Monday, October 4, 2021

Audit’ expert Shiva Ayyadurai didn’t understand election procedures, made a number of false signature claims

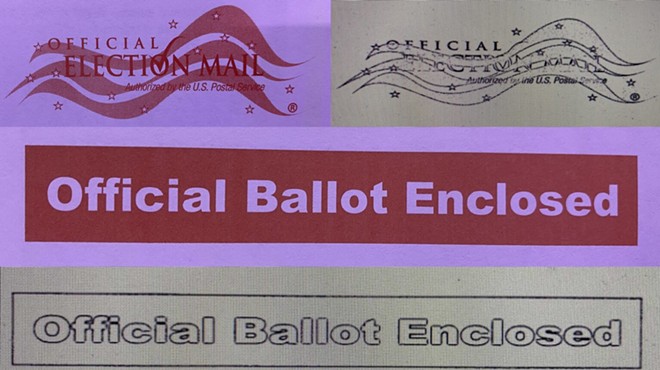

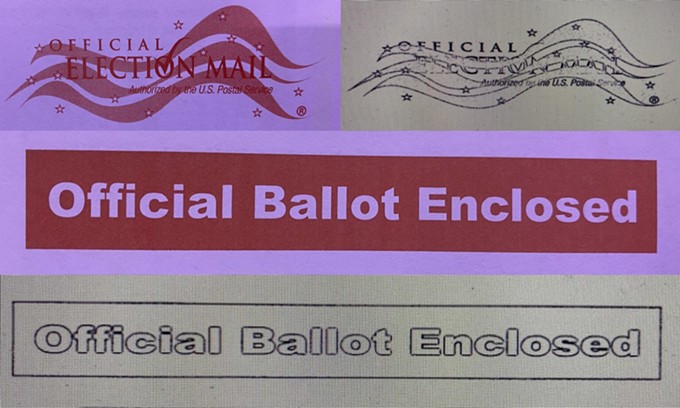

The audience in the Senate gallery oohed and aahed as Shiva Ayyadurai drew its attention to a “verified and approved” stamp that appeared behind a triangle on the image of an early ballot envelope, unsubtly suggesting that it might have been pre-printed that way.

“It’s almost as though it was imaged on there. I don’t want to say Photoshopped, but put on there. But it’s quite fascinating. I’m sure there’s some explanation for this,” Ayyadurai said. The remark elicited laughter from an audience largely composed of audit supporters who believed, without factual basis, that the 2020 election was rigged against Donald Trump, a position Ayyadurai himself has aggressively promoted.

It turns out there was an explanation, and a simple one at that. But Ayyadurai appeared to have absolutely no knowledge of Maricopa County policies and procedures regarding the early ballot envelopes and signature verification. That shortcoming would be a consistent theme as he presented his findings as part of the so-called audit of the election in Maricopa County, portraying commonplace occurrences and standard procedures as potentially suspicious.

And Senate President Karen Fann has asked the attorney general to investigate Ayyadurai’s obviously false findings.

Ayyadurai, known to his fans online simply as Dr. Shiva, is an MIT-trained engineer and entrepreneur known for his disputed claim that he invented email. He has a history of promoting discredited and debunked conspiracy theories about the 2020 election, including during a day-long event at the downtown Phoenix Hyatt several weeks after the election that featured Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani.

The claim about the triangle on the early ballot envelopes was perhaps the most attention-grabbing of the numerous findings he presented during a presentation on Sept. 24, as the team that led Senate President Karen Fann’s review of the 2020 election results in Maricopa County.

“I would consider this potentially a critical anomaly,” Ayyadurai said.

But to those who understand how elections work, the “critical anomaly” was anything but. In fact, it’s not only not an anomaly at all, it’s exactly how the systems used to safeguard the election are designed to work.

‘Hollowed out’ shapes increase speed and decrease file size

When Runbeck Election Services, the company that prints Maricopa County’s ballots and envelopes, scans the outbound and incoming early ballot envelopes, it does so in a binary format that only uses black and white pixels, with no gray shading. To save space with its file sizes and increase the speed at which ballots and envelopes can be scanned, the binary format doesn’t fill in blocks of solid color, said Jeff Ellington, Runbeck’s CEO.

So, the solid black triangles that point to the signature box on the envelopes become white triangles with black borders. All of the ink inside the triangles and other shapes, including any parts of the approval stamps that happened to be made over the triangle, are removed. The Arizona Mirror was shown examples of this technology from the scanning process of Arizona and Colorado ballot envelopes at Runbeck’s Phoenix facility.

