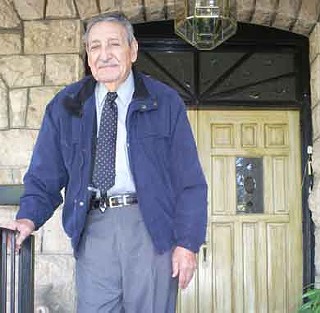

Raúl Castro, the former Arizona governor, opens the front door of his Nogales home even before I can ring the bell. He's been waiting behind those grand wood doors.

Castro is 93. Am I wrong to think that old people, those of a certain generation, those who've accomplished things, are just this way? Punctual. Organized. Not a moment to waste.

"Come in," he says. "We'll talk in the living room." Because he came up before the ubiquity of blue jeans and open collars, he's dressed for the occasion, too—dark slacks, powder-blue shirt, a tie knotted tight to his neck and a zipper jacket to quell the morning chill that settles over the border this time of year.

My interest in talking with Castro isn't to write a look-back, although we do spend quite a bit of time talking about the prominent characters from his past. Mostly, I want to hear what Castro has to offer right now, today.

In May, Texas Christian University Press published an autobiography, Adversity Is My Angel: The Life and Career of Raúl H. Castro, co-written by historian and author Jack L. August Jr. The title is a nice play on words, but it has a literal meaning.

From his earliest days in the Mexican settlement of Pirtleville outside of Douglas, dirt-poor, scouring the desert for mesquite beans to help feed the family's 11 children, adversity has followed Castro like a guardian angel. It has been his motivation.

Every Arizona school kid, as a condition of graduating eighth-grade, should be required to read Angel and write a paper—all the words spelled correctly, the grammar impeccable—on what it means. They would find many lessons, about the importance of education, patriotism, the power of will, the necessity of never giving up.

"In all my 93 years, I've heard people complain about what can't be done," says Castro. "I wanted to write this book because I got tired of hearing the griping. This is a great country, a country of opportunity. But you can't sit back and expect others to do the work for you. You have to be active and participate."

The book's most potent message is about overcoming obstacles such as discrimination. Castro's story proves what a pitiful obstacle discrimination is: He faced the worst of it, but it shrank to irrelevance before the force of his ambition, the strength of his values and the locomotive of hard work.

Not only did he become governor in 1975—still Arizona's only Hispanic governor—but he also served as Pima County attorney, a Superior Court judge, and American ambassador to El Salvador, Bolivia and Argentina.

But all of this came within a whisker of not happening.

If he'd been arrested in that Los Angeles train yard in 1940 ...

If he hadn't fallen into that garbage hole, hiding him from the police ...

We're sitting on Castro's plush white couch, surrounded by wife Pat's collection of antiques from around the world, and I say: "Governor, tell me about your years as a hobo."

In 1939, after graduating with a teaching degree from Arizona State Teachers College in Flagstaff, now Northern Arizona University, Castro returned to Douglas to find a job.

But no one would hire someone of Mexican descent to teach. He tried for civil service jobs, too, with immigration, the FBI, the post office, and the result was always the same: He easily passed the written exam, but when he showed up for the oral exam, and it became obvious he wasn't blue-eyed and blond-haired, Castro was sent on his way.

"It bothered me a great deal," he says. "Here's the U.S. government participating in this discrimination."

Unable to find work, he decided to leave Douglas. His mother, Rosario, called a family meeting. Two of his brothers said the family should return to Cananea, Mexico, the copper-mining town where Castro was born in 1916.

His father, Francisco, a Basque Mexican, had died in 1928. Francisco never went to school. He spent his early years as a pearl diver on the Baja Peninsula and later was jailed for union organizing in Cananea. Authorities eventually relented and agreed to release Francisco, but only if he left Mexico.

Early in 1918, the Castro family entered the United States at Naco, south of Bisbee. They crossed legally, as political refugees.

At the family meeting, Rosario spoke up: "Don't forget, we came to this country as refugees and were accepted. We owe this country something. We have a responsibility. If any of you want to leave, there is the door."

No one left. Alfonso, one of the Castro brothers who argued for returning to Mexico, later joined the U.S Army, fought in four wars and retired a colonel. He died with shrapnel all through his body.

Making good on his desire to depart Douglas, Castro hopped a freight train out of town and became a hobo, traveling the country by rail. He did stoop labor on farms in California, Idaho, Montana and Oregon.

Alongside Mexican and Filipino women, he worked 12 hours a day clearing sugar-beet fields for $7 an acre, and slept under trees. At fairs and carnivals, he boxed to earn $50 here, $100 there.

Castro usually wore coveralls when he traveled. But he also carried his NAU letterman's sweater with three As on it, which helped him get rides while hitchhiking.

In Ogden, Utah, he hopped a freight to Los Angeles. When it pulled into the yard at sundown, the L.A. police were waiting to chase the hobos emerging from the cars. In those days, a vagrancy bust meant 15 days in jail.

When Castro jumped down from the train, he fell into a hole filled with garbage and stayed there, hidden from the police. After 45 minutes, the yard was empty, and he crawled out of the hole wearing his college sweater, brushed it free of garbage and went on his way.

