They found plenty, including a Miles Conrad encaustic abstraction at Davis Dominguez and a piece of pungent political art by Paco Velez at Raices Taller that skewered President Bush's Iraq war.

But at Santa Theresa Tile Works, they found something altogether different.

A young Turkish-Iraqi artist sat placidly at a table, painting time-honored Middle Eastern designs on ceramic tiles, their curling flowers, vines and trees intended to evoke the spirit of Muhammad and Allah. Through an interpreter, Morad Jasim told startled trendies that his Turkish designs date back at least to the 16th century, the days of the Ottoman Empire.

"My designs are very traditional," he said. "This is classic Ottoman art."

How did this refugee from the maelstrom of the Middle East land in Tucson's coolest arts neighborhood?

He's not one of the 2 million Iraqis who have fled the current war, and whose plight is starting to get international attention. His story begins back in Saddam Hussein's Iraq in the 1980s, and detours through Turkey before starting its Tucson leg almost two years ago. But it was just this spring that tile artist Susan Gamble got a call about him from a local refugee-resettlement office.

A coordinator at the International Rescue Committee told her he had a young refugee who needed a part-time job. Jasim was an experienced tile worker, and the agency hoped Gamble could make room for him in her Santa Theresa studios.

Gamble was intrigued. A well-known tile artist who's won numerous public commissions for her creative work--her multicolored "Plaza Arches" lining the Santa Cruz River Park are probably her best known in Tucson--Gamble hires workers to make her trademark glazed tiles in a production line. She liked the idea of helping out somebody displaced by the chaos in the Middle East.

"I wanted to seem hospitable as an American," she says. "I want people to think there are nice people in Tucson."

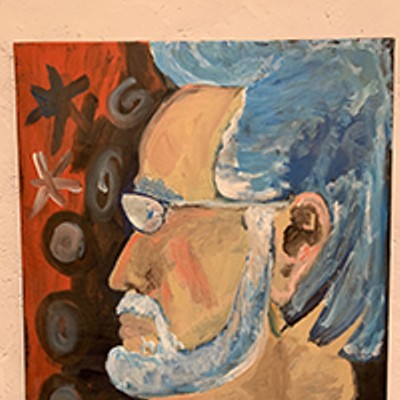

So she invited Jasim to come by. But when he showed up at her studio-gallery with samples of his own artwork, Gamble was astonished: Jasim's gleaming painted tiles were the work of a talented artist.

"He has a gorgeous hand," she exclaims. "It's very well done."

So much so that Gamble refused to hire Jasim to do the repetitive work in her studio. Instead, she told him she wanted to take him on as a gallery artist in his own right.

Now Jasim, who at 23 has already had to make his way in three separate countries, regularly has works on display at Santa Theresa.

"It's very traditional," Gamble notes. "As a potter, if I were in Turkey, I'd buy that stuff up like crazy. It's good."

Morad Jasim lives and paints in an apartment in midtown Tucson, in a building filled with international refugees. Outside, a couple of African kids are jumping in the pool on a blistering hot day, while a teenager in a hooded sweatshirt listlessly steers his bike over the courtyard grass.

If it's quintessential urban-American low-income outside, it's cool and distinctly Middle Eastern inside. Morad's mother, Shlir, dressed in veil and long skirts, bustles around with refreshments. On my first visit, she offers soda and fruit juice, then a plate of cut-up melon and apricot, and finally sweet tea in a tiny glass cup. Next time, it's orange juice, baklava--prepared by Morad, she says, smiling, speaking in the Turkoman dialect--and, inevitably, another glass of sweet tea.

She's created a Turkish ambience in the tidy apartment. Visitors and family members alike take off their shoes when they enter. Her son's painted Ottoman ceramics are displayed everywhere--above the couch, on a wall of shelves at one end of the living room--radiating their bright blues, reds and greens out over the standard-issue beige carpets and couches.

Morad sits on one of the sofas, near his brothers, Mohammad, 30, and Ahmed, 21. He's shy and not too confident about his English, though he's studying the language in the Pima Community College Adult Education program. His brothers often jump in to translate.