Ayyadurai never mentioned in his presentation or in his written report that the triangles on the paper envelopes, unlike in the digital images he analyzed, are solid black. Two smaller, solid red triangles on the ballot return envelopes also appeared hollowed out in the same fashion on the digital images that Ayyadurai displayed.

Ellington said Ayyadurai never contacted his company during his envelope analysis. Wake Technology Services, a company that worked on the audit until it parted ways with the rest of the team in May, contacted Runbeck with some questions early in the process, Ellington said. He asked them to route their questions through the county.

It’s unclear if Wake ever contacted the county, but county officials have repeatedly refused to cooperate in any way with the audit team, which they view as as unacceptably biased — the team is led by adherents of the “stop the steal” movement that promotes false claims of election rigging — and professionally unqualified. It’s also unclear if Ayyadurai made any attempt to contact anyone else who had knowledge of Maricopa County’s election procedures.

Surge in ‘verified and approved’ stamps is a proof of success, not fraud

The triangle issue was far from the only of Ayyadurai’s claims that demonstrated a lack of knowledge about how Maricopa County election officials handle early ballot envelopes and signature verification.

Ayyadurai said that only about 10% of the approximately 1.9 million early ballot envelope images had the “verified and approved” stamps on them, and said the bulk of them appeared to have been approved after the election, with a 25% increase between Nov. 4-9, the six days after the election. The implication was clear that he considered this suspicious.

Had Ayyadurai bothered to ask anyone who had knowledge of or experience with elections work in Maricopa County, he would have learned that there is a simple answer to his question.

Election workers who have been trained in signature verification examine digital images of early ballot envelopes to determine whether voters’ signatures are valid before their ballots are counted. If the signature matches what the Elections Department has on file for that voter, the envelope is opened and the ballot counted. But if the signature doesn’t appear to match, or if there’s no signature at all, the voter’s envelope is pulled out for additional review.

By law, elections officials must give voters an opportunity to rectify or “cure” their signatures. For a missing or potentially bad signature, election officials contact the voters to confirm that they were the ones who signed the envelope. Voters who forget to sign can come in to the Elections Department to sign there.

The reason why so many of the approval stamps came after Nov. 3 is that the Maricopa County Elections Department put additional resources into signature curing in the days after the election, said Megan Gilbertson, a spokeswoman for the Elections Department. By law, voters have five business days after an election to cure defective signatures — and after Election Day, workers who had been verifying signatures largely shift to signature curing duties. Voters cannot cure missing signatures after Election Day.

Tammy Patrick, the senior advisor for elections at Democracy Fund and the former head of federal compliance at the Maricopa County Elections Department, said the largest number of mail-in ballots also come in shortly before Election Day. That became more pronounced last year because of an increase in the use of drop boxes for early ballots, she said.

And the reason most early ballot envelopes don’t have approval stamps is because election workers don’t stamp envelopes if the signatures are verified without the need for additional follow-up. Only envelopes that are approved after missing or potentially invalid signatures are cured receive the stamp. If there’s no need for additional review, election workers never actually handle the physical envelopes during the signature verification process, Gilbertson said — they only review the digital images of the signature area of those envelopes.

Ignorance of elections breeds faulty assumptions and implications

Ayyadurai’s ignorance of Maricopa County’s procedures extended to the process election workers use to actually verify the signatures. He repeatedly commented on the number of signatures that he described as “scribbles,” which he defined as having 1% or less pixel density in the signature box, while anything over 1% was considered a signature. He identified 2,580 such scribbles, which he described as potentially bad or were assumed to be invalid.

Ayyadurai did not have the file of voter signatures and did not conduct any comparisons to determine whether the signatures matched.

Patrick took issue with Ayyadurai’s analysis of the so-called scribbles.

“The very use of that word implies impropriety. It also demonstrates his lack of understanding of signature verification. And now we know why he wasn’t hired to do signature verification,” Patrick said.

Signature verification has nothing to do with legibility. The issue is whether the signatures match the ones on file for that voter, a process that’s conducted by trained professionals, with multiple layers of oversight when questions arise.

Former Maricopa County Recorder Helen Purcell, who held the position for 28 years, said she and her election director once had to call an Arizona Supreme Court justice to confirm that the illegibly scribbled signature on his ballot envelope was correct. She said Ayyadurai’s testimony on numerous points showed a lack of understanding about the processes he was analyzing.

“I just thought his testimony — if you can call it testimony — was a little bit ridiculous,” Purcell said.

The bulk of Ayyadurai’s presentation was devoted to the issue of duplicate ballot envelopes. But he displayed a fundamental misunderstanding of what a duplicate ballot image actually meant, declaring to Fann and Senate Judiciary Chairman Warren Petersen, “Each of these voters submitted two ballots.”