"If I'd been arrested that day, I never would've become governor of Arizona," says Castro. "With an arrest record, I couldn't have become a lawyer or held elected office."

The life forced upon him didn't send Castro to despair. He found important lessons in it.

At boxing matches in Pennsylvania, he heard the crowd shouting, "Kill the dago! ... Kill the wop!" In those days, there were few Mexicans in the East, so the crowd assumed he was Italian.

In Minnesota, Castro encountered hostility toward Finnish people from Swedes and Norwegians. He saw signs on the street saying, "We don't rent to Finns," and, "No Finns wanted."

"It made me think, 'This is a crazy world,'" Castro says. "But I quit feeling sorry for myself, because I saw somebody else being picked on besides me. It wasn't just Mexicans, and it was true everywhere I went. It gave me encouragement, in a sense."

Castro's break—the start of a work life spent wearing a suit and tie rather than swinging a pick in the mines—came in 1941. He landed a job at the American consulate in Agua Prieta, Sonora, across the border from Douglas.

"I felt it was time for someone of Mexican descent to excel, to become a professional," says Castro. "I wanted to get away from the common slogan in those times, about the dumb Mexican and the dirty Mexican. I didn't want to be dirty, and I didn't want to be dumb."

Seven decades later, the young college graduate who hid from the cops is still sought after, though for very different reasons. As we talk, his home telephone rings repeatedly, followed by the yapping of the family dog, Fabio, named after the romance-novel cover model who seemed to be everywhere a few years back.

"It's always like this," says Castro of the phone. "You should see my schedule."

Co-writer August says the extraordinary arc of Castro's life naturally attracts attention. Hollywood producers have already put out feelers about a movie.

But Castro is also terrific before audiences. August recalls a speech he gave a couple of years ago to a group of conservative Republicans from Scottsdale.

"Raúl got up and spoke for an hour with no notes, and here's a 92-year-old guy, and they were laughing and crying," says August. "He's so inspirational. Any Democrat who can get a standing ovation from those Republicans, my hat is off to the guy."

On the day after my visit, Castro will go to Tucson to pick up an award from the Daughters of the American Revolution, given to Hispanic Americans who have excelled. The week before, he was at book-signings in Flagstaff and the Grand Canyon, and he is a regular speaker at schools.

He can still drive, but prefers not to. He has someone chauffeur him around Arizona, delivering his message of hope and possibility. He feels so strongly that young people need to hear his story that he pays his own travel expenses.

Castro has always kept moving, feeling the push of ambition at his back. It comes from being lost amid a family of 11 kids. Mom Rosario, a midwife and curandera, a traditional herbal healer who sometimes took payment in cans of lard or live chickens, ran the house like a boot camp, never hugging her kids before bed.

Castro says this led to his difficulty in showing affection as an adult. As he grew older, he says, "I wanted somebody to care about me. I wanted recognition."

But Rosario inspired him, too, telling her son he could accomplish whatever he wanted. Young Raúl took it to heart.

"He always believed in himself," says August. "Like a lot of guys who run for office and lose, but keep trying and finally win, there's a sense of destiny to them. Raúl has that. He's a very competitive guy, and it has served him well."

Castro ran for Pima County attorney in 1954, over the objection of Mo Udall, the future congressman and presidential candidate.

Udall, the sitting county attorney at the time, one day summoned all of his deputies, including Castro, to a meeting. He told them not to bother running for county attorney in the upcoming election, because, as Udall said, he had handpicked his successor and was certain the friendly press wouldn't object.

Annoyed, Castro left the meeting and returned to his office. An hour later, Udall came and asked why he'd left. "I said, 'Mo, I have news for you,'" says Castro. "'I'm going to run for county attorney, and obviously, you think you're the kingmaker, and that's all there is to it.'"

The two traded words. Castro stood up angrily. "Look, if you don't like it, I'll knock the hell out of you," he said, and as he began to storm around his desk, Udall walked out.

Castro won the election. He later won another election as a Pima County Superior Court judge. In 1964, after turning down an offer to become U.S. Attorney for Arizona, which Castro thought was a step down, he let it be known he'd like to be an ambassador.

Arizona's powerful Sen. Carl Hayden took the idea to then-President Lyndon Johnson, who agreed.

But LBJ asked if Castro would be willing to change his last name to Acosta, Rosario's maiden name. Johnson feared Americans would confuse him with Cuban dictator Fidel Castro's brother, defense minister Raúl Castro.

Castro refused. He told Hayden, "You tell the president I like my name."

LBJ relented, and Castro got the El Salvador job. He went on to become American ambassador to Bolivia and Argentina, the latter posting ending in 1980.

Pride has always run deep in Castro, as has his sense of responsibility.

While attending college in the 1930s, he'd return to Douglas in the summer to work in the smelter and help organize its union. As a former farm worker himself, he knew and admired César Chávez, and considered his objectives noble and good.

But he's troubled by modern demonstrators who take to the streets waving Mexican flags.

