Each year in February, multinational merrymakers throng the streets of Laredo to celebrate the birth of the father of the nation. Musicians play their accordions and violins in the patriotic parade, crossing the bridge from Mexico to jostle shoulders with the progeny of Texas ranchers, who toot their trumpets in high school marching bands.

The Rio Grande trickles past this South Texas border city, dividing American Laredo from Mexican Nuevo Laredo. But for one day a year, at least in the old days, the border was suspended, its guardians furloughed.

"When I was a kid, the bridge was open," says Laredo native Martínez, "and people walked back and forth all day."

Two worthy citizens are still selected each year to portray George and Martha and, more often than not, Martínez says, these "positions of honor" go to Mexicans, who duly dress up in powdered wigs and Revolutionary War garb.

"It's a very Mexican-American town. Even Anglos speak Spanish. It's always practical to speak Spanish there." And, he adds in an understatement, "It's a very unique cultural place. "

Martínez brings his distinctive Laredo vision to the Tucson Museum of Art a week from now, when he opens a show of his Vatos paintings on Saturday, July 22.

"My work deals with a mixture of cultures, a mestizo culture," he says. His oils on canvas and paper conjure up vatos and pachucos, the "cool guys and dudes" Martínez remembers slouching down his hometown streets back in the '40s, '50s and '60s, when he was a kid. (He was born in 1944.)

"They're not really portraits of individuals," he explains by phone from San Antonio, the South Texas city 150 miles northeast of Laredo where he's lived since 1971. "They're more like characters based on real people. I'm trying to portray the flavor of an era."

Martínez's solo show is the fifth in a yearlong series at the Tucson Museum of Art celebrating Hispanic artists whose work, like his, depends on their "living close to the border." The series, Vistas of the Frontera--a deliberately bilingual title that translates as "visions of the border"--was organized by Stephen Vollmer, the curator of the art of the Americas who left the museum at the end of June.

"The border has always been this really wonderful, nebulous area," Vollmer says in his dismantled office on his last day at work. The exhibitions "jump stereotypes, and go beyond this idea that the border is (only) about Arizona and Sonora." The six artists "are of both genders, and various ages and regions, from Texas to California."

At least five of them grew up in what Vollmer calls the "pollinated hybrid culture" of the U.S.-Mexico border, a "distinct cultural zone" that stretches 150 miles into each country. (A sixth, Claudia Bernardi, is Argentine.) As children, most of the Vistas artists lived a short distance from the international line, and their peripatetic lives demonstrate how fluid the border once was.

Adriana Yadira Gallego, a UA-trained painter whose solo show is up through this Sunday, was born in Sonoran Nogales, grew up on the Arizona side and routinely crossed over to visit family. She's now moved on to Los Angeles. Anna Jaquez, whose installation work goes on view in September, has lived most of her life in El Paso, but her mother was born in Arizona and raised in Ciudad Juarez, across the Rio Grande from El Paso. And Tucsonan Juan Enriquez, whose prints and paintings kicked off the Vistas series last winner, was conceived in Mexico, born in the United States in 1974 and spent his childhood in a succession of Southern Arizona mining towns.

"The border is a channeling area where people migrate back and forth," says Enriquez, a UA grad who helped found Tucson's Raices Taller 222 gallery, a co-op for Hispanic artists. "It's a sharing of ideas and genders, rural people coming in to work with city people. Amazing things are coming out of it. We don't even know it all yet."

Vollmer says he hopes the artists' work conveys a more complex picture of the border than Americans normally get in their "newspapers and rag mags." Far from being a hard line where Yankee English abruptly stops and Mexican Spanish begins, the border cultural zone is every bit as cross-culturally rich as Laredo's Washington's Birthday parade, a fertile place of "many traditions and extractions and heritage," he says.

Vollmer himself was raised in San Antonio, the son of a German-speaking father and a French-speaking mother. Since the 1840s, he says, South Texas has had "one of the largest concentrations of central Europeans in the U.S."

If such facts startle, so does the artwork he chose. The Vistas artists often use conventional media, from oils to acrylics to inks. But they also draw on the materials of Mexican folk arts, urban and otherwise. Gaspar Enriquez, who was the spring artist, abandoned oils and brushes years ago for the smooth blast of the airbrush. A schoolteacher for 33 years, he conjures up portraits of the gang bangers he taught in El Paso's Segundo Barrio, picturing them in confrontational art inspired by painted low-riders.

Jaquez originally trained as a jewelry artist, but now she welds her metals into tiny domestic interiors evoking the lives of Chicana women, and drenches everything in the hot colors of Mexican paper flowers. Juan Enriquez has carved at least one print into rubberized mats his dad brought home from the mines. Printed on paper in stark black and white, his "La Llorona" pictures the fearful wailing woman of traditional borderlands lore next to a contemporary barbed wire border fence.

All of the artists unapologetically portray their own culture. Martínez's Vatos, the painter says, are "a form of cultural documentation: I've never seen guys like those in paintings before."

Martínez and Gaspar Enriquez were both close friends of Luis Jiménez, the internationally known Chicano artist who died tragically in a studio accident last month, and they point to his influence.

"Luis was a role model," Enriquez says. "He led the way. He started out doing pop art but then started going back to his roots and doing his Chicano art as well. He paved the way for a lot of us."

The exhibitions are not meant to be explicitly political--the border, Vollmer says, readily serves as metaphor for personal frontiers and challenges--but it's impossible not to see them in the context of the current furor over illegal immigrants. Some of the artworks, like Juan Enriquez's "La Llorona" or Gallego's paintings of hands delicately entwined with barbed wire, seem to scream in anguish over the unfolding tragedy of deaths in the desert. But the artists don't necessarily offer any solutions to the vexed problem of immigration.

"If I had the solution, I'd be in George Bush's cabinet," says Gaspar Enriquez. He lives near the Rio Grande in the Texas hamlet of San Elizario, in the 250-year-old adobe house where his late wife's family lived for generations. Daily he watches migrants hide from the Border Patrol under the bridges in the now-dry riverbed. Despite the "river, canal and chain-link fence," the migrants regularly win the "cat-and-mouse game" with la Migra.

"They're determined to get to a better life," he says. "Putting up a fence is not going to solve anything."

Martínez believes that "some reactions are racist. But some concerns about security are reasonable. But migrants wouldn't be here if there weren't opportunities for bettering their lives."

Gallego learned at close hand what barbed wire can do to a desperate border crosser. Her father, Carlos Gallego, was a firefighter in Nogales, Ariz., retiring as battalion chief. He'd often come home with grisly tales of migrants who left more than empty water bottles behind.

"Dad had to recover fingers from the fence," she says during an interview at a Tucson café shortly after she opened her show. "There were all these different stories of how people got across. Being from the border, I carry that with me. But the border is not the be-all and the end-all of my work."

Gallego was born in Nogales, Sonora, in 1974, but brought as an infant almost immediately to the American side, where her father was a U.S. citizen. The family spoke Spanish at home, though both parents knew English as well, and the two children grew up bilingual. (Her brother, Carlos, now teaches English at the UA.)

But underscoring Vollmer's point, Gallego remembers Nogales as a fertile mix of cultures, of Greeks, Arabs and Koreans, along with the expected Mexican Americans. To her child's eyes, Ambos Nogales, the two cities of Nogales, were like one place, inexplicably divided.

"Both sets of grandparents and my aunts and uncles lived in Sonora," she says. "We had to go through these gates. There was always a sense of intimidation--you were granted access to family only if you had your documentation. As a child, I would ask, 'Why do some people need permission?' Even now when I go through the border, I think about the divisions that keep families apart."

She came to the UA with the intention of going on to law school to fight for human rights, but she discovered art after beginning to doodle in a psych class. It was love at first sight, she remembers, and she decided she could "communicate the same ideas through art." She trained as a painter at the UA under the professors she calls the "dream team": Alfred Quiróz, Bailey Doogan, Chuck Hitner and the late Bruce McGrew.

The works in her TMA show include seven acrylic paintings of hands beautifully drawn and delicately intertwined with barbed wire, and four metaphorical paintings depicting women breaking beyond their limits. The wall texts speak of the "epic journey" of crossing the "expanse of great deserts."

All of the paintings have hands twisted into dancer-like gestures. In "Erosion," a hand is grasping the earth and seems to bleed. In "Devil's Rope," three hands successively twirl their way through coiled barbed wire. Two hands are trapped in a circle of wire in "Checkpoint."

The works partly embody her father's haunting stories of migrants' maimed hands, but "I don't limit it to the portrayal of someone going through barbed wire," she says. She was equally inspired by the Hindu statues of dancers at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, Calif., where she has worked in the education department since last year. The statues' many-armed goddesses clasp and pinch their fingers in the mudras hand gestures of traditional Indian dance.

Painted in pastel blues and peaches ("my L.A. palette," she jokes), the lovely pictures also draw on the Hispanic Catholic imagery of her childhood. They suggest both the meditative prayers counted out on the rosary and the torment inflicted on Jesus by his crown of thorns.

"Barbed wire could be like beads of the rosary," she says. "Meditation helps in these difficult situations."

Much of the political attention now directed at the border, she believes, is a "distraction to get away from other stuff. We have serious economic issues, and they're looking for migrants coming in from Mexico as scapegoats." Her art may not change anything, she says, "but I like to present moments of reflection. Another person can adapt it to their own life. If it makes them angry, even better."

Much of Anna Jaquez's artwork deals with childhood memories good and bad, of her parents' warm kitchen, of a scary cesspool out back, of her grandparents' wisdom, and of her fears of a nuclear holocaust.

Born in 1953, she grew up in a family of six children in El Paso, in the shadow of the Cold War.

"I was afraid of everything," she says by telephone from her home in northeast El Paso. "I spent sleepless nights in my bed shaking. If I heard an ambulance, I would think that war had broken out."

A metal artist who sandblasts copper and then colors it with Prismacolor pencil, Jaquez got a BFA and a master's degree at University of Texas at El Paso, and an MFA at New Mexico State in Las Cruces, 45 miles away.

"I was raised in El Paso and never really left," she says. She now teaches part-time at UTEP.

A major installation piece, "Mexican Elders," will be the highlight of her TMA show, opening in late September. It consists of four paintings on the wall and four constructed tree trunks on the floor; atop each trunk is a tiny metallic diorama re-creating a memory of her family's life. The colors go from the sky blue of dawn to pink to afternoon ocher to nighttime blue, marking out the hours in a day, or a life.

"I have always used a lot of bright colors in my work, because it seems like a natural thing to do when depicting my culture," she says. "Mexico is in so many ways about color even (when) the subject matter is so dark and grim. I feel it is the colors I use that make (my art) so obviously Mexican."

The tree trunks in "Elders" represent "what my grandparents taught, roots and lessons." But on this sturdy base, the tableaux of her childhood fears play out.

The first trunk bears a tiny shark-infested sea, paying homage to scary family trips to Mexico, where her mother was orphaned and struggled to support herself as a teen. The second diorama recalls the alligators that once lived in a pit in a downtown El Paso plaza and terrorized the young Anna (they're now memorialized by Luis Jiménez's "Lagartos" sculpture in the plaza). The third, depicting late afternoon in the family kitchen, is "warm and cozy," she says, "the place for telling stories." But the dark last sculpture inevitably explores her fears of her parents' decline and death. (Her father, a retired railroad worker, died last year.)

But not all of Jaquez's work is so introspective. One piece mourns the unsolved murders of hundreds of young Mexican women in nearby Ciudad Juarez, where they moved from all over Mexico to labor in the maquiladora factories. The little diorama includes an outdoor Mexican market with umbrellas ("the umbrellas symbolize the cover-up of the murders") and a flower shop filled with funeral wreathes bearing banners labled hermana ("sister"), hija ("daughter") and nieta ("granddaughter").

The title "DeOlores" is a Spanish play on words, she says, alluding to the Spanish for smell and pain, and suggesting the popular song "De Colores."

The Juarez murders help confirm some of Jaquez's fears of the world as a dangerous place. A student warned her against taking photographs in the Mexican city, saying the drug dealers in town would find it "not cool," and she has rarely crossed the border in the tense times since Sept. 11.

"People come over here to improve their lives. That's what my parents did," she says. "They wanted a better life for us. I can completely understand. But (open borders) might jeopardize our safety."

César Martínez, who opens his Vatos show next Saturday with a charla--an informal, bilingual talk in the galleries--grew up the only child in a female household.

"My mother was a cashier in a drugstore in Laredo," he says. "My father died before I was a year old of kidney problems. I was raised by my mother, my grandmother and my aunt."

He managed to get himself to college at the old Texas College of Arts and Industries (now Texas A&M-Kingsville) and pick up an art degree before getting drafted in the late '60s. Martínez was sent on a tour of duty, not to Vietnam, but to another contested border, the DMZ in Korea. He was safe, more or less, working as a radioman in a medical battalion, he says, but the Army discharged him early after 18 months of what it called a "hardship tour." On returning home, he moved to San Antonio, the biggest city in South Texas close to the international line.

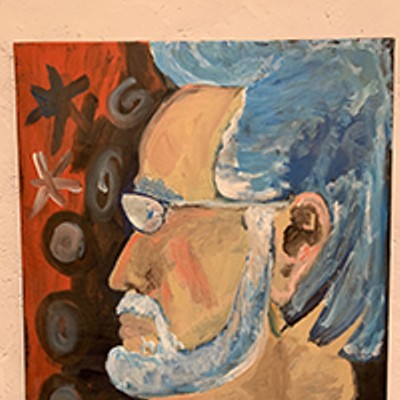

Ever since, he's been making art evoking life in the borderlands. His South Texas series consists of mixed-media landscapes, constructed partly out of old lumber and dirt. His Serapes paintings were inspired by the colors and patterns of traditional Mexican weaving. His most recent work is the portraits of Vatos, young men with attitude, in dark glasses and exaggerated pompadour hairdos, painted against lyrical color backgrounds.

Vollmer sees the Vatos work as a premier example of the border's cross-cultural blend, mixing contemporary mainstream art styles with the vitality of the frontera. The paintings unexpectedly combine the starkness of Richard Avedon's upfront photo portraits with the color field innovations of Mark Rothko, he says.

"The manner in which he moves his paint, his brushwork, his wonderful pastels: It becomes a color field of Rothko. How do you bring Rothko together with Avedon? It's a wonderful perspective. He has shifted the paradigm.

"He creates almost in a medieval sense Everyman and Everywoman, but they represent the Latin Hispanic culture of the border."