I have never belonged.

I've cobbled together a life without a clear idea of a career. Money has been a fuel, not an interest. I've never felt aimless but often careless.

The wind seldom blows at this place and days are almost always sunny. I've never laid eyes on it but I know it is there. There has never been a moment's doubt about its existence. The place is as solid as rock in my mind.

I have never belonged to a place or movement or belief. But still I look. On a bend, I will see it.

I got my suitcase in my hand

Now ain't that a shame.

I live in a time when nations harden into fossils and humans retreat into memoirs. I have never belonged to my time.

For me there are no nations, and families are a thin skin quickly shed once flight from the prison of home became possible. There are two worlds: the living one moving in the day and night through the grass and forests, cruising the rivers, coursing through the seas. The sky, also. And then, there is the world of noise talking money and ideas and patriotism and duties and hundreds of other lies. I am stranded between these two worlds, tugged by the murders and vices of my species and bound by every cell in my body to the stars and dirt and slobbering beasts that live ignored and yet persist.

No meeting of my kind has ever mattered to me as much as a tree on the hillside in the grey light of dawn as the leaves go from black to green with the soft brushstrokes of the light. A bat got into the house through an open door and in the early hours of morning I found it lying exhausted in the kitchen sink and I slowly watched it die when I released it outside.

That image I carry with me.

I can barely remember a single headline in my life.

I can remember the first chicken I decapitated.

I can remember the first fish I ripped the guts out of.

I can remember the warm sticking feeling of the entrails on the deer as it spilled out from the slit I'd made from the rib cage to the asshole.

I just can't remember when.

Like that girl and my hand slid down.

Like that first fist that hit my face.

But almost certainly, it was morning, I am one, maybe two, I'm out on the grass in the farmyard, sound of clucking in the air, cattle lowing from the barn, the scent of my mother in my nostrils from that moment she set me down and I rub the green blades and my little hand mashes them and my fingers go green.

I didn't want to get up, ever.

I suck my fingers and inhale.

This, I should note, becomes a habit.

I'm leavin' here today

Yes, I'm goin' back home to stay

I am told to always aim for the middle and fire every round.

I am told never to point a gun at someone except to kill them.

I am given a shotgun, a rifle and the pistol my uncle used to blow his brains out.

I am told never to believe the way killing is portrayed in the movies.

I am told never to give ground.

And always keep the gun loaded.

Then he sits back, guzzles his quart of beer, and falls silent.

That is my father on the family land ethic.

There is no question period.

I am born between two points:

a stone axe head found in a plowed field and placed on a fence post by my father, and the scars of an ancient and huge glacial lake whose collapse helped feed and sculpt the great delta of the Mississippi River.

I was born to be erased.

And accept this fact.

The ground under my feet has always meant more to me than the people around me.

I have dreamed all of my life about a house down by the river where I will live out my days, let the land heal and grow ever more fruitful.

I have dreamed all of my life of burning this place to the ground and then departing into the dark of night while the flames lick the ground.

I am not about closure. I am about reopening wounds and slashing through the scar tissue to the place where the dreams sleep and wait to come back to life.

I whittle the end of a stick, slide on a marshmallow and roast it black over the small wood fire as lightning bugs glow in the dusk. Images float before me like a dream.

The Case jackknife is razor sharp from constant honing on a whetstone, the air rich with the smell of oil as I stroke the blade.

Shucking fresh corn, the rank odor on my hands as the dogs gather round full of hope and curiosity.

The staleness of a city apartment in winter, the fresh blast of aroma rising from straw, cow shit and the Holsteins entering the barn door in a precise order and then waiting to be hobbled and milked.

I inhale the scent of the weeds as I hack at them in the garden and embrace scent rising off the black earth into my face.

The breath of long-dead dogs floats serenely in my memories and in my heart. The coarse laughter of vanished aunts and uncles warms the coldest night for me. Lately, distant moments of afternoon or morning, long-ago smells and sounds and colors keep brushing against my face.

I am three and I think of old man Zeiger sitting on his porch in Chicago whittling dogs that he then stained. He would speak in halting English and this seemed normal for the time, an America where immigrants and foreign tongues were so common as to be unremarkable. For years, I had a small dog he placed in my childish hands, the body dimpled by the blade to simulate fur.

I keep remembering things of no consequence. The rush I feel as the smell comes off chickens roasting on the grill in the late afternoon, the chatter of women fussing in the kitchen amid the pies and vegetables and salads and bawdy talk, the sour smell wafting off the beers in the paws of the men, the laughter of my father at his own absurdity and in

the distance, the hens clucking as they scratch and feed.

