Laurel Watkins, 16, Danielle Gimblett, 18, and Kaylee Ducote, 16--the core members of Tucson High Magnet School's Amnesty International chapter--say it's the least they can do for their "sisters" on the other side of the border.

Last month, the bodies of Esmeralda Juarez Alarcón, 16, Violeta Alvidrez Barrios, 18, and Juana Sandoval Reyna, 17, were found in the desert outside Juárez. Their deaths marked the most recent in a string of some 300 murders and kidnappings of young women in the city of 1.3 million since 1993.

Though Mexican police have arrested several men, the crimes have continued. Women's groups and human rights activists claim the investigation is going way too slowly and that the cases currently awaiting trial are fraught with violations of due process. The complications and procrastination, some say, suggest Mexican authorities might even be involved in the murders.

It's no secret that border cities like Juárez are often plagued by chaos. Tucson author Charles Bowden, who chronicles some of that chaos (via the drug trade) in his recent book Down by the River (Simon & Schuster, 2002), said the crimes in Juárez are never solved "because the cops are incompetent and corrupt" and because "a heritage of torture and bribes hardly creates a modern forensic team of investigators." In such a place, he said, "killers of young women walk about with impunity."

Meanwhile, young women walk around in fear.

Many of the murdered women disappeared on their way home from working in the maquiladoras, foreign-owned assembly plants that set up shop on the border after 1964, the year the Mexican government initiated the Border Industrialization Program, providing incentives for them to locate there. The plants drew thousands of workers from throughout the republic to the border, where they have settled in self-help colonias--neighborhoods that often lack basic services such as electricity, water and adequate sewage drainage.

Since their arrival, the maquiladoras have attracted a disproportionate number of young women--the logic being that that their nimble hands could work fast and that they were docile, obedient and unlikely to unionize. Over the years, activists and workers have chipped away at that philosophy and succeeded in improving conditions and wages in some factories. But since the murders began, the daily duty of traveling to and from work through desolate areas has presented the greatest occupational hazard yet.

For years, the Mexican government kept information about the kidnappings and murders from the public. Victims' families and feminist activists on both sides of the border have pressured the authorities to disclose information. More publicity, they hope, will continue to pressure the authorities (the Mexican government with assistance from the United States) to work harder.

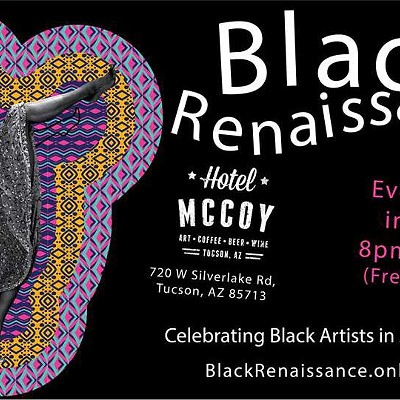

This weekend's art auction, its organizers say, will raise awareness about the crimes and raise funds for Nuestras Hijas Regreso de Casa (Bring Our Daughters Home), a Juárez-based organization comprised primarily of victims' mothers. Formed two years ago, the organization's main purpose is "to demand judicial justice for the unjust death of our daughters," said the group's president Rosario Acosta, speaking from Juárez. Acosta's daughter was murdered in 1997.

Recently, Nuestras Hijas filed a complaint to the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights against the Mexican government for failing to solve the murder crimes.

"Mexico has signed important agreements to uphold human rights here," Acosta said. "They're obligated to comply with them."

Acosta said she was thrilled to learn of the Tucson teenagers' effort to help. Any financial assistance will go toward daily operating expenses such as office rent and "to continue carrying our voices as far as we can," Acosta said.

None of the young Tucson organizers have ever visited Juárez, nor do they peak Spanish. They say they were motivated by their frustration over the lack of justice and because they identify with the victims.

"These women, they're mostly our age," Ducote said. "This is happening very close to us so it hits home."

It's disturbing, they say, that women their age on the other side of the border don't have the same freedom that they do.

"Kaylee [Ducote] and I walk two miles home from school everyday. We feel safe," Watkins said. "We don't want to take that for granted."