There is something rotten in Diebold, the company that brought us the 2004 drama, "Much Ado About Ohio," with its timeless theme of long lines and too few voting machines at polling places located in Democratic precincts. Next month's midterm elections hold the promise of encore presentations replete with dramatic, breath-holding recounts and disgruntled losers licking their wounds who are too polite (or intimidated) to yell, "FRAUD!" Well, except maybe Howard Dean.

Two years after the 2000 international best-seller, "The Taming of the Florida Chad," President Bush, in a selfless effort to ensure the integrity of the democratic voting process, signed the Help America Vote Act.

HAVA required states and counties to bring their messy voting systems up to date by mandating electronic voting equipment. By sheer coincidence, HAVA's passage delivered huge sums of federal (read: tax) dollars to what an article in Rolling Stone magazine describes as a "tightknit cabal of largely Republican vendors."

It just so happens HAVA's principal backer was a character named Bob Ney, a congressman with close ties to Jack Abramoff, the lobbyist who never let the law stand in the way of increasing his bank balance. Abramoff's firm earned more than a quarter million dollars lobbying for Diebold, reports Rolling Stone.

There's more to the Byzantine plot, and you can read all the diabolical twists in the Oct. 5 issue of Rolling Stone, where you'll learn, among other eye-openers, "The provision was backed by two little-known advocacy groups: the National Federation of the Blind, which accepted $1 million from Diebold to build a new research institute, and the American Association of People With Disabilities, which pocketed at least $26,000 from voting-machine companies."

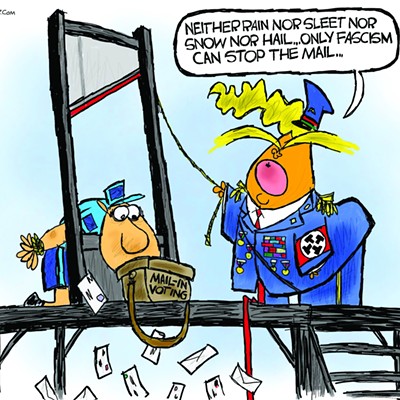

Besides privatizing the nation's electoral process and dumping millions of dollars into corporate coffers, HAVA is a hacker's wet dream. In a study released on Sept. 13, computer scientists at Princeton University created vote-stealing software that can be injected into a Diebold machine in as little as a minute, obscuring all evidence of its presence. They also created a virus that can "infect" other units in a voting system, committing "widespread fraud" from a single machine. Within 60 seconds, a lone hacker can own an election."

Besides the Princeton study, Rolling Stone references several others conducted by prestigious institutions and agencies all arriving at the same conclusion: electronic voting machines make the process of election tampering simple and quick.

Though manipulating programs, vote counts and memory cards are valuable and dependable tools in the hacker's arsenal, wireless technology delivers the promise of long-distance shenanigans. A memory card outfitted with a wireless antenna could make hacking less detectable. For one thing, honest poll workers would have no reason to get suspicious if the polling place were free of Diebold employees lurking in the shadows only to emerge for occasional tinkering with the equipment.

Imagine the possibilities if electronic voting machines were equipped with wireless gizmos enabling offsite evildoers miles from polling places to get continuous readouts detailing the vote count. Since control of Congress rests in a few states where close elections are anticipated, fixing the outcome could easily be accomplished.

Should tampering be suspected, what recourse would American voters (not to mention losers) have? Well, none. A paper record of votes can easily be made to reflect electronic tallies, and ballots have been known to go missing. And because private corporations own the machines, only employees of those companies have access to the equipment. There are no independent, nonpolitical watchdog agencies entrusted with the task of verifying the machines do what they are supposed to do: accurately count votes.

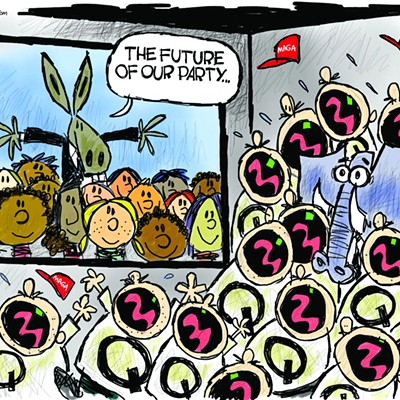

Which means that the electoral process, for all of its pre-technology flaws, is now--and for the foreseeable future--entrenched in the hands of a few private corporations and their Republican benefactors.