IT SEEMS THAT if a violent film is more intelligent than the average critic, the average critic will savage it with an unaesthetic, moral critique (e.g. Fight Club), whereas if the film is reasonably stupid, it can have excessive amounts of violence without coming under ethical assault (e.g. virtually any action movie made in the last 10 years).

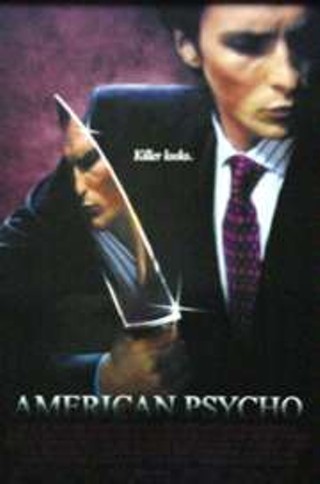

American Psycho, being a good bit smarter than the Michael Medveds of the world, has, of course, been criticized because it contains a few violent scenes. It also contains a scathing look at America in the '80s, some wickedly black comedy, and one of the best lead performances in recent memory.

The opening credits are shot over a white background, with drops of what appear to be blood running down the screen. The camera tilts and reveals that it is not blood, but a raspberry sauce being dripped onto an over-decorated nouvelle cuisine dessert, which is being served to a group of young businessmen.

It's the late '80s, and nothing symbolizes the hollow decadence of that era like nouvelle cuisine: nearly empty plates of food that are overpriced for the sole purpose of being overpriced.

As dessert is served, Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) is correcting an associate for making an anti-Semitic comment, but it's unclear whether or not he's joking, making a note on business ethics, pretending to be sensitive, or is actually disturbed by this. For Bateman, there is no distinction between irony and sincerity. He speaks every line as though he's the pitchman in a commercial for fat-free dressing. "I'm just saying let's cool it with the anti-Semitic remarks," he says, smiling with lips closed, as he takes a bite of his orange truffle duck breast sorbet.

Bateman is the anti-hero of American Psycho, a man who works at an undefined firm, doing an undefined job, and who can't seem to decide if he exists.

He comes into the office each morning to make dinner and lunch plans. His desk contains nothing but a date book (for meals) and a Zagat restaurant guide. His secretary gives him messages, all of which relate to meals and dates. He apparently does nothing, and is well paid for it.

He and his associates spend their time comparing business cards: one has Forte typeface on eggshell white; another has Garamond light on eggshell, another is Lucida on herringbone. Each is, of course, just plain type on a white background, and each is scrutinized to see if its plainness is the best. Rage and envy ensue when one card is deemed more tasteful than another.

Bateman dates a blank woman (Reese Witherspoon, doing an even emptier take on her empty character from Election) and sleeps with her insensate friend (Samantha Mathis). He tells rehearsed jokes in order to hear the rehearsed laughs of the friends he has no attachment to. And at the end of each day, before going home to his starkly modern apartment, he stops off and kills someone, just to take the edge off.

What sets Bateman apart from his fellow hollow men is that he kills the homeless in a hands-on way, with a knife. While the others make callous comments about suffering in the world ("what about Sri Lanka, where all the Sikhs are killing the Isrealis?"), Bateman does something about it, at least insofar as he adds to it in a direct manner.

Bateman is also a fan of the most commercial pop music, and as he prepares to kill he'll often give his victims an extended speech about the artistic merits of Huey Lewis or Phil Collins or Whitney Houston. "Huey Lewis and the News' early work was too New Wave for me...but with Sports they really came into their own. Nothing exemplifies this better than the song 'Hip to Be Square'...," he extols, while hacking an associate up with an ax.

Of course, first he covers his expensive suit with a raincoat, covers the polished wood floor of his apartment with newspaper, and selects the finest ax money can buy.

While this kind of shallow materialism marks the surface of all his business cronies, at least Bateman is aware that there's nothing underneath it. "I don't seem to exist...," he says, as he applies an apricot pit facial peel while preparing to do his morning crunches.

All of this comes through in the very careful directing and scripting of Mary Harron, who adapted Brett Easton Ellis' critically maligned novel into one of the best films of the year.

Unlike the recent spate of new golden age films that have been appearing in theaters (Fight Club, American Beauty and Three Kings were the most prominent examples last year) there's no sense of redemption in American Psycho. "My confession means nothing," says Bateman. He gets no closer to his "true self" because he doesn't have one. While American Psycho's view of humanity is bleak, it succeeds in being funny and insightful in the way it deals with the excesses of superficiality, and its equation of senseless acquisition with senseless violence.

Summing up the narrowness of his life, after disposing of the body of a friend, Bateman goes to his victim's home, and as he enters it, he narrates, "I panicked....I realized that his apartment was nicer than mine."

There is no darker night of the soul than the one that comes when you realize you've killed someone whose tastes are more refined than yours.

American Psycho is playing at Century El Con (202-3343), Century Gateway (792-9000), Century Park (620-0750) and Foothills (742-6174) cinemas.