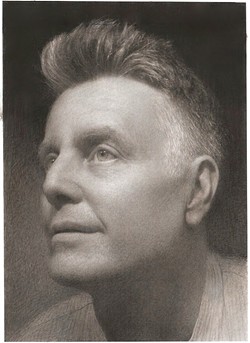

Chris Rush, author of the daring new memoir The Light Years, first got Tucson's attention more 20 years ago, when he painted a comical mural of a baby's fat-cheeked face on a downtown wall. It was adorned with three happy words: Eat. Fly. Cake.

But Rush revealed his serious side in 2000 in one of the most extraordinary art exhibitions Tucson has ever seen. In his solo show The Lost Portraits at the Tucson Museum of Art, Rush unveiled masterly conte crayon drawings of disabled children. Inspired by disabled children he'd worked with at the performance group Third Street Kids, Rush honored his subjects with honest renderings of their bodies. He drew heads that were small and twisted, legs that had no bones, hands that never grew. Most importantly, in every portrait, each child radiated a transcendent light.

These Old Master-style artworks catapulted Rush into artistic success. Etherton Gallery—upstairs from that long-gone baby mural—represents him, and his works are collected by museums.

Now Rush has published a head-spinning narrative of his own precarious adolescence that is already winning superlatives. Vice called The Light Years a "lucid miracle" and a "literary masterpiece." Set in the late '60s and early '70s, the story plays out in New Jersey, Idaho, California, and Tucson, where a broken Rush finally finds some respite.

The memoir is a painful and astonishing chronicle of family dysfunction, drugs, addiction and attempted murder, alongside the coming of age of a young boy reveling in his gayness. Writing more than 40 years after the events in the book, Rush shows some sense of forgiveness for his negligent mother, for his violent father, even for the drug dealers who almost let him die. There's a sense of transcendence in the book, with Rush seeing the light in a dark world, much like the light he found in the disabled children

The excerpt here takes place in Tucson. With his father threatening the son he calls a "goddam queer" and his mother trying to pacify her husband, young Chris has already been shipped off to boarding schools. This time the family sends him to live in Tucson with his drug-dealing sister and her husband.

Miracle of the Dust

An excerpt from Tucson artist Chris Rush’s memoir The Light Years

Lu's stash house sat on a black rock, surrounded by saguaros. Drugs from Mexico waited there to be flipped or shipped. Lu needed someone to live at the house and keep an eye on things, and to make the place seem normal. The last tenant—another of Lu's crew—had fled, worried that the cops had the place under surveillance.

"The guy was paranoid," Lu assured us. "But you know what to do if anything goes down."

We did know what to do: keep our mouths shut—wait for the lawyers. For our silence, there were prayerful promises of bail and legal assistance. "We're family," Lu said.

Staying in the house involved some risk, but Donna and Vinnie couldn't pass up the offer of free rent. And Donna was glad to babysit product, rather than transport it.

With the feel of a beach bungalow or a motel, the place was both worn-out and never really lived in. Lacy grandma curtains, church candles, a funky lamp made from the skeleton of a cactus. Nothing in the place matched, or mattered. But the picture window in the living room was splendid: the whole valley of Tucson, spread out below. In the distance, freight trains chugged by like toys.

It took us three days to drive to Arizona. As Vinnie's old Chevy station wagon pushed on, with no AC, I wondered if my sister missed the sports car she'd given back to my parents in a huff of pride.

But she was free now, we all were—and that meant everything. At night, we slept on blankets in the desert, the sound of the highway like the ocean. The world seemed huge and hollow. I kept hearing my mom's voice. Why are you moving? That's absurd. Your sister is due in two weeks.

I repeated what Donna had told me: It's a business opportunity. During the drive, I had a nightmare—the first since New Jersey.

I woke up screaming, but Donna and Vinnie didn't even stir. I watched the crazy stars and tried to catch my breath.

At sunrise, we were off again. As the heat grew, mirages rose from the blacktop and the mountains floated by as if on some silver sea.

When we crossed the Colorado, Donna poured us warm lemonade. We toasted with paper cups. Driving into Arizona, into the wastelands of the Gila, I thought of my brothers, drinking glasses of ice-cold milk, my father eating saltines with shaky hands.

And Mother with her checkbook and pen, writing my name in lovely loops.

Pay to the order of Christopher Scott Rush.

Twenty-five dollars and no cents. Twenty-five dollars and no sense.

Later, I wrote both versions in my sketchbook. Drew a starry sky full of coins like flying saucers.

A week later, Donna handing me my lunch in a paper bag, saying: Off you go . . .

Strolling down the lava driveway with my avocado and alfalfa sprout sandwich, I stood in the road, a stick figure waiting for a yellow bus. Worried about yet another new school, I felt the old familiar sick. Looking down at my favorite shirt, a gauzy tunic coiled with blue embroidery, I tried to feel better. Donna had bought this shirt for me. It was my shield of flowers. Carefully, I rehearsed my lines: Hi, I'm Chris—from California! (New Jersey would be wiped from my résumé.)

The moment I got on the bus, my peers were transfixed. Their mouths hung open as they searched for the right word to welcome me aboard. Of course, that word was faggot. I took a seat at the front of the bus, alone, and stared out the window. Like in the cartoon where the coyote chases the roadrunner, the desert repeated itself, over and over.

At school, I knew the drill. You're a robot—keep walking.

As I'd feared, the long-haired boys of Tamalpais High had been replaced by crew cuts and cowboy hats. Many fellows sported handsome blue jackets with yellow letters: Future Farmers of America.

Attending school assembly in the auditorium, I was unsure where to sit. A young cowhand approached. He looked me over and smiled— his teeth Halloween black. He said, "Hey, baby, want a kiss?" and then hocked chew on my shirt.

When I came home from school, the house smelled of reefer and refried beans. I hid my stained shirt behind my books.

Donna said, "So—how was it?" I said, "My teachers are nice."

I didn't want her to worry. She was nine months pregnant, in a borrowed house, with no money and a nude husband.

Most days, after school, I hiked in the hills behind the house. I explored extinct volcanoes and cliffs rotten with caves. Found geodes and blue agate, pulled quartz crystals from the ground like broken teeth. Viewed from the peaks, our little house looked like a boat stranded on a rock, waiting for a wave.

But the wave never came.

The desert was a difficult place to live. By midday, boundless light overwhelmed the valley. Barely a shadow could survive. We all looked forward to sunset—its golden rays and purple shade. After hard days, the sunsets were soft and sweet.

On Saturday mornings, we picked up our mail at a tiny rural post office. Only then did we see our neighbors, the ranchers who lived down long dirt driveways. These men sometimes nodded, but never smiled. I studied their slow saunter, their bright eyes, their faces wrecked by sun. As we collected our letters, their wives glared at us. Maybe we seemed too happy. Maybe it was our hair.

One day, there was a package from Lu at the P.O. Box—some hash, I think. The old woman behind the counter spoke kindly to pregnant Donna. "Oh, I bet it's baby clothes. What do you want, dear—a boy or a girl?"

My sister smiled. "My husband and I like both sexes."

The woman was perplexed, staring at the feathers in Vinnie's hair and my yellow pajama top. As she handed Donna the cardboard box, she frowned—her old-lady lips snapped shut.

We lived in pretend-Arizona. Vinnie and Donna thought they were pioneers, reading the Bible by candlelight, baking bread, birthing baby at home. But it was a fantasy, an attempt to live in a place as strange as the moon.

The baby, though, was no fantasy. Miles from medical care, we waited. The Chevy was a wreck. We had no phone. I knew that Vinnie and Donna had consulted with their chiropractor, who vigorously encouraged home birth. Dr. Kelly assured them that there was nothing to worry about. Also, Vinnie had spoken to Jesus about our situation—and Jesus told Vinnie to deliver the baby himself. And that I would assist.

No way. I suggested Donna go to a hospital.

"No hospital," Vinnie said. "My child will not be traumatized by doctors."

But what about my trauma?

Vinnie and Donna didn't say much about the birth itself, but from the how-to books lying around, I'd determined that someday soon, my sister would be screaming in agony while her guts exploded.

I hoped I'd be at school. Many of the kids at Red Rock High were Mexican and spoke no English. I sat with them in the backs of classrooms. I did my work and, like them, said nothing at all.

One lunch, I saw a tiny boy sitting under a tree. He had on a blue Alice in Wonderland T-shirt. From under a mop of red hair, he smiled at me.

Too shy to go over, I walked to my next class.

Around this time, I got a homemade postcard from my friend Sean—whose sister, Darla, had given me the tarot reading. Sean, remembering the reading, had drawn the Fool on the front. On the back was written:

Chris, have you fallen off a cliff? Or are you in love?

I woke up to the sound of a car in our driveway. I was scared, since no one ever came to the house. When I looked out my window I saw a pretty woman with a funny little kid—and then I realized it was Lu and Jingle.

I got dressed and ran into the kitchen, where Jingle was unpacking groceries. She kissed me on the head. Lu shook my hand and said, "Come with me."

Vinnie was already outside with a flashlight and shovels.

Lu led us into the desert. By the beam of the torch, he looked like a fiend in a monster movie, limping past cactus claws and jagged rock.

