The actor is telling a story about how appearing on Columbo with Peter Falk was one of his three life goals. The 90-minute episode sees the actor playing a hospital patient when Columbo checks in, undercover. Pulpy TV thrills ensue.

The actor digs through a box and pulls from it a dusty framed photo. It shows him wearing a bathrobe, standing beside a suited Peter Falk, both are on set, grinning. The yellowing image reveals more: The actors were born more than 20 years apart, generations removed from Hollywood now, but similarities are there, odd circumstances and all. Falk had lost an eye to cancer as a kid and the actor, Alexander Folk, was born black in the back of a grocery store in South Central Los Angeles. Inauspicious starts for actorly careers, to be sure. Falk, at least, had the white skin advantage, allowed to embrace various identities as an actor.

There's the final scene of National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation, too, memorable not only because the comedy is firmly ensconced in the canon of classic American movies—our culture guaranteed this—but also because Folk, as the dapper SWAT commander, is so recognizable. In the finale, Folk's character takes charge of the Griswald family home, informing Frank Shirly (Brian Doyle-Murray) he'd beat him with rubber hose if he could. Folk is comical as the good guy black man—a still-rare role by late-'80s Hollywood. That humor and the actor's considerable onscreen presence notwithstanding, it's hard to imagine a black cop beating down a white dude.

Folk's right eye still shows damage from that time back in '67 when cops wrenched him from his car, Rodney King-style, and beat him nearly to death. They tossed him into a jail cell, too, threatening even more damage to his body should he file a police report. Folk is a black man after all. Guilty as charged.

That year Norman Jewson's In the Heat of the Night, starring Sidney Poitier, gets released. It essays a smart black detective working with an ignorant white cop. The civil-rights barnburner helps soothe long-simmering tensions in a town half built on racist celluloid. It's easy to think of the racist Hollywood, from silent Birth of a Nation, to Song of the South and Gone with the Wind, or Soul Man, or just pick one.

Folk's words lift on all kinds of unjaded sparkle and his stories sometimes burst with raucous impressions accented with rubbery facial expressions. He's that amiable black character actor, alert with authority, and mirth. Ceaseless grins and relentless optimism. It's easy to slip into his personal nostalgias because when he talks of them, it invites, like a world without end.

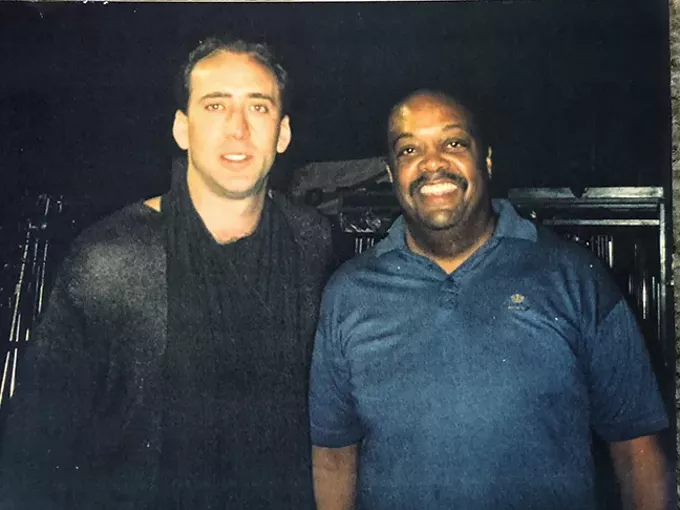

Like how he adamantly claims he's only been drunk once in his life yet he occupied stools and purchased countless drinks for so many others in now-gone, actor-populating Hollywood watering holes. He'll reminisce on running buds, like film director/stunt man Hal Needham, who helmed Smokey and the Bandit, among others. He says, "Nic Cage was cool, man, not bizarre at all," and leaves it at that. (Folk was the store clerk robbed in Cage's City of Angels). But no broom necessary to sweep dropped names. He doesn't offer much when pressed for film-set dirt; instead, what becomes clear is his gratitude to have been hired for work at all. Work that lasted decades, a long arc on Murder She Wrote, the crackhouse cop on Naked Gun ½, the prison guard in Sid and Nancy and on and on and on—his film and TV credits run as long as a month of Sundays, reveal a steady-as-she-goes career, purely working-class Hollywood, if there is such a thing.

