Their dusty clothes, baseball caps and back packs--the unofficial uniform of the illegal border crosser--were dead giveaways of their status. At the moment, though, they were ambling up the avenida on their way to a free lunch offered by Grupo Beto, a Mexican border agency. Suddenly, they noticed some colorful metal figures welded onto the towering border wall.

Two of the men stopped and laughed, pointing at a painted, cut-aluminum sculpture of a green-skinned Border Patrol agent chasing some migrants with a big stick, and another one of a migrant returning home to Mexico with an American washing machine loaded onto his back.

But they weren't worried, they said, about the more serious sculptures, the ones that warned of the dangers in the desert: the saguaro growing out of a cluster of skulls, the fiery desert curling like a rattler underfoot, Mexicans carrying home the body of a dead compañero in a shroud.

"I've crossed a lot of times," boasted José-Antonio Hernandez, a stocky 37-year-old in a Philly cap, speaking in Spanish. "I've lived in L.A., Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Reno. I save money, and then I go home to Vera Cruz. I always cross through the city. I don't worry about the desert."

His young companion, 18-year-old Ricardo Arellano, of Mexico City, was equally sanguine. He was a runaway, he said with a smile, and his parents had no idea where he was. He'd never crossed the line before, in either city or desert, but he was looking forward to the trip--and maybe even to the cat-and-mouse games migrants play with la Migra, the U.S. Border Patrol.

"It's an adventure," he said.

The metal wall Arellano and Hernandez will have to cross on that adventure--unless they strike out into the open, dangerous desert--is an ugly wound cutting some three miles across Nogales. Set into graffiti-scarred concrete and rising up at least 15 feet into the sky, it clings to the landscape, snaking up the town's hills and curving down again into the flatlands. Built by the Americans, the wire mesh at the top tilts into Mexico, the better to deter enterprising climbers. Sky-high cameras stand watch, equipped with night-vision technology that turns night to day, detecting bodies moving through the midnight brush. Seated in white SUVs parked at intervals along the fence are Border Patrol agents, staring down into Mexico.

The wall is military surplus, made of corrugated helicopter landing pads that U.S. troops once laid out in Vietnam's jungles and in Kuwait's deserts. The color of an ugly bruise, its sickly green merges with gun-metal gray. The perfect canvas, in other words, for a giant piece of political art.

"The U.S. put the wall up without discussion," says muralist Alberto Morackis, one of three artists who created "Paseo de Humanidad (Parade of Humanity)," the work featuring 19 human figures and 16 giant milagros that has sprawled along the wall since March. "Our government said, here you don't need a permit to hang art on the wall. In the United States, you have to ask the Border Patrol. Here, there are no rules."

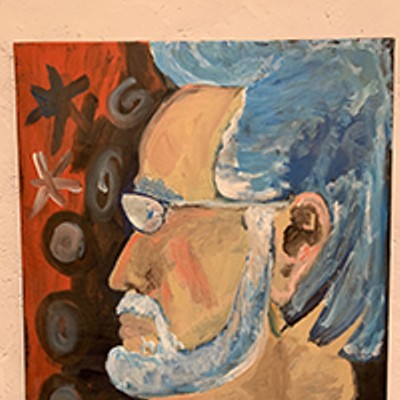

Besides Morackis, a 41-year-old native of Nogales, Sonora, the work's creators include his longtime mural partner Guadalupe Serrano, a 32-year-old originally from Sinaloa, and Alfred Quiróz, 60, a well-known Tucson painter and UA art professor whose specialty is painting searing indictments of injustices of all kinds. Working recently in his South Tucson studio, strewn with leftover pieces of aluminum from "Paseo," Quiróz said the ever-increasing border deaths are ample justification for the art on the wall.

"Too many people are dying for economic reasons," Quiróz said. "Families are being split up because of economic conditions. It's not just the United States' fault, or Mexico's. It's a collaboration."

The deaths of migrants in Arizona's deserts--from exposure, dehydration, hypothermia, car accidents--have increased with alarming regularity every year since 1998, when the Border Patrol put Operation Safeguard into place in its Tucson sector. The agency intensified surveillance and erected walls in Douglas, Naco and Nogales, with the idea of making it harder for migrants to cross at cities. The urban crackdown pushed migrants into the remote deserts, and mortality rates spiked.

