Fortunately, this year's election figures are expected to be considerably higher, because both major political parties, along with independent efforts, have been registering people all over the country. In Pima County alone, tens of thousands of individuals have been added to the voter registration rolls in the past few months, bringing the total by the early October cutoff date to an estimated 445,000--still only a little more than two-thirds of the eligible adult population.

The presidential race has fueled emotional rhetoric from all sides, pushing hot buttons and probably getting more voters to the polls. One potential result of all this interest could be the reversal of a steady decline in presidential voting since 1968.

Sitting with her two small children at the Reid Park dog run on a beautiful Saturday morning in September, 24-year-old Brandy Vasquez thinks for a moment before answering a question about voting. "I've never voted," she replies, "but I will this year. My future, and that of my kids, is at stake."

And Vasquez isn't alone.

"I've only voted a couple of times in my life," offers 51-year-old Dennis Lynch, as he relaxes outside the UA main library. "Most of the time, I didn't think it really mattered, and I didn't pay much attention. But the terrorist stuff was an act of war, so I'll vote this year. It's important."

Reflecting somewhat similar feelings, 37-year-old Candice, who didn't want her last name used, says: "I just got my voter registration card for the first time. The Iraq war and the deaths there, I guess, are what made me decide to vote."

Strongly held sentiments from all perspectives of the political spectrum are expected to drive up voter turnout next week, nationally as well as in Tucson. Some people are predicting that 80 percent of registered voters locally will weigh in at the ballot box on Tuesday.

Yet even with that scenario, changing our bad voting habits is going to take more than one intensely contested race. As long as so many people remain unregistered, the next president of the United States will be selected by barely one-half of the eligible population.

Meanwhile, in recent statewide and local races, the turnout has been much smaller, and the percentage of voters abysmally low.

So in a democracy, what's not to like about voting? With the enormous impacts that electoral decisions can have on people's lives from the national level on down, why do relatively so few people participate?

"Some people are disconnected from the way different levels of government operate," says F. Ann Rodriguez, Pima County Recorder. "There are so many different branches of government that impact people, whether they vote or not. Some people throw their hands up, saying they have two jobs or don't have time to study the issues. Some do not care. But regardless, somebody will make decisions for us, and every election is important, no matter how big or small, because we're impacted."

Tucson City Clerk Kathy Detrick suggests that there are numerous "little" reasons why people don't vote. But, "Non-voters don't understand how powerful their vote is. If they took the time to find out (about issues on the ballot), they can actually make a difference."

Based on survey results from 2002, the U.S. Census Bureau reports that non-voters give a long list of reasons for not participating in the democratic process, from being sick to being out of town.

One reason not shown by the Census Bureau, but distinctly possible, is illiteracy. With almost 20 percent of Arizonans being functionally illiterate, it wouldn't be surprising if they opted out of elections simply because they can't understand the ballot.

The national demographic profile of non-voters shows that men, younger people, members of minority populations, people with less education and singles are not as likely to vote as their counterparts. Annual income also helps define who votes, with the Census Bureau reporting: "Almost one-half of those who voted in the November 2002 Congressional election lived in families with incomes of $50,000 or more."

Why don't people vote in Tucson? Based on dozens of interviews with randomly selected respondents at five locations throughout town, the reasons given for not voting range from a distrust of government to a lack of knowledge about particular issues.

"Government hypocrisy is the reason I don't vote," says Dave Matheny. "They say one thing and do another, like with the medical marijuana issue." (In that case, Arizona voters supported a law allowing the use of the drug for medical purposes, but federal and state governments blocked its implementation.) From his perspective, 39-year-old Matheny thinks, "If you vote on something, that is the way it should be."

Brandon Quihuis also points to the behavior of politicians in explaining why he doesn't vote. "They say one thing, then do another thing," the 27-year-old says.

Robert DuPre, 77, has voted occasionally in his long life, but indicates he won't be doing so this year. "I'm not interested," he says. "You'd have to put a .38 to my head to get me to vote. I don't vote, because it encourages them (politicians)."

Says 46-year-old D.B.: "I don't understand the issues. I checked it out one time, and there was gobs and gobs of information, so I said, 'To heck with it.'" In reference to complex ballot propositions, he adds, "If you vote 'no,' it means 'yes.'"

Bobbi and Ramon Nez say they don't know why they don't vote. "I'm not really interested in the whole presidential thing," 18-year-old Ramon says, while his sister, who is 6 years older, adds, "I don't take the time to do it."

One young person (who wishes to remain anonymous) says he doesn't vote for medical reasons; he states that if he registered, he'd have to be on jury duty, and his psychiatrist has told him he shouldn't do that. (County voting officials indicate, however, that a letter from a psychiatrist would be sufficient to excuse a person from jury duty.) In comparison, a 51-year-old woman who was panhandling at a local grocery store said she didn't vote because she didn't know where to go.

Michele Convie, 55, gives another reason for not voting--she legally can't. Convie says she was sent to prison almost 30 years ago for possession of marijuana, and again in the 1980s. She would now like to get her voting privileges returned, but is finding the process difficult, time-consuming and expensive.

