"I need you, Steve," Walkup told him.

A local transit booster, Farley wasn't persuaded by the mayor's pitch. Instead, he helped organize a political committee, Citizens for a Sensible Transportation Solution, that started a petition drive to put a transit-heavy plan on the ballot. Farley's group was one of several that opposed Walkup's proposition, which was rejected by about 70 percent of the voters.

So it was hardly surprising that Walkup wasn't in the mood to help when Farley and other members of Citizens for a Sensible Transportation Solution needed a hand. This summer, as the deadline to turn in signatures approached, attorneys Joy Herr-Cardillo and Clague Van Slyke III asked the City Council to bypass the petition process and put the plan directly on the ballot. Walkup, Democrat Shirley Scott and Republicans Fred Ronstadt and Kathleen Dunbar turned down the request.

A few weeks later, when Farley and his crew were weighing legal action after City Clerk Kathleen Detrick began striking signatures from the petitions, Walkup and the Republicans abruptly reversed course and voted to put the question on the ballot. The only council member to object was Scott, who stuck to her original vote.

It was a deft ploy by the Republicans. By placing the transportation plan before voters, Walkup neatly defused a potential political backlash from initiative supporters. He managed to shift the focus of the transportation debate from his own recent failed plan to the light rail issue. And, perhaps most advantageous, he put a wedge issue on the ballot that homebuilders and related Growth Lobby groups are now using to club his Democratic opponent, Tom Volgy, as well his fiercest critic on the council, Democrat José Ibarra.

In short, it looks like Steve Farley might be helping Bob Walkup after all.

A GRAPHIC ARTIST who created the popular photographic tiles on the Broadway underpass just east of downtown, Farley is a true believer in his public transit crusade.

Farley is not a one-man show; he's had widespread help from Van Slyke, Herr-Cardillo, physician Ron Sparks and a long list of fellow travelers who believe that if you build a better transit system, the people of Tucson will ride it. The plan's supporters include Congressman Raúl Grijalva, Pima County Supervisor Richard Elias, Tucson City Council members Carol West and Steve Leal, and the local Sierra Club chapter.

But Farley is probably the most recognizable spokesperson for the propositions. (Voters will see two questions on the ballot; Prop 200 amends the city charter to raise the sales and construction taxes, while Prop 201 lays out the plan.) He talks about the plan in the media, organizes neighborhood canvasses and sends a weekly e-mail bulletin updating supporters on the campaign.

Farley sees light rail as the centerpiece of an improved public transit system because it's a "sexy" alternative to buses. He points to other Southwestern cities--Phoenix, Albuquerque, Salt Lake City, Denver and Dallas--that have already built or are building light rail systems. In those cities, light rail has been a hit among people who had never before considered using public transit.

But the transportation propositions contain more than just light rail, which accounts for 22 percent of the spending. Another 20 percent will be spent repairing Tucson's crumbling neighborhood streets, while the biggest chunk of money, some 40 percent, will be spent on improving the bus system by extending hours of operation and the boundaries of the system, as well as making waits at bus stops shorter. Other money will be spent on sidewalks, bike paths, increased traffic enforcement and the downtown trolley. (See "Details, Details," Page 18)

Most of those elements are popular with city residents, according to recent public surveys. Tucsonans complain about dangerous drivers and frequently put a better bus system near the top of their transportation priorities, even if few of them embrace the current Sun Tran service. Transportation department staffers say the city's residential streets have been woefully neglected. (See "Political Pile-Up," Page 17)

Volgy says he supports the proposition because it begins to address some of the projects included in the Pima Association of Government's 25-year transportation plan, but he makes a point of adding that it only provides part of the solution for Tucson's transportation woes.

"If I would have written the initiative, I would have written it differently," Volgy says. "I would have written it more comprehensively."

Even though Walkup voted to put the question before voters, he opposes the plan because, he argues, it focuses on the wrong priorities. Although he said during the city's sales tax campaign that he supported light rail in Tucson's future, he's now arguing that it's an outmoded system and that buses are a better investment.

Walkup hasn't hammered Volgy on light rail, but then again, he hasn't really had to. He's got two separate campaign committees backed by the Growth Lobby that are working to tear down support for both propositions and the Democratic candidates who support it.

Critics of the proposition, such as Chamber of Commerce director Jack Camper, have focused mostly on the rail element, because they see the idea of train lines down Broadway and South Sixth Avenue as a big leap of faith. They say the costs could rise far above Farley's estimate of $38 million a mile, pointing to the average cost of $60 million a mile for a light rail system in Phoenix.

Farley defends the $38 million estimate, arguing that the plan has been vetted by "national experts" and that other communities have laid light rail for considerably less. He points out that the federal government estimates the average cost of light rail projects is $34.8 million a mile, according to Pima County transportation planners.

When Camper complains that the light rail plan relies on the federal government's willingness to provide about 60 percent of the capital costs of the system at a time of record federal deficits, Farley points to the other Southwestern communities where the feds are helping build light rail systems that riders are embracing.

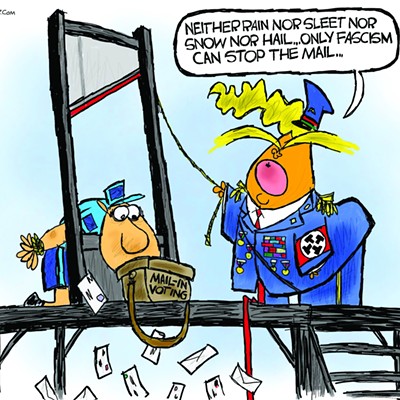

And on it goes, with Farley quick to respond to his critics. But the light rail advocates have one basic problem: getting their message out. Although organizers have put together an energized grass-roots effort, they have little money available for an aggressive campaign. The group has raised $38,506 since it first registered with the city almost two years ago, but most of that money was spent during the petition drive, according to reports filed with the city. As of Aug. 21, the committee was nearly $328 in debt; since then, they've raised just $6,835, mostly in small contributions from little-known Tucsonans. Their biggest campaign expense over that period has not been direct mail or phone banks, but $2,182 on T-shirts.

Even Farley concedes the group is underfunded, but he says he hopes that the group's website, www.savetucson.org, along with an ongoing canvassing effort, media coverage and a publicity pamphlet sent to voters by the city of Tucson will get people informed about the plan. "We often find ourselves relying on the kindness of strangers," Farley says.

Compare that to the primary group that's opposing light rail. The Committee for Real Regional Transportation raised $40,750 between Aug. 31 and Sept. 29, according to campaign finance reports filed last week. (More is undoubtedly on the way.) Most of the funding came from the homebuilding industry, with the Southern Arizona Home Builders Association kicking in $22,500. As an in-kind contribution, Southwest Gas and the Arizona Builder's Alliance spent $10,500 on a survey.

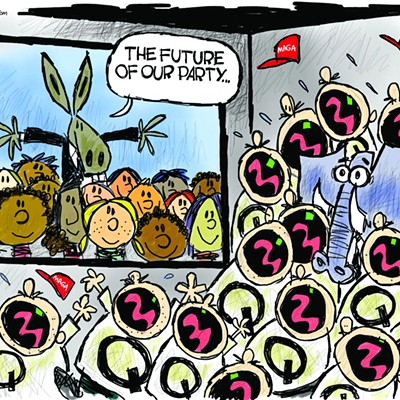

A second independent campaign committee, Independent People Like You, has targeted Volgy and Ward 1's Ibarra, who is facing a challenge from Republican Armando Rios Jr. The campaign committee has dropped several negative hits against Volgy into local mailboxes and put up billboards battering Ibarra for his poor attendance record at city meetings. But a major thrust of the campaign uses outdoor advertising, radio spots and even a mobile billboard driving up and down Broadway Boulevard to club the Democratic candidates for supporting the transportation propositions.

Independent People Like You reported raising $42,290. The biggest checks have come primarily from car dealers andthe folks in the development industry, many of whom don't even live in the city limits. A total of $5,540 came from Jim Click and his family members; another $2,850 was delivered by land speculator Don Diamond and his family members and employees. Other contributors include developer David Mehl and his wife, Bonnie ($3,000), developer Bill Estes ($1,500), auto dealer Don Mackey ($1,000), Tucson Realty president Hank Amos ($1,000) and Long Realty honcho Stephen Quinlan ($3,000). Mortgage broker Dick Dunbar, husband of Ward 3 City Councilwoman Kathleen Dunbar, kicked in $500.

Light rail advocates say money doesn't always win the day in politics; they point to the city's last transportation proposition, which they defeated despite being outspent more than 10 to 1.

But that exception proves another political rule: It is easier to destroy than to create. Convincing people to vote against a tax increase has always been easier than persuading them to support one. Pima County voters rejected sales tax increases for transportation in 1986 and 1990, and city voters rejected the 2002 prop. (They also rejected a 1994 proposition to raise the sales tax by a quarter-cent to pay for a new jail.) The only sales tax to pass in Pima County was a statewide .6-cent boost for education in 2000--and that barely squeaked by.

The unpopularity of sales taxes explains why the Independent People committee wants to link Volgy and Ibarra to the light rail plan. By painting them as out-of-touch politicians who want to raise taxes to pay for an impractical plan, the political operatives hope to duplicate the conditions that led to Walkup's victory in 1999, when he rode the opposition to an unpopular CAP water initiative to victory over Democrat Molly McKasson.

Volgy, who has condemned the independent campaign committees for undermining Tucson's publicly funded campaign system, says he was aware of the political risk involved in endorsing the initiative, but he felt he had to support it.

"It would be utterly hypocritically to oppose an initiative that begins to address some of these problems for brief political gain, and I'm not going to do that," he says. "We gotta get started someplace."