That is blatantly false.

Election officials don’t use the term “duplicate” to refer to ballot images. In election administration, the term “duplication” is used to describe a very specific process of re-copying ballots that can’t be read by tabulation machines for various reasons.

What Ayyadurai referred to as duplicate images appeared to refer to multiple ballot envelope images for the same voter. That generally occurs when two images are made of the same ballot envelope, which most often happens when there is a question or issue with a particular envelope.

When election workers verify signatures on ballot envelopes, they look solely at digital images of the box on the envelope where voters are instructed to affix their signatures. If they can’t verify the signature, or if there is no signature, they physically examine the paper envelope for further verification. If election workers are unable to verify a signature but are able to cure it by contacting a voter, that same envelope is re-scanned after being stamped for approval. If there’s no signature, voters can come into the Elections Department to sign it in person.

Nonetheless, Ayyadurai presented the existence of duplicate envelope images — he questioned why the county didn’t report them in its official canvass — as potentially suspicious.

Ayyadurai drew attention to 1,455 envelopes that he said were stamped as “approved” despite there being no signature in the signature box. Gilbertson said those are most likely instances when a voter affixed a signature elsewhere on the envelope, ignoring the instructions on where to sign. In such cases, election workers would cure the signature, re-scan it and then approve it. Ayyadurai even showed one side-by-side comparison of two envelope images in which part of a signature appeared jutting out from a black redaction box on the line for the phone number.

“If we stamped it as verified, there’s absolutely another signature somewhere else,” Gilbertson said.

Ayyadurai acknowledged during his presentation and in his report that he only looked at the designated signature field and did not look elsewhere on the envelope for signatures.

Auuadurai’s distortions are ‘disingenuous and irresponsible’

Gilbertson said there are other reasons why a ballot might be approved without a proper signature in the box.

There are bipartisan special election boards that personally bring ballots to voters who are in hospitals, nursing homes and assisted living facilities, or who live at home but need assistance voting for various reasons. Technically, those voters are casting early ballots, which are placed into early ballot envelopes with their signatures. Some of those voters have physical difficulties signing, and some even sign with an X.

But because the boards must check their identification, as would happen with an in-person Election Day voter, those ballots bypass the signature verification process entirely and wouldn’t even have an approval stamp, Gilbertson explained.

Ayyadurai showed several side-by-side examples of duplicates that he intimated were problematic. One showed a blank signature box next to a signed signature box — but he didn’t note that it was the signed envelope, not the blank one, with the approval stamp on it.

Patrick said she was exasperated while watching Ayyadurai’s presentation because he kept showing two images of what was clearly the exact same envelope. But multiple images doesn’t mean multiple ballots or multiple votes, she said.

“To take something so simple and distort it and present it as though it was some sort of evidence of malfeasance, fraud or criminal activity is not only disingenuous and irresponsible, but I think it also, in itself, should have some sort of serious repercussion,” she said.

At the end of his presentation, Ayyadurai presented a list of questions for Maricopa County officials that he didn’t know the answer to, including whether the county “received” any duplicate early ballot envelopes, why he found more envelopes with no signatures or bad signatures than the county reported in its official canvass, why most envelopes didn’t have “verified and approved” stamps, why there was an increase in those stamps after the election, why some envelopes with blank signatures fields were approved, and why the stamps appeared behind the triangles on some envelopes.

He even asked what the standard operating procedure was for processing early ballots and for verifying questionable signatures.

Ayyadurai was far from alone. Audit team leader Doug Logan and team member Doug Cotton made numerous claims throughout the more than three-hour presentation in which they portrayed normal, commonplace practices as possibly suspicious while acknowledging that there may be reasonable explanations that they were overlooking.

Ayyadurai, Logan and a spokesman for Logan did not respond to questions from the Mirror and would not say why he didn’t make any effort to learn whether his alleged findings were actually suspicious or whether there were reasonable explanations.

Fann signed a $50,000 contract with Ayyadurai’s company, EchoMail, for his ballot envelope analysis, according to documents obtained by the liberal watchdog group American Oversight. Those records include a separate contract between EchoMail and Cyber Ninjas, Logan’s company.

After listening to Ayyadurai’s presentation for an hour on Friday, Fann and Petersen didn’t ask him a single question about whether he’d taken any steps to verify his claims. Fann also did not respond to questions from the Mirror.

Arizona Mirror is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Arizona Mirror maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jim Small for questions: info@azmirror.com. Follow Arizona Mirror on Facebook and Twitter.