"For 18 years, I haven't voted," says Convie. She adds that when she got out of prison, "They never told me the process (of how to regain voting rights), just that I couldn't vote. It is a long process which is complicated and discouraging."

While most of these people are among the almost one-third of Tucsonans who aren't even registered to vote, those who are registered often don't show up at the polls anyway, especially in local elections. When asked why they vote in presidential contests and not others, those interviewed gave a variety of answers.

Erica Mortensen, 21, says, "If I knew more (about the issues), I'd vote more."

Shannon, 33, who declined to provide her last name, says, "I'm not sure why I don't vote more. I'm sort of embarrassed about that."

Sioux Megill listed a commonly heard reason: "I vote primarily in the presidential election," the 37-year-old says. "If there's a school issue, I vote. But often there is so much legalese, and we don't know what we're voting on."

Based on statements like this, the obvious question is: If unregistered people and those who sit out most elections did vote, would it change things? UA political science professor John Garcia thinks it would alter the focus, if not the policies, of political candidates.

"Hopefully, candidates would be more responsive," to issues that impact these new voters' lives, Garcia says. He mentions health care. "The discussion of health care coverage could change. Basic health care access and coverage are not given attention now. But having more people vote could put it on the table for discussion."

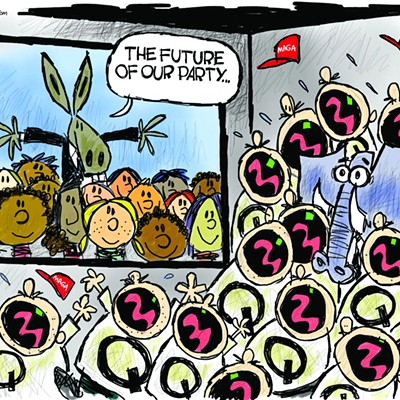

But that doesn't mean a major shift in American politics. "With a 10- to 20-percent increase in turnout," Garcia says, "a lot (of analysis) suggests there wouldn't be a clear-cut effect for one party or another."

John Munger, chair of the Pima County Republican Party, agrees with that assessment. "I don't think government and policies would change (if more people voted)," he says.

Pointing out that both major political parties have conducted aggressive voter registration drives, Munger says he doesn't know what more can be done to encourage more people to vote.

Democratic Party Chair Paul Eckerstrom, though, has some ideas. He would like to see a mid-week national holiday enacted as Voting Day. In addition, he believes free television airtime for debates should be provided before elections.

As for why people don't vote, Eckerstrom says, "We don't make it easy to vote, and Proposition 200 (the Protect Arizona Now initiative), if it passes, will make it even harder. I also believe some people don't think their vote counts because of the money interests in politics. But if everybody voted, the people with money would be outvoted."

Dave Stewart, office manager for the Green Party of Pima County, sees things differently. What surprises him is that voter turnout is as high as it is. Just being able to vote isn't enough, he believes. People need to have real choices.

"People don't vote because they don't feel there is an opportunity to change anything," he says. "Both major political parties represent the same kinds of interests, which discourages people."

To alter that situation, Stewart thinks people need to be given real choices, either from new political parties or within the major parties themselves. Plus, he thinks politicians and the media need to start talking about things that are important in peoples' lives, not superfluous issues such as military service in the Vietnam War.

"Drop that baloney and talk about issues," he emphasizes. "That will get people out. If people think their vote counts for something, they will turn out."

Short of supplying more political choices, analysis by the Census Bureau indicates that perhaps the most important factor in determining whether someone votes is whether they bother to register. One possibility to increase statewide turnout, therefore, would be for Arizona to make registration as simple as possible. To accomplish that in other places, six states now allow registration to occur on Election Day. The results appear to show that this policy increases participation.

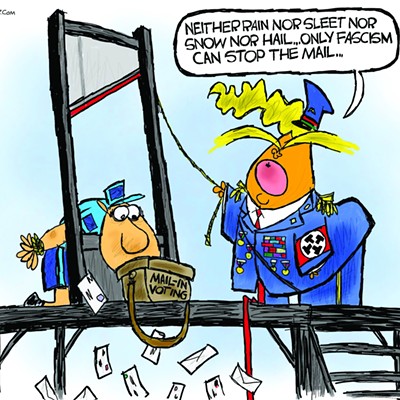

But Jan Brewer, Arizona's Secretary of State, doesn't look favorably on the idea of same-day registration. She thinks it could result in problems such as fraud.

"I'm personally uncomfortable with same-day registration," Brewer says. "It could lead to very uncomfortable situations, so I oppose it."

Another possibility is for the media to give additional coverage to all ballot questions and campaigns, not just concentrate on the high-profile races.

County Recorder Rodriguez, though, thinks that local news coverage of elections has helped boost turnout, as has the vote-by-mail program.

"We're fortunate with the amount of press we get to help get the word out," she says. "Vote-by-mail also helps, especially on the propositions. It allows people the opportunity to find out a little bit more (about the issues)."

City Clerk Detrick indicates she and other officials responsible for the voting process have talked about how to encourage higher turnout.

"The idea of trying to get people to appreciate the impact their vote has at the local level has been discussