't spoken. No one understood why Roth sent Carrie that text. Osment went into labor two days later and gave birth to their son.

It was April 7 when Roth pleaded guilty to trafficking in stolen property and entered Pima County jail to await sentencing. He was placed in a cell with King Yates. Twelve days later, he was dead. He never met his newborn son.

Yates was brought up by his great aunt, at the end of a partial cul de sac on Tucson's southeast side. His mom went to prison outside Fresno, California, when he was 2, and his father was in Inglewood, California, according to court records.

At 15, he was charged with a misdemeanor assault. By his 18th birthday, he had additional run-ins with the law for drugs and possession of a firearm.

When he was 18, in 2012, an ex-girlfriend, and mother of his child, successfully filed a restraining order against him.

Two years later, he attacked another ex-girlfriend. She told police he hit her several times in the face and cut her with a butter knife. He was charged with a misdemeanor assault.

Yates married Cassandra Shaylor in September 2014. In the three months that followed, police responded at least three times because of his violence towards her. He yelled at her, slapped her, pulled her hair, pushed her and threatened to shoot her in front of his sister, her grandparents and strangers, who all felt compelled to call for help.

In November he was arrested at a Motel 6, after staff called the police because they heard fighting. Police found bindles of cocaine, heroin and meth, as well as a 9mm handgun. He was arrested and the state recommended a $10,000 bond, noting he had a history of violence, drug use and prior felony convictions.

Two days later, he was released on a $5,500 bond. Cassandra had secured his bond with titles from both their vehicles.

In March 2015, his charges still pending, Yates showed up at a hospital, Cassandra by his side, saying he'd been poisoned. He wouldn't let his wife out of his sight, even to use the bathroom. She had bruises on both her arms and legs and was noticeably scared.

When the attending nurse got a chance, she asked Cassandra if she was all right. Cassandra said Yates accused her of poisoning him and had hit her in the head and stomach. He had restrained her and said, "I could kill you."

Police later charged him with misdemeanor assault and domestic violence.

Because of Yates' behavior, the courts asked for an examination of his mental condition, in regards to his pending charges related to drug and firearms. Court records say Yates was in denial of mental health issues, that he had been exhibiting paranoia, that his state had deteriorated drastically since his arrest at the hotel.

He believed the government was spying on him, trying to poison him. He said neighbors were replaced with government agents sent to spy on him, as well as the cashiers at stores he frequented He started taking their pictures. When they expressed disapproval, this reinforced their guilt, in Yates' mind.

He saw spies everywhere. While driving, he saw middle-aged white men pull up next to him and stare. While taking classes at Pima Community College, young, white women who spoke with him were also spies. He also thought they were in the KKK and sending him subliminal messages.

He said they were poisoning him via Papa John's Pizza, which had prompted him to go to the hospital in March, carrying a Powerade bottle filled with his own urine, asking it be tested for arsenic.

In April, Yates wrote a letter to a judge involved in his pending case: "I'm writing this letter to you because I'm concerned for my life," he wrote. "Due to the felonies that are involved in my case, the United States government has been trying to kill me."

On May 4, Yates didn't show up to court, and the judge issued a warrant for his arrest. Three days later, he dropped Cassandra off at the hospital. She had a stab wound in her neck.

She told police she'd been sleeping in her car and woke up to a stabbing pain. Yates was in the driver's seat, knife in his hand. She remembered him saying, "You tried to set me up, and you tried to kill me." She begged him to hide the knife and take her to the hospital.

After her wound was bandaged, Cassandra told police her husband had been acting crazy for a year. She said he had been petitioned to Kino Hospital, where the Crisis Response Center said they wouldn't release him until he was medicated but that the hospital staff didn't follow through.

Two days later Cassandra called them, backing away from her original statement with a claim she remembered new details: Yates had been cutting something and his hand slipped, slicing her neck. It was an accident, she said. Yates was never charged.

The Sheriff's Department did look for Yates after this incident, including going to the homes of family members, but they were unable to locate him.

He was arrested for the bench warrant in June, and the courts proceeded with the mental examination. Dr. Michael Christiansen evaluated Yates and diagnosed him with Bipolar I Disorder vs Schizoaffective Disorder with Narcissistic personality traits. The courts ordered Yates to take 700 mg of Seroquel to control psychosis. Christiansen said the medication was "essential in sustaining competency to stand trial."

Yates pled not guilty to the felony charges for drug sales and possession of a firearm. At his request, he switch public defenders several times and was denied the request to represent himself.

In September 2016, after almost 15 months in jail and one mistrial, a jury of his peers found Yates not guilty of all charges, and he was released.

Two months later, on the evening of Nov. 20, Yates and Cassandra went to a friend's apartment on the east side.

The friend got a call and went into her bedroom, leaving them in the kitchen. She heard a bang that sounded like a balloon popping. She ended her call and listened at the bedroom door before she opened it and was face to face with Yates. When she started to walk into the hall, he said she might not want to.

Cassandra was lying on the floor. There was blood on her head. The friend asked Yates if he had hit her. Then she saw blood under Cassandra and the gun in Yates' hand.

"Do you know how long she's been trying to kill me?" Yates asked the friend, wiping down the gun, according to her statement to police. She added that he wiped down other things he'd touched. He took her phone and deleted content from when he'd used it earlier.

She asked him to leave and called the police. Police apprehended Yates early the next morning, sleeping in a vacant apartment down the street. They brought him to Pima County Jail, where he would eventually end up in a cell with Roth.

On the morning of Roth's murder, an officer at the Pima County Jail called in sick. The corrections officer on duty, J. Montreal, would have to keep watch over twice as many inmates.