Though the other two favor the sciences--Mohammad trained as a pharmacist in Iraq, and Ahmed hopes to study the same discipline at the UA--Morad takes after their artist father, Abdullah. (Their three sisters are still overseas: an art teacher in Germany, and a lawyer and a translator still in Turkey).

A tile artist in his own right, Abdullah taught art in the family's native Iraq, where they lived in the northern city of Erbil, in a heavily Kurdish region just south of Turkey.

"We left because of life in Iraq," Morad says simply.

The Jasims are Iraqi citizens, but ethnic Turks--or Turkomans--who speak a dialect of Turkish. They're proficient in the majority language of Arabic as well as in Kurdish, but as members of a minority group, they were subject to persecution. The better-known Kurds far outnumber the Turkomans in Iraq--Turkomans make up less than 5 percent of the Iraqi population of 27 million.

Turkomans and Kurds are at odds with each other, in part because of the enmity between the nation of Turkey and the Kurds, but they share at least one trait: Neither is Arab. Notorious for his slaughter of the Kurds, Saddam instituted an Arabization policy that targeted both groups. In the 1980s, the Iraqi constitution officially banned the Turkoman language.

Morad's childhood was a dizzying blur of wars. He was born Oct. 1, 1983, while the eight-year Iraq-Iran war was raging. In 1988, when he was 5, Saddam gassed thousands of Kurds. Saddam invaded Kuwait in 1990, when Morad was 7; the following January, U.S. forces launched Desert Storm.

That brief war was followed by a Kurdish uprising against Saddam, and then sporadic fighting broke out between two Kurdish factions. In 1995, the year Turkey staged raids on Kurdish camps in northern Iraq, the Jasim family finally fled to Turkey. Morad was just 11 years old.

As his brother Ahmed says, "It's not a good situation in Iraq, always war, war, war."

Their older brother, Mohammad, cuts off the conversation, saying they don't like to talk politics, even now.

"The economy was bad," he offers. "And they don't like Turkoman people in Iraq. They don't give you anything. Our father made the decision to go."

Despite the chaos of his childhood--or perhaps because of it--young Morad was soon entranced by an art form that celebrates nature and spirituality. In a poetic artist's statement that he prepared with Gamble's help, he writes, "Among the many flowers shown in Turkish cini (tile) are the rose, dianthus, tulip, peony, hyacinth, plum flower and pomegranate flower."

Some of his patterns date to ninth-century Anatolia. Wreathed in flowers, swirling stems and vines, the designs not only suggest the plant life of the region; they're laden with Islamic symbols. The tulip symbolizes the spirit searching for Allah. Flowering trees represent heaven, and cypresses represent patience.

The rose is a frequent motif, because "it is believed that the Prophet's message of love and beauty are carried by the fragrance of roses."

Traditionally produced in the Turkish cities of Kütahya and Iznik, the decorative tiles adorn mosques, villas, bathhouses and other public buildings. In the home, they appear as vases, lamps, plates and wall decorations.

Morad came to this lofty tradition at a tender age.

"I started art at 12," he explains.

After getting a permit to leave Iraq, the Jasims--mother, father and six children--went to their ancestral homeland. (Abdullah's mother had been a Turk from Istanbul.) They settled in the powerhouse tile city of Kütahya in western Turkey, by chance near the studio of Mehmet Kocher, a noted tile artist.

"Our neighbor taught me," Morad says. "I worked with him for 4 1/2 years. Then I started by myself. Sometimes I make classic designs, and sometimes what I make up. But classic is better."

To demonstrate his technique, he repairs to his Tucson "studio," a small desk in his sparse bedroom. Small pots of paint, in the traditional colors of blue, turquoise, red and green, are lined up, in between brushes and drawing tools. Normally, he says, it takes him 10 hours, start to finish, to paint one of his plates or tiles.

First, he draws freehand in pencil on stiff paper, taking many of the designs from books he brought to the United States from Turkey. He's a gifted draftsman, and steadily, surely, he traces out a long, curving stem and flower petals.

When he's satisfied with a drawing, he makes it into a stencil--using a needle, he punches out thousands of tiny holes along the lines of the drawing. This stage is perhaps the most tedious, but the stencils are reusable, and Morad can do other things while he wields his needle.