Last fiscal year, from Oct. 1, 2002, to Sept. 30, 2003, the number of deaths hit 139, according to Andy Adame, Border Patrol spokesperson for the Tucson sector. This year, even before the searing summer heat, the numbers are already heading into record levels, with 34 dead since October. And that's only counting the bodies the Border Patrol has found.

Gregory Sale, director of visual arts for the Arizona Commission on the Arts, which helped fund "Paseo de Humanidad," said the number of grant applications from artists wanting to do border-related art has paralleled the rising deaths.

"We are seeing more and more applicants coming in with border projects," he said. "(The deaths) add to the urgency of artists wanting to have a community dialogue on border issues."

In Phoenix last month, the Arizona Coalition of Latin American Artists created a portable border fence called "The Mending Wall." They used it to bisect the campus at ASU West during a border conference. It rose again in downtown Phoenix May 7, on art walk night.

InSITE, a private nonprofit in San Diego, stages a bi-annual extravaganza of public art along the border fence with Tijuana, and last year, even Nogales featured another piece, pre-"Paseo," also by Morackis and Serrano. But as the artists and their funders are finding, public political art is not an easy sell. However, with what's at stake, they're determined to keep making it.

"Art is part of the discussion," Morackis declared. "The border is an issue that art can say a lot about."

Morackis' "discussion" and Sale's "dialogue" suggest genteel conversation, but "Paseo de Humanidad" is hardly polite. With its fierce coyotes, flaming hearts, a running leg and a truck stuffed with skulls, it shrieks out warnings to travelers who know nothing of the journey ahead. And it rages that uncompassionate capitalism is the culprit forcing human beings to make the treacherous passage across borders. With NAFTA dumping cheap American corn into Mexico, displaced Mexican laborers come here to work for the lowest wages America is willing to dole out. Morackis and Serrano have painted a retail bar code onto a saguaro, emblematic of an America where everything is for sale. Quiróz gets more literal with a giant flying dollar sign and--even more to the point, when you consider what illegal workers can make--a cent sign.

Attached to a portable metal frame that's welded to the wall, the big piece draws on multiple artistic sources. Quiróz's shiny aluminum milagros, flanking Morackis' and Serrano's painted human figures, take their form from the popular metal religious icons whose name means "miracle." The Mexican devout use these small metal pieces when they pray, strengthening their petition for a cure from heart disease, for example, by clutching a heart-shaped milagro. An ordinary milagro can be cupped in a hand, but Quiróz's are writ large, 4 feet by 6 feet.

"I utilize the religious element, not because I'm particularly religious, but because these icons are something to save us," Quiróz said. "I use the milagros to tell the story of the border."

They're meant to be read in sequence. One set begins with a flaming heart, a conflagration that sends the wanderer away from home. Next is a snarling coyote head, a stand-in for the human coyotes who smuggle migrants across the border for a fee. Then there's a big leg, another traditional milagro icon, but this one is equipped with border-crossing jeans and a sneaker. And it's running. Ahead are a truck laden with skulls, two gallon-size water bottles lying uselessly next to a skull in a now equally useless hat, and finally, the trio of skulls lying at the foot of a saguaro.

If Quiróz's milagros are static warnings about desert perils and capitalist greed, the two Mexican artists have created a traveling pageant of humanity, reminiscent of the "dance of death" in medieval paintings. In those old works, humans from all walks of life cavorted hand-in-hand as they were led inevitably into death; "Paseo" updates this theme to the disorder along the border.

The artists' imagery, Morackis said, combines Aztec iconography with a contemporary sensibility. The stripped-down visuals of modern life--the male and female symbols on the doors of public bathrooms, the stylized footprints from the floor of a bank--shape the figures, making them universal icons rather than individuals.

"We decided to start with the concept of Aztec codices," Morackis said. "The Aztecs didn't have a phonetic language--symbols and ideograms made the letters. We studied those, and we made a mixture of contemporary art and Aztec."