Jail policy states that two housing units, or pods, may be monitored by one officer, making rounds that don't exceed 30 minutes. Montreal "conducted his regular rounds to check on inmates as close as possible to that time frame due to all the other tasks he had to perform between pods," according to the sheriff's department incident report.

Apart from his rounds, Montreal had to prepare nine inmates for a trip to the medical unit. He opened their cells, gathered them in the day room and pat searched them. He brought them to the sally port, for transfer to the medical unit then prepared their lunches.

When he returned to the cells, he looked into cell 24 and saw a bloodied Roth lying on the floor.

I want to show you guys how much I appreciate all you have done for me. I love you guys. Never forget that... I hope you guys can forgive me.

—Roth's 2015 letters to his parents

Osment found out about Roth's death two weeks later, on the news. She immediately found Carrie on social media.

Carrie had already been stalking Osment's Facebook page, pouring over pictures of a baby identical to photos that filled the pages of Roth's baby book—same face, same expressions, same little pointy ear.

This Christmas, Carrie and Rodney stayed in, just the two of them. They opened gifts and watched Christmas movies. She made her grandmother's omelet recipe: green pepper, onion, milk and sugar.

They celebrated with their grandson two days earlier. At nine months old, he was too busy with his fire truck to pay attention to their adorned little tree, piled with ornaments and strands of shiny beads.

Rodney had planned to adopt Roth this Christmas and give him the last name Walker.

"They took that all away from me," he says. "With time, it doesn't really get better. We just learn to live with it."

They spend a lot of time with their grandson. Osment brings him over on weekends, and sometimes he spends the night. Carrie plays with him. Rodney makes fun of him. And the baby with his father's smiling eyes laughs at it all.

After Roth died, Carrie went to the funeral home. They wouldn't let her see his body. The mortician told her there was a mark on his neck.

"Then I read the autopsy report, and I was glad I didn't see him—for that to be my last memory of my son," she says. "People like Yates live forever. They do. People like Branden apparently don't."

In November, Carrie filed an $11 million claim against the county.

"I don't know who I blame more, if I blame the Sheriff's department or I blame Yates," Carrie says. "I know for a fact his death was preventable. No one can ever tell me different."

At the time of Roth's murder, the jail was only giving Yates 225 mg of Seroquel, although a year and a half earlier, the doctor who evaluated him said 700 mg of Seroquel was essential in order for Yates' to maintain competency to stand trial.

The day after Roth's death, jail staff increased Yates' medication to 400 mg.

Medication and dosages of inmates at the jail are determined by medical professionals with the outside healthcare agency Correct Care Solutions. Jim Cheney, spokesman for the agency, said CCS "takes into consideration any and all valid and available records related to a patient's medical history" when deciding dosage. He wouldn't comment as to why an inmate might receive less than what previously court-ordered to take.

Carrie's furious her son was in a cell with Yates—a man with murder charges and a documented history of violence.

Cellmates are chosen based on inmates' level of risk. There are five risk levels: minimum, low, medium, close and maximum. The minimum level is for low-risk inmates who have already been sentenced and are held at a minimum security facility. The low, medium and close levels are kept together in general population without segregation or restrictions. The maximum-level inmates are kept separate.

Corrections specialist consider a number of factors including current charges, prior convictions, institutional behavior and prison gang affiliation, according to Corrections Bureau documents. They compile factors with a risk assessment classification system, with inmates' risk gauged on a number scale ranging from zero to 300+, with the levels having some overlap. The low custody level is zero to 90, medium is 80 to 125 and close is 100 to 260.

Roth scored a 95. He would have fallen into the medium level because of having a prior conviction. Yates scored a 130, putting him in the close level, the highest allowed in the general population. Housing people together with such a risk disparity is not uncommon.

"There is no perfect scenario for breaking everybody up and housing them—everybody in their own spot," said Corrections Chief Byron Gwaltney during an interview in April. "There's very limited amount of space we have where people are kept in single-person rooms."

Gwaltney also said it's not practical to consider Yates' prior history of domestic abuse with Cassandra when classifying—in part, because the information is not in the database they use.

Before Roth, the last death at the jail as a result of inmate-on-inmate violence was about 41 years ago. They haven't changed anything about how they classify inmates' risk level or house them since Roth's death, according to Gwaltney.

The jail did do an internal review comparing their system with other facilities and found theirs was "consistent with best practices," he said. The jail is in the process of a full audit of the inmate classification system, with an outside agency and will get the results soon.

A good majority of the good memories are in our heads and that is something I will always remember. Like do you remember when I was little and grandma and grandpa would have a big old box for me. And I would get in the box... Those are the things that can't be taken away from us...

—Roth's 2015 letters to his parents

After Carrie's dad died, she drove up Mount Lemmon with three bags of ashes: her dad and his two dogs who'd died before him.

She parked her truck at a pull off and walked into a canyon. She opened the three bags and mixed the ashes together. Leaning over the cliff edge, looking out over Tucson, she let the ashes fall into the wind.

She says Roth's death will feel real when the case finally goes to trial—when she's sitting in the courtroom with Yates and hearing the details of her son's final moments.

"In court, when I see my son's body on the autopsy table, the crime scene pictures, Branden in the cell and all the blood—yeah, I know it's coming," she says. She looks at Rodney and adds, "and he's going to be there to catch me."

When his death feels real, Carrie will take Roth's ashes, along with his dogs' Bonnie and Clyde. She'll drive them up to the lookout she calls "her dad's view." And she'll let her son go.

I don't know how to thank you for being here for me. After everything that has happened, I greatly appreciate it. You have no idea how much it means to me knowing I have your positive encouragement and the love behind it too. It means a great deal that you're still standing by my side. Love, your grateful son, Branden Roth.