"I disagree with that," he says. "'Viva Mexico!' That's for the birds! If you want to wave a flag, wave the American flag. Suppose I went to Hermosillo and carried the American flag. They'd shoot me in five minutes. I'd be dead. I don't believe in shouting and breaking windows. We have to unite."

He's always been a conservative Democrat who sees education as the equalizer.

At the same time he served on the Superior Court, Castro also was a Juvenile Court judge. The defendants, many of them Mexican American, were tough youngsters, drained of hope, who saw little reason to either follow the law or stay in school.

Castro would look down at them from the bench and say: "What do you think I am, English or Swedish? You think I came from a rich Anglo family? I was born in Mexico of poor immigrant parents. I picked cactus fruit in the desert for food when I was a child, and I've worked in the fields. But I worked hard, and went to school, and improved myself. Today, I am a judge. You can do the same."

Every Monday morning, the judge would check attendance records at Tucson, Pueblo and Sunnyside high schools. Absenteeism in those days was very high, and Castro says it was mostly Mexican children.

"In the evenings, I'd go to the parents and ask, 'Why wasn't Marguerita or Jose in school today?'" says Castro. "They cared less. Their aunt was sick, and they had this excuse and that excuse. Education was not a priority. Education? Who cares? Get to eighth-grade, get out, goodbye. It's gotten much better, but you'll find the absenteeism is still highest among blacks and Hispanics."

After Argentina, Castro and his wife returned to Paradise Valley, where Castro practiced law. By 1993, Pat had tired of battling Phoenix traffic and began scouting the state for a new home. She grew up in Wisconsin, was a widow with two girls when she married Raúl in 1954, and always appreciated Latin culture.

She chose Nogales. But her husband balked at returning to the border. "I said fine," recalls Pat with a laugh. "You can rent an apartment in Phoenix and come down on weekends. Now, he wouldn't live anywhere else."

Their elegant home, built in 1906, sits on a hill 75 yards from the border fence. The location gives the Castros an unobstructed view of Nogales, Sonora, where white-columned homes stand alongside laundry-line shacks, both clinging precariously to the hillsides.

The proximity of the international line makes the border war a fact of their daily lives. Two or three times a week, they hear gunshots. Down the slope from their back porch, there's a chain-link fence that illegal aliens climb and damage, requiring frequent repair work. And there have been nights when Drug Enforcement Administration agents have set up stakeouts in the Castros' garage.

But like many of those living on the border, they can't imagine being anywhere else. Pat certainly prefers Nogales to the different kind of chaos in Phoenix, just as she preferred the life of an ambassador's wife to politics.

When Castro was elected governor, they lived in a motel in Phoenix. They didn't have a home of their own until a radio-station owner donated one, in Paradise Valley.

"The first thing we read in the paper is, 'Why does a Mexican governor need a $350,000 house?'" says Pat. "That kind of thing got under my skin. I was delighted to leave for the perks you get as an ambassador, rather than the slights you get as governor."

Castro's resignation as governor still rankles. He served two-plus years before leaving in October 1977 to take the ambassador's job in Argentina. He felt he'd have more prestige and more ability to improve relations with Latin America if he represented the whole nation rather than one state.

"But the Hispanic community especially felt let down," Castro says. "They worked their butts off to get me elected, and I do have regrets about that."

Moving slowly but steadily, Castro leads me around the elegant old house on a tour—the back porch overlooking Mexico, the winding staircase to the second floor (now equipped with an elevator chair to make the trip easier), and by the front door, the first thing visitors see, an American flag.

As much as anything else, Castro is an American patriot. He calls the day he became a citizen one of the best of his life.

I think of my grandparents, two of whom were born in Ireland. They came to Boston legally, faced the no-Irish-need-apply signs, worked hard, assimilated, respected the laws and prevailed. Our stories are the same. They're stories of triumph.

And that's the main point Castro wants young people to understand—the infinite possibility this country allows.

"But they're motivated too much by self-satisfaction," he says. "They get a job at McDonald's or some restaurant and think that's enough. It isn't. The minimum isn't good enough. They need to sacrifice to make something of themselves, and too many of them don't think they can make it."

But if they hear his story, Castro is convinced they'll think otherwise.

In 1926, Arizona Gov. George W.P. Hunt came to Douglas for a Fourth of July celebration. He gave a speech at a park on Tenth Street. Hearing there would be free sodas, hot dogs and hamburgers, Castro and two of his pals attended. He was 10.

The boys gathered at the bandstand beneath where the governor, a legendary figure in Arizona politics and history, was speaking. Hunt was built like a beer truck. He wore a pith helmet and a white linen suit, and had thick glasses and a walrus mustache.

He talked about the opportunity America offered. "Anyone can become governor of Arizona," he thundered, then paused and pointed down at Castro. "Why, even one of those little barefooted Mexican kids sitting over there could one day be governor!"

Castro laughs as he recalls the event. "I didn't know what a governor was and couldn't have cared less," he says. "I was there for the hamburgers."

In 2002, Douglas renamed that park. It is now called Raúl H. Castro Park.