That guinea hen pausing just before it is going to peck out my sister's eye and the crack of the rifle as my mother on the back porch of the farmhouse cuts it down.

I have despised America's view of itself most of my life—the belief that we are a city on a hill shining grace and light onto other nations, that we only fight defensive wars, that we have solved the problem of class by pretending everyone is middle class. And that race is a detail in our long illustrious past.

Thirteen thousand years ago, a large meteor apparently struck North America and demolished many life forms. Paleo-Indian artifacts abruptly ended up in the layers of soil. Most of the mega-fauna suddenly disappeared. Fires raged and turned entire ecosystems to ash.

National identity is a fabrication and comes and goes with the vast migrations of peoples. When Hadrian built his famous wall the people north of the wall were not Scots and the people south of the wall were not English. And reading of the evidence of the human presence in Europe over the last ten thousand years makes me realize the continent has been a constant movement of people.

Hunger has pushed me to go into deep time, that place before my life began and before written language began, to plow the very soil of my world. And to stare into the slivers of life I have known in my family. This last fact surprises me.

There is a big box at my feet, one I have been avoiding for three years. It is the past that my mother flung into my present, things found after she died that she had hoarded during her hard journey. My father's mother and father stare up at me from an old photograph, one that was probably taken in the '20s or '30s. I know my grandfather died in '43, died angry since he was determined to outlast World War II and see his youngest son home from the killing ground. My grandmother died several years before that. I was born after they were both in the ground. She stares out with kindly eyes. She was never disturbed by anything, or spoke a harsh word. He looks like a bomb about to go off, his Stetson planted on his head, a coat, white shirt and stained trousers. They stand in the doorway of some small rural home in Iowa.

These things are easy for me.

But there are these piles of letters, letters going back to World War I, and a neatly tied bundle of my mother's and father's love letters. I have never

read a line of these. They have sat in the box in my storage shed as I crept slowly toward them.

Now I feel ready.

I look in the box and think of Pandora and I am grateful for what she unleashed on the tedium of the world. I reach down, stare at a postmark, notice the old worn quality of the print dress my grandmother wears in the photograph.

I've got no time for talkin' I've got to keep on walkin'

American lives are supposed to have straight narratives ending in redemption. I don't believe lives are straight stories. And I don't believe in redemption. You can only be forgiven if you have not really had a life.

Nor do I think a life can simply be a place. All lives take place somewhere but all places are larger than the lives that scamper across them.

A life can have meaning without having a lesson.

My life is about dirt.

There are other things in the mix. No one can speak honestly of American ground without facing race. Before I am three, I am riding on the backseat of a car into Lemont, Illinois, as the adults state with pride that no black person can be in the town after nightfall. Before I am three, I am looking down from the farm at Romeoville, Illinois, where blacks were murdered and driven out in the 1890s. I am in the bayou below New Orleans in the '50s visiting kin of my aunt. I am sitting on the levee in Rosedale, Mississippi, in the '60s drinking moonshine with a black bootlegger. I see a notice filed by Andrew Jackson promising a reward for the return of his runaway slave. Like the ground itself, all these events are of a piece to me. The separations biographies insist upon—the

life and the work—I deny.

Just as the breaking of the ice dike thousands of years ago in the valley below the farm where I was born happened yesterday for me. And the Kankakee Torrent still roars in my ears as it casts billions of tons of soil downstream to create the delta where I'll drink white lightning with the bootlegger.

Everything is held together by my mind and my mind is simply a tool for understanding my hunger for dirt. The distance between the gumbo of the delta and the hard winter ground of the Dakotas is zero for me.

I move upstream, paddle in

the water. The current is weak, the banks green, brush leans over, beaver watch me pass.

I once bought a canoe, worked the abandoned rivers where rapids kept out boats and no one bothered to dredge and channel. The silence owns, the paddle slips into the water, executes the J stroke, lifts and returns to the front, slices back into the current, and never a sound. Bought a fiberglass model just for the added silence. Deer would come into view standing in the water and drinking and never hear the approach.

I was sure then. Enough days and nights, camping light, bag never warm enough, food no more than grub, black coffee before dawn, then push off, I was sure that the ground would come to hand, my hand.

Around each bend, I thought the place would be there, waiting by the side.

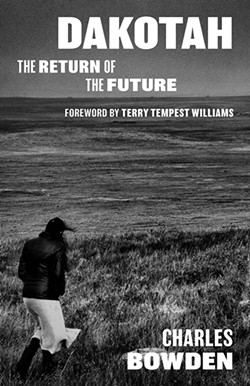

Excerpted from Dakotah: The Return of the Future, by Charles Bowden. Used with permission from the University of Texas Press, © 2019