Now headquartered at a 150-acre ranch just a few miles from the Continental Divide in Montana, the nonprofit, nonpartisan organization has developed a bazillion-gigabyte databank about our elected officials--their bios, voting records, rankings by various interest groups and related fun facts. During the 2002 election cycle, staffers and volunteers tracked roughly 20,000 state and federal candidates, staffing a 24-hour toll-free hotline to answer political questions from curious voters. Project Vote Smart's Web site, which puts all the data at the fingertips of anyone with a modem, gets more than 3 million hits a day during peak political periods.

"We grow by 5 percent every election cycle, but it'll never get to where I thought it should be in my lifetime," says Richard Kimball, who founded the political clearinghouse after losing a U.S. Senate race to John McCain in 1986. "I think it's obviously necessary to provide at-your-whim access to accurate and abundant information about these characters, whether you're a right-wing conservative or left-wing liberal. Everybody's frustrated; everybody's dropping out of politics; everybody knows these candidates are abusing them with these commercials."

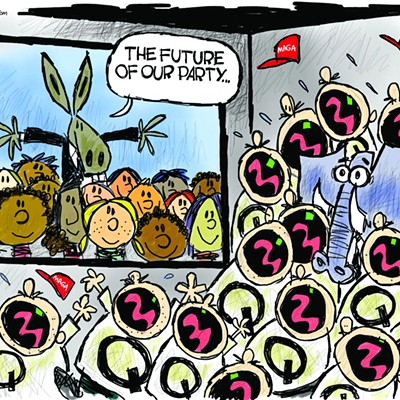

But Kimball and his staffers at Project Vote Smart are finding it increasingly difficult to persuade candidates to fill out the organization's primary survey, the National Political Awareness Test, or NPAT. A painstakingly detailed exam developed by political experts, the NPAT uses dozens of questions to gauge a candidate's position on topics ranging from abortion to tax policy. In 1996, nearly three out every four candidates were willing to fill out the questionnaire; four years later, less than half participated.

As one candidate put it, "I don't answer my mother's questions--I am certainly not going to answer yours."

Kimball lays the blame on Democratic and Republican party officials, who fear the NPAT will become one-stop shopping for opposition research and dilute the candidate's own message. "The parties clearly have these strategies that are now employed by the candidates," he says. "We've got evidence of it in about half the states around the country."

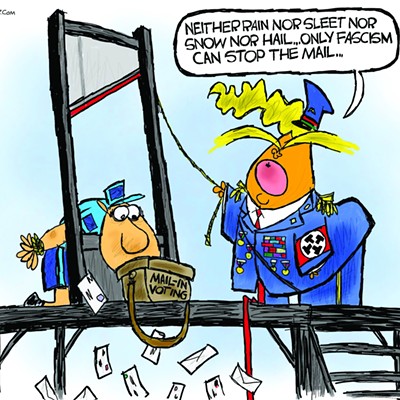

But the reluctance of candidates to lay out positions "is slowly eating away at the very heart of democracy," says Kimball. "It's very difficult for citizens now to get the one thing that was considered most crucial by the Founding Fathers, and that was their ability to acquire abundant, accurate, factual information about those people who want to govern."

Here in Southern Arizona, Congressman Raúl Grijalva didn't respond to the questionnaire during his campaign last year. Congressman Jim Kolbe did reply, along with two other members of Arizona's eight-man House delegation: John Shadegg (R-Dist. 3) and J.D. Hayworth (R-Dist. 5).

U.S. Sen. John McCain filled out the questionnaire, while Sen. Jon Kyl didn't.

Hank Kenski, director of Kyl's Southern Arizona office, says his boss declines to fill out most surveys, although he made an exception for the Arizona Republic questionnaire in 2000.

"We refer people back to our Web site," Kenski says. "We have nothing to hide. He is a known quantity on every issue."

Kenski, who moonlights as a professor in the UA's Communications Department, was a member of Project Vote Smart's founding board. He has helped the organization with various projects, from assembling issue briefs to helping develop the National Political Awareness Test, which "does way too much, quite frankly. We always advised them it was too long."

Kenski isn't surprised that politicians are wary of the NPAT.

"I think people get screwed over quite a bit," he says. "You can take specific things and pull them out of context. From the perspective of the office holder, the fear is, 'I want to control my message. You can vote me up or down, but I want you to vote on my message.' With a lot of this stuff that's out there, they don't control the message."

Kenski says Project Vote Smart still serves several useful purposes, such as helping people research voting history, but the advent of the Internet has put a lot more information at the fingertips of the average voter.

"The culture and the politics have changed," Kenski says. "When Richard started out, it was hard to get a lot of voting records and material. I think it's more accessible now."

Kimball argues that Project Vote Smart's questionnaire provides a clear, simple breakdown of a candidate's positions.

"I'm not saying the information isn't there," he says. "That's what Project Vote Smart does. It goes out and collects the information. And it's hell to collect information about these people. It is not clear in their messages; it is not clear in their commercials; it is not clear in their newsletters, and it's not even clear in their voting record. Congress has designed over the years these ways of making key votes buried in legislation, and you have to be a political scientist of some significance to wade through voting records and find out what's happening.

"If Hank Kenski is right, it says something bad about democracy," Kimball adds. "It means that people are well-educated, they are well-informed, they do know how people stand on the issues, and they've decided not to participate."