Forget classic Tinseltown shenanigans, too: His one brush with cocaine found it OK for kicks. The coke man apparently had a heart of gold and sensed the inner-train wreck Folk might become and cut him off after one line. That was it. Folk's grateful for that guy too, even if it did keep him out of correct Hollywood parties and off the correct star-making teat. Dude didn't party. Maybe it had something to do with his Southern Methodist-Episcopal upbringing. Besides, his brothers suffered the booze, but lived. He witnessed the damage.

In fact, Folk looks pretty damn good for a 72-year-old. There are no bad face peels or visible afterburns of a Hollywood career, no evidence of booze bloat and rehab stints gone janky.

"I have a procedure that I've been using," he says, no irony.

His nails and teeth are perfect.

Today Folk's comfy in black trousers, slip-on moccasins. He's wearing a white oxford shirt that sports a Jelly of the Month Club logo—yes, from Christmas Vacation— and it somehow clashes with his gray Van Dyke. His exploratory brown eyes are the only feature that make him seem actorly.

His one-bedroom Tucson apartment features a view of sun-dappled tennis courts, the mesquite-rich Pantano Wash, and swollen homes of the Tucson Country Club behind it. A short walk to Costco. The living room boasts a director's chair with his name on it, a flatscreen TV and a few framed movie posters including Tombstone and his Dream Girls. His belongings could roll up into a good-sized rug and be tossed in a van. How he likes it. Spartan, hassle free. "You never know, I could be out of here soon and living in Turkey or somewhere."

A wall map dominates Folk's little dining area, where we sit around a two-chair breakfast table. Colored pins on the map represent places he's visited, including 40 or so countries. He'll talk the beauty of Tasmania ("And I don't know anyone who's been to Tasmania"), the insanity of the Bangkok sex industry ("No one should ever do anything there," and leaves it at that), and the spectacle of Australia, before his acting career. "I'm a junky for travel," he says. "Can't even look at the Sunday Times, I'll book a trip walking to the bathroom."

Sixty-five years in L.A. was enough. His "honorable withdrawal" at classic retirement age from the Screen Actors Guild was more a sabbatical. He's not done. But it's the acting that paid for his life, and the extensive travel. That's something. And if you grew up consuming pop culture in the '80s and '90s you'd go, "oh, yeah, that guy."

The juicier parts of that acting sometimes took years ("I got the smaller roles, only ones they'd let me do"). He read for a part in 2006's Dream Girls and waited months. He figured he'd lost the part. One day his agent called, said he begins shooting in two weeks. "Everyone in Hollywood wanted in that movie," Folk says. He played dad to Jennifer Hudson's character, for which she won an Oscar. Meantime, his grin, voice and carriage starred in countless TV commercials, many of which are found on YouTube.

He moved to Tucson to be close to his daughter, who now lives in Sierra Vista. She's more of a surrogate daughter. Two decades ago he became a kind of father figure, helping out four Asian children. "I walked into their mother's convenience store in West Hollywood," he says. "I saw some stuff that may have been lacking. So I've been available to them."

(A 1972 marriage lasted nine years and change and produced one son, who Folk says is lost. When pressed, Folk explains his son brought drugs into his home when he shouldn't have. Folk finally tossed his adult son out for good.)

Born in a grocery store in South Los Angeles, on Memorial Day, 1946, Folk is the youngest of four brothers (all still living). No birth certificate made for hassles later in life.

He has mixed remembrances of childhood, and at one point calls it "Leave it to Beaver." Either his parents, Alabama-raised Southern Methodists, were gifted at insulating the family from externals, sequestered in the black enclave in South Central L.A. where Alexander grew up, or his words are PR spin, or he was one in a million.

Mom cleaned house for "rich white folks" in Beverly Hills etc. "It's all the work they could find." Dad worked in a factory "for 37 years and six months at a job he hated, Western Insulated Wire Company" putting rubber on wires for lamp cords and such. "He had to do it." When he retired they gave him a gold watch.