"I can listen to music, watch TV. I can concentrate. It's fine."

Next, he transfers the drawing to the plates and tiles, which he purchases ready-made. He pours ash inside a piece of porous cheesecloth and arranges the stencil over the ceramic piece. Pulling the cloth into a tight ball in his fist, he rubs the ash across the paper. Miraculously, the lines transfer through the holes to the tile, and the complete drawing appears on gleaming white porcelain.

At last, he begins to paint, first tracing the outlines of the drawing, then filling in the centers of, say, pomegranate leaves or sailing ships. The water-based paints derive from jewellike stones: the reds from coral; the greens from malachite, turquoise and emeralds; the dark blues from lapis lazuli.

"Most of the colors, I just paint," he says, laying down long strokes with a thick brush. But the blues, so characteristic of Turkish tile, get special treatment. "The blues, I make in dots." He painstakingly stipples the blues in tiny dots, Seurat-like, with a minuscule brush that looks like a pen.

By 17, he'd completed his apprenticeship with the tile master and went into business for himself. He started making a name for himself, and he has the newspaper clips to show it. By 19, he was invited regularly to international art fairs showcasing the traditional arts of the Middle East. He traveled to Dubai, Syria, Jordan, Qatar and Lebanon. Sometimes he was invited abroad as a guest teacher.

"I taught two months in Beirut," he says. "I taught in a factory of 70 girls and men. They wanted to open a business like this in Lebanon. ... Beirut was peaceful at that time."

In Kütahya, his work was sometimes shipped overseas, and he was well known enough that customers sought him out. Morad recounts their surprise when they'd find that the up-and-coming tile master was a teenager.

"'Where is Morad?' they'd say. 'I am Morad.' 'No, you're too much young!'"

But life was not so good for the other members of the family. They couldn't get work permits, just as today's crop of Iraqi refugees are not permitted to work in many of the countries where they've fled. After spending 10 years in Turkey, the Jasim family finally managed to get through the burdensome process of being declared refugees by the United Nations, and they were accepted for resettlement in the United States.

Why did Morad leave just when his art career was starting to take off?

He answers simply: "My family was coming here."

On Sept. 29, 2005, the Jasim family, minus the three daughters, stepped off a plane in Tucson.

"It was very difficult," Mohammad says. "It was hot; we couldn't speak the language."

And, adds Ahmed, "We didn't know anybody."

The Jasims are not the only refugees to find themselves unexpectedly in the Old Pueblo. Every year, 600 to 700 refugees from all corners of the globe are resettled here. Lately, says Johan Lahtinen, a former IRC staffer who worked with Morad, the dispossessed are coming from Somalia, Sudan and Liberia.

A population of Meskhetian Turks from Uzbekistan are already settled in an apartment complex in midtown (see "An Area of Safety," Currents, Nov. 16, 2006). But the Jasims, Lahtinen says, are the only Turkomans he's worked with.

Still, some of their countrymen--though not Turkomans--are already here.

"Tucson has an Iraqi community of around 500 people," says Rachel Lau, acting executive director of IRC Tucson. They're Iraqi refugees who were settled here some years after the first Persian Gulf war, and they've made a good adjustment. "They do really well. They bring strong families. One Iraqi who just got his citizenship speaks Spanish as well as English."

But the plight of Iraqi refugees from the current war is turning into an international crisis. Some 2 million have fled the fighting in their homeland, crowding into cities in the small countries surrounding Iraq and straining resources, Lau says. Turkey, Jordan, Syria and, to a lesser extent, Lebanon and Egypt have all been taxed with an "urban refugee problem." As the Jasims found in Turkey, the countries don't permit the refugees to work, for fear that they will settle permanently.

Within the last year, the U.S. Congress authorized the president to offer refuge to some 7,000 Iraqis, but so far, "not even 500 have been given slots," Lau says. Critics believe Bush has failed to act because accepting refugees would be an acknowledgment of the failure of his Iraqi policy.

Just last week, an international conference in Jordan called on other nations, particularly the United States, to share the burden. Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass, introduced a bill that would offer a fast track to Iraqis who have worked for Americans in Iraq, and as a result are being targeted and killed by insurgents.

Eventually, Lau believes, at least some of these Iraqis will likely end up in Tucson.

"People are realizing it's a huge problem, the mess we made," she says.

There are two good reasons the U.S. funnels so many refugees to the Old Pueblo: low rents and entry-level jobs.

"Housing is relatively cheap here," Lau says. "And people can become self-sufficient here, working in the hospitality industry. There's a good number of service jobs."

The goal, adds Lahtinen, is "to make them self-sufficient."

Refugees who make it all the way to the Tucson International Airport have already demonstrated extraordinary self-sufficiency. After suffering the horrors of war or persecution in their own countries, they must go through a "long, meticulous process overseas," Lau says.

First up is the task of persuading the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees that they have been targeted because they're members of a particular political, religious, racial or social group, or that they're fleeing a war. Once OK'd by the United Nations, they jump through assorted U.S. hoops, undergoing through security and health checks before getting the go-ahead to board an American-bound plane.

If they have family or friends living in the United States, they'll join them in their cities, but many know no one. Like the Jasims, these people are randomly assigned to a place that is a complete unknown. Four agencies handle the resettlement work in Tucson: the IRC, Catholic Social Services, Lutheran Social Ministry and Jewish Family and Children's Service, where Lahtinen works now.

But the agency workers do their best to make the refugees feel at home.

"We pick them up at the airport," Lau says. "We've already set up the apartment, complete with plates, cups, couches, clothes. We know their ages and gender--we have places where they can pick clothes from a storage unit. And we give them a meal."

The Jasims, talking in their living room, remember the kindness of the agency workers.

"They had the house for us," Ahmed says. "And they found jobs for us."

The refugees are eligible for a variety of benefits paid for by the state and federal governments, including food stamps and medical care. They're issued Social Security cards and are legally permitted to work in the United States. Most go to work as soon as possible.

"We see 90 percent self-sufficiency after four months," Lau says proudly. "It's not easy."

The Jasims are typical. Mohammad is studying to get an American pharmacy license, but in the meantime, he works at American Home Furnishings. Ahmed bakes rolls for eegee's while planning his application to the UA. And Morad is concentrating on growing his art business.

"He came to this country with his talent," says Lahtinen, who specializes in micro-enterprise, or helping refugees set up small businesses. "My goal was to get him reoriented to the business climate here, and help him figure out where to sell his stuff. My approach is to find out their talent and hook people up with mentors."

Lahtinen enlisted a UA Eller MBA student to help set up Morad's Web site (

www.moradceramic.com ), which he hopes will be up in another month. A UA undergrad, Jacqueline Lemieux, a member of the Students in Free Enterprise club, volunteered to help Morad negotiate the American market.

"I worked with Morad all year," she says by phone from her home outside Seattle. "His favorite thing is beautiful vases that sell for $2,000. But we encouraged him to sell $50 items, that people are more willing to buy. And I'm trying to get him in higher-end shows. He has gone to Phoenix a few times and sold $300 worth of goods."

He had a booth at Tucson Meet Yourself last year, and is scheduled for another one this year, Oct. 12-14. At a Christmastime ethnic fair that Lemieux helped stage on the UA Mall, professors and students flocked to buy Morad's exotic handmade wares. "He sold $800 worth of goods," Lemieux says.

But a repeat event in February was something of a washout. A fierce wind toppled some of Morad's plates--the ones that take him 10 hours to make--and broke them into bits. But still he persists, recognizing that it will take time for him to build up his reputation here.

"Two or three years for me is hard," he acknowledges, but he's willing to put in the effort.

Lahtinen says Morad's optimism is typical of the refugees he's worked with.

"I've been in this business three years, and the human spirit of resiliency amazes me on a daily basis. Many have survived atrocities. They often have horrendous backgrounds. But these people have the inner strength to continue."

Gamble, the gallery owner, believes that art has given Morad a kind of life raft. As an artist herself, she says, "I feel a kinship with a potter or a decorator. That's my tribe. I understand him even if we can't communicate. If were in another culture, that's where I'd find my toehold, in art."

And that's what Morad Jasim has done. On the back of his newest plates and tiles, he has a new signature line. It reads: "Hand Made. Tucson AZ. Morad Jasim."