Pointing with his crutch, Lu said, "See that stone? Dig next to it."

Fearful of scorpions and snakes, Vinnie and I cautiously picked at the dirt, but soon our shovels hit metal. We pulled a big rusted box from the ground—quite heavy.

On the porch, Jingle waited with a tiny silver key. She slid it into the lock and pried open the creaky lid. Inside was a stack of mason jars, each containing a perfect specimen of a different drug. Flowers and powders and tar.

Lu grabbed a jar of buds and then, for only an instant, I saw the money. Beneath the jars of dope sat a big block of cash. It frightened me. Finally it hit me that Lu and Jingle were criminals. And I saw the precariousness of our situation.

Lu snapped the trunk shut, shooed us inside. Jingle locked the box and put the key in her apron. Then on wicker old-lady furniture, we smoked rare herb, and soon I was asleep again.

By morning, the box had disappeared from sight.

Vinnie whispered to me, "That was serious cash, man. There's gonna be a major deal."

I skipped school to see what would happen next.

Strange people dropped by the house. Unlike Lu's associates in Marin, these people were not hipsters. Up the dusty drive, men arrived in pickups—rugged men with short hair and sunglasses, cowboy hats and scuffed boots. They all carried paper sacks.

Each sack contained a kilo brick. The bricks represented different loads of pot that had recently crossed the border, from Mexico. Lu was shopping for product.

From the living room, I watched Jingle greet each guest with a cold beer. There were no introductions—and after a moment of small talk, Lu would open the bag. He'd sniff at the brick and peel off enough for a joint. Vinnie helped him smoke it, but his opinion was never sought.

Donna stayed in her bedroom.

Lu would always walk the dealer outside to the driveway to discuss money. For days, cowboys came and went. Sample kilos piled up under the table like trash.

By then, my sister was past her due date. She was gigantic. I could tell she liked having Jingle around. At night, when the commotion died down, Jingle would sing a hymn just for Donna.

I'd listen from the doorway.

On the table next to my sister's bed, I saw the scissors and syringes, the gauze and bandages. These things worried me. I still wanted Donna to go to a hospital, especially with all these strange men coming and going.

At least Jingle kept singing.

The next night, very late, there were strange voices in the house. I opened my door and saw Lu and Vinnie standing with two mustached men—one with a holster and gun. I must have gasped.

Lu turned and scolded me. "Get back in your room. This doesn't concern you."

I locked my door and listened.

I heard arguing. But I kept telling myself, Vinnie and Donna are protected by God. Nothing bad could happen.

And though I understood that Lu and Jingle were criminals—I also knew they were Christians, and that they loved me. I did the only thing that made sense. I said my prayers. Our Father Who art in heaven . . .

I prayed until I fell asleep.

I awoke to a scream.

Donna!

I jumped out of bed and ran from my room—stumbling over bricks of pot wrapped in pink plastic. There was a pyramid of product in the living room, stacked over my head. Squeezing past, I called out to my sister.

Everyone turned. Donna was lying on her bed, naked. Lu and Jingle and Vinnie, plus some people I didn't know, stood around her.

Donna's eyes met mine. "Baby's coming."

Vinnie put his arm around my shoulder and walked me back into the living room.

"There were men with guns," I said. "Last night."

"You were dreaming. Everything's fine."

"Where's our furniture?"

"On the porch—just until the buyers take the product." He whispered, "Lu promised me and Donna a nice cut."

"Who are those people?" I said, gesturing toward his and Donna's room.

"The buyers. Nice people. Donna asked them to stay for the birth, for good luck. Praise God."

Another scream from the bedroom.

Lu came out, sweating. He put some tabs of white acid in my hand.

"Take your sacrament. There's going to be a miracle." I took five tabs, then ate a bowl of Grape-Nuts.

Twenty feet away, my sister sounded like an animal in pain.

Vinnie and Donna's bedroom had three walls of windows, with incredible views, but that morning there were only two things anyone saw: my sister's eyes, which were beautiful, and her vagina, which was mutating at a rapid pace.

The dealers, who'd come by to score pot, found themselves hypnotized by my sister's privates. I think they were relieved to look away and introduce themselves. "I'm Sherry. You're the brother? What an experience for you!"

Sherry was a short Jewish lesbian, plaid shirt to her knees. She was clearly the boss, keeping an eye on a bag in the corner of the room, which I assumed was full of cash. Buffalo, her employee, shook my hand a little too hard. He was a burly, red-bearded guy, with a belt buckle big as a dinner plate.

"Hey," he said. "I met you when you were, like, 10. You had on a pink cape."