Folk discovered a desire to act at 12. Dad forced him to do his first play, at the family church, the oldest African-American church in Los Angeles, the African Methodist Episcopal. (Folk laments the church tear-down, and relocation. "That much black history, more than 100 years of black history when they tore that original church down. They put up a box store in its place. Bothers me to this day.")

At the end of that play, Folk says, he got a standing ovation. "Nothing felt that good."

Almost nothing. It took a couple years, but Folk learned his route to women was through acting.

"As good as acting felt, girls felt better." He flings his arms into the air, his voice rises 30 db. "I couldn't spell the word 'girls.' I didn't know what girls were for except for spitballs. I was so stupid."

He was in gangs too back then, but with an asterisk. Gangs were more West Side Story than bloods and crips, featuring fetching monikers like The Gladiators and The Businessmen. They'd clash at football games. "In those days the gangs were different," Folk says. "We weren't killing each other; there were no crips and bloods. My brothers did some things, running with the wrong crowd. But I didn't want to do business in the streets."

Folk graduated high school in '64. Four years later he's living in Hollywood, spitting distance from Paramount Studios, getting work as an extra, studying acting and film at L.A. City College, working day jobs too. Whatever it took. Dude was going to act, despite his white counterparts getting all the work. And the work came. Always.

Folk is pretty psyched Christmas Vacation is in the cinematic pantheon. And how it's aired 24 hours non-stop on at least one U.S. TV station at Christmastime. Residuals come in handy; a recent Christmas Vacation residual totaled $1,200. Sometimes it's pennies from work he did 40 years ago.

He's pitching to producers a script he wrote, too, a detective story set in the '40s and '50s called Central Avenue. Takes place around the old Dunbar Hotel, and in the black neighborhoods where Folk grew up, when he'd sell the Los Angeles Times on the corner of Manchester and Central. The story is built around undocumented parts of L.A. history, and it's not an easy sell. "When it comes to a black story, no one wants to know," he says.

Folk is recognizable, not famous, and decades of getting recognized has given his character magnetism, an X-factor to draw in strangers. That and how he made peace in an industry that most always favored white faces. The endless rejections.

He knows. "I'm not Denzel Washington," he says, "but sometimes women will come on to me. I still get recognized, mostly from Christmas Vacation and Dream Girls. I will not lie."

The opportunity has seized and penned a pair of slim personal-growth volumes he takes seriously. For starters he's a lover of women and god. Born of Southern Methodist. Women — God's Second Greatest Gift to Humanity. I ask him if women are the second greatest gift to humanity, what could be the first greatest gift?

"Jesus is," he laughs. As if.

The other is entitled Go Home — A Guide to Achieving Your Goals While Dealing with Life's Inconveniences. It's about looking within, a set of beliefs to answer his life questions, from personal experience, which he tells in plainspoken tones, weaving in first-person anecdotes from Los Angeles.

The books read of simple truths, active platitudes, honest words, and a benevolence borne of 72 years on the planet.

"Look, I haven't had a 9-5 job since 1979," he says. "I have never known where my next check was coming from. But it always came. So how long does luck and coincidence last?"

His books can be easily found on Amazon.

"They're so simple even infants can understand it."

Folk's two other acting goals never came to be. One was The Godfather, but that was too lofty a target. Besides, the only black character in the first Godfather was a stable boy who briefly handled the prized horse, which was decapitated. The other was to appear in any James Bond flick. Hardly a chance. No winning actor ever said Hollywood was easy. Especially a black one. Not now, not in the '80s, not ever.

Folk's pop died in December last year, at 99. Back in 2010, Folk took him on a road trip, and they were in Flagstaff. Folk went into a full-blown stroke. He describes it like a merry-go-round that just started picking up speed until the earth seemed to spin off its axis. He suffered two strokes that year and wound up in a wheelchair.

"There can never be bad without the good," he says. His eyes well up and this isn't acting, or maybe it is and he's that good. "I was in a wheelchair and now I walk again."

He talks of death, referencing a theme in his books: "If you have a problem that you can fix, what's the problem? Like death. I don't call that a problem. I'm extremely ready for death. Can you do anything about it? No. Unmake friends with it? Hey, death, want some lunch?" He pauses. "But I did ask God to take me gently when I go."