At the far left end of the three groups of figures is a red revolving door, just like the one up the street at the port of entry. Metaphorically and literally, "the border is a revolving door," Morackis noted. "The boys," as he invariably calls the migrants in his enthusiastic English, "bring their labor to the United States as well as their culture." The artwork's figures headed al norte carry a Virgin of Guadalupe and mariachi instruments, while those returning home bear the body in the shroud and American commercial goods, like that washing machine. Above them is a map of a much larger Mexico, what it looked like before the United States won (in the Mexican-American War) and bought (via the Gadsden Purchase) much of its territory.

The central section represents the journey in the desert, where the flaming desert floor is what Morackis calls a "camino with fire." One woman, holding a child by the hand, is giving birth to another, her belly exploding with light. A coyote's chest is painted with the image of Malverde, a kind of Robin Hood figure who has become patron saint to the people smugglers. At the far right, the Border Patrol agent gives chase. His chest is made of the same corrugated metal as the border wall, and he has a voice bubble like those in the cartoons--but he's spouting Latin, which, as far as the people he's pursuing are concerned, is what English might as well be.

Above it all is a blazing sun, wearing the death mask of the Aztec gods.

"It's a way for the migrants to see the dangers that are behind the wall in the desert," the soft-spoken Serrano said in Spanish. "Does it work? Who knows?"

Paseo de Humanidad" is not Serrano's and Morackis' first piece of art on the border barricade. Last year, they attracted widespread attention in Mexico and the United States for "Border Dynamics," a set of four monumental human figures that leaned against the wall in the same location. The piece traveled to the UA last fall, and stood outside the student union--complete with an improvised border wall--for two months.

The 14-foot painted metal figures extended outward from the fence, with their feet in the Mexican soil and only their hands or backs touching the corrugated metal. The message was ambiguous. Either they were trying to push the wall down, climb over it, or keep back the hordes on the other side.

The uncertain fate of "Border Dynamics" is instructive about the pitfalls of political border art. Now in storage, it never took its planned place on the Arizona side of the border wall. Unlike "Paseo," which got just shy of $5,000 in public funding from the Arizona Commission on the Arts, "Border Dynamics" was primarily commissioned by a then-fledgling nonprofit called Beyond Borders Binational Art Foundation, run by a Tucson husband and wife, Tom Whittingslow and Michaela von Schatzberg.

"We promote border art," Whittingslow said proudly one recent afternoon in his Tucson home. "We commission it. And we create awareness."

A former PR guy, Whittingslow knew about the thriving border art program at Tijuana/San Diego. With installations scheduled every two years on the Baja/California border, InSITE has become an international success, attracting name artists and a sophisticated art audience. Why not do something similar in sleepy Ambos Nogales?

The couple presented their idea in a white paper to the Nogales-Santa Cruz County Tourism Commission. Everybody raved about it, Whittingslow said, but their enthusiasm didn't extend to cash contributions. ("They loved our ideas. Then they all went home.") He and von Schatzberg decided to proceed anyway, and sent out a call to artists on both sides of the border.

"We were looking for contemporary art that was intellectually challenging and that dealt with border, migration and culture. Not Father Kino or the Virgin of Guadalupe," said Whittingslow.

They were blown away by Morackis and Serrano's stark proposal. The two muralists already had 20 to 25 murals to their credit, mostly in Nogales, Sonora, with a couple in Hermosillo and Queretero. They operate as Taller Yonke, Junk Studio.

"There are a lot of junkyards in Nogales," Morackis deadpanned. "And Mexico is the junkyard of the United States." Both artists are self-taught, but while Morackis devotes himself entirely to art, Serrano still labors in a maquiladora, recycling computer parts to support his wife and two children.

The Yonke artists didn't want to do yet another mural. They would create giant metal humans, their flesh painted to look like raw meat. These figures would first lean on the wall in Nogales, Sonora, and try out the wall al norte, in Nogales, Arizona. In a different geographic and political context, the meaning would change. The push on the Mexican side might look like resistance to migration on the American.

Whittingslow and von Schatzberg sought permission from the Border Patrol to set up the "Border Dynamics" figures on the U.S. side. And at first, back in 2002, they got it, they said.

"The Border Patrol was driving me around, helping me pick out a site," von Schatzberg remembered. "We came up with a site at the end of a street, on the east side of the port of entry. All was set. And then it went down."