A memory flashed from a distant planet. "Meet Heidi-girl!" Buffalo said.

Heidi was blonde and pretty and pale, with fluttering white lashes.

She looked a bit distressed.

No star had guided these three to the manger—it was the weed. Heidi went to the kitchen and cut up a pineapple. Jingle made iced tea. I stood around with a flyswatter. Then came a much more intense scream. Everyone gathered around Donna. Vinnie was at her side, coaching her breathing—telling her not to be afraid. His stopwatch categorized each wave of pain. Small talk faded away.

A mountain of pot was suddenly the most boring thing in the world.

When the crown of the baby's head appeared between my sister's legs, I could not imagine how the creature would make it out. Donna was in a trance, breathing hard, eyes available only to her husband.

When she cried, Vinnie was steady, following her agony, reminding her that the baby was almost there. Jingle wiped the sweat from my sister's brow. Heidi, terrified, held my sister's hand. Lu, Buffalo, and I stood at the foot of the bed with Sherry—all of us silent, awestruck.

Vinnie turned to me. "Get your sister a glass of water."

As I handed my sister the cup, the water glittered like diamonds. My sister drank and sighed and closed her eyes, pausing as the room slowly detached from the earth. The valley disappeared, far below.

The sun follows us as we float away, bright white sheets and blood, blood, blood. I've never been more scared. My sister has changed shape again. She is wide open. The room is dizzy and dangerous.

The head emerges: ancient face, closed eyes, passive, patient, as if it had been waiting for centuries. I hear my sister's wailing, pleading to God to help her. God, God, God. I feel my fear rise up again. But Vinnie is tender. He touches the new one's face, the child stuck between worlds.

The contractions are terrible to watch. My sister pushes and screams, pushes and screams. The baby's position is impossible. Rapt in terror, I watch the baby's head, a red rock, an orb surrounded by sheets of blood. I do not understand. How can this dark moon be a person?

"Oh—Oh—Ohhhhh," my sister screams, and out flies the baby.

Vinnie catches the slippery thing and brings it to the sunlight. The child, mysterious as stone, is covered with thick slime, maroon and yellow. But the stone breathes—it cries and punches the new air.

Instantly, it becomes a girl.

My sister weeps with joy. We all weep. The drug dealers hug. Donna holds her daughter, the umbilical cord still attached. The throbbing coil is inconceivably monstrous, a bloody purple snake.

I drop the flyswatter and go to my sister. As I look into her eyes, she smiles at me—tears and laughter. Up close, the child is covered with fine hair like a wolf-baby, a wolf with the face of an old woman.

Vinnie readies to cut the cord. I cannot look.

The child, untethered, joins the human race. Vinnie calls her

Jelissa.

She takes my sister's breast.

I cannot remember my mother's breast.

I don't recall ever feeling the acid Lu gave me. I remember only the trip of a baby coming into this world. I remember the delirious fear that struck me soon after seeing the umbilical cord cut. Who will protect this tiny thing?

It takes me a few seconds to remember: It has parents—it has afamily.

Later in the afternoon, Vinnie and I drive to a pay phone to call our folks. He spoke to his first, smiling and crying. My call was more complicated. Donna had lied to Mom, claiming she was having the baby in a hospital. Mom was thrilled by the news and asked me the name of the hospital so she could send Donna flowers.

"Actually," I said, "we had the baby at home. I helped Vinnie deliver her."

"Are you insane?" my mother shouted—so loudly that Vinnie could hear.

We both started laughing.

And then Mom was laughing, too. I told her I loved her.

At the house, Donna and the baby were asleep. Jingle cooked dinner while the menfolk got high. The buyers had gone to get a truck.

I recall someone helping me to bed.

In the morning, the load was gone. I helped Jingle sweep up the shake from the floor—stems and pot dust. When I saw her about to toss it out the back door, I said to her, "Don't throw it away! I can share it with my friends."

I was thinking of the shaggy-haired boy in the Alice in Wonderland T-shirt.

Jingle shook her head and put the shake in a paper grocery sack, and then sealed it shut like an oversized lunch bag. "God bless you and your dirty little friends."

Vinnie and I moved the furniture back into the living room. The house smelled like hay, diapers, beans.

Before nightfall, Lu and Jingle were ready to leave. Lu gave me a bottle of LSD, which he shook like a baby rattle. Jingle laid her hand silently on my head. I could feel the blessing she was giving me.

Outside, she sang a final hymn:

When I thirst, He bids me go,

To where the quiet waters flow . . .

Excerpted from The Light Years: A Memoir by Chris Rush. Published Farrar, Straus and Giroux, April 2. Copyright © 2019 by Chris Rush. All rights reserved.