The Border Patrol suddenly nixed the plan, the couple said, by setting so many conditions that the installation become impossible.

Border Patrol spokesperson Adame said the agency considers art proposals on a case-by-case basis, and that the agency's concerns about "Border Dynamics" centered on security and safety. Beyond Borders, Adame added, would have had to post a guard 24 hours a day and light the installation at night.

"We wouldn't want undocumented aliens jumping the fence and then shimmying down the sculptures," Adame said. "And kids are always playing in the street. The last thing we want is for somebody to get injured."

But Whittingslow blames politics.

"It was too controversial," he said.

Added Sale, of the Arizona Commission on the Arts, "It was a nice project; it had integrity, and it addressed social issues that are part of international dialogue." But with security fears rampant, he said, especially along the border, "it's way more difficult, post-Sept. 11" to do political art.

If political wrangling put the kibosh on a precedent-setting exhibition on the wall stateside, the other problems the project faced were financial. The commission awarded Beyond Borders a small grant of $1,400. Whittingslow and von Schatzberg raised some other money privately, but they also had to dip into their own funds.

"I would sell a freelance story," said Whittingslow, who works as a writer, "and I'd give the artists some money. We scraped together $5,000."

The sculpture debuted to a media frenzy in Mexico in January 2003, with the "Border Patrol all up on the other side, watching," according to Whittingslow. In September, the artists brought the piece to the UA, with a little financial help from Wells Fargo Bank to erect a makeshift border wall.

But there's no money left for the projected grand tour of the United States. Whittingslow and von Schatzberg are still hoping that a visit to Vanderbilt University this fall will materialize. In the meantime, "Border Dynamics" languishes in a storage shed.

They're also uncertain whether other projects will fly.

"We were going to pick an artist every year," Whittingslow lamented.

They had lined up Louis Hock, a star of the border arts movement with Arizona roots. Now a professor at UC-San Diego, Hock and some partner artists once triggered a furor by converting an NEA grant into fresh $10 bills and handing the money out to migrants successfully arrived on U.S. soil, in honor of their contributions to the American economy. For Beyond Borders, Hock was to team up with some journalists to create "Tener Sed" (To Be Thirsty), a "mixed-media memorial to migrants who died of thirst on the U.S.-Mexico border," according to an application to the Arizona Commission on the Arts.

The plan was to exhibit the work at the DeConcini Port of Entry in Nogales, and then bring it to the University of Arizona Museum of Art. But it hit a snag when the UAMA director abruptly decided not to renew the contract of chief curator Peter Briggs, who had been working with Beyond Borders. Reached at the museum, Briggs said he had been tentatively planning on a 2005 exhibition date for the Hock installation. Now that he is being forced to leave the museum June 30, "I don't know whether it will happen or not," he said.

Sale said the Arizona Commission on the Arts still plans to give Tener Sed a little money ($1,575), but it's only a small portion of the costs. A discouraged Whittingslow will say only that the project "awaits funding." Despite all the troubles, he still thinks hard-driving border art has a future in Arizona.

"I think this is going to grow," Whittingslow said. "It's too good an idea to just go away."

The creators of "Paseo de Humanidad" know all about funding issues for border art. Most of the grant money they got went toward materials. Quiróz said each of the three made just $500 for their months-long labor on the sculpture. And as with "Border Dynamics," they had planned a grand tour for the new piece, with visits projected to each of the Mexican border cities hemmed in by walls. Right now, they're awaiting money from an organization in Hermosillo to take it at least to Agua Prieta, and they're making a pitch to the Arizona-Mexico Commission in June.

"We have to convince both sides why this exhibit must keep running," Morackis said.

Until and if the cash materializes, "Paseo" will likely remain on the wall in Nogales. Meantime, Morackis is preparing for a summer mural commission from the city of Nogales; Serrano is back on the line in his maquiladora; outsider artists continue scrawling anti-U.S. graffiti on the hated border wall; and the migrants just keep coming.

The same day Hernandez and Arellano and dozens of others passed it on their journey into the U.S., Nogales resident Noel Gonzalez and his son, Noel-Fernando, stopped to admire it.

"I like it; it's well-designed," Gonzalez said. "It's about the dangers in the desert. It's hard; they don't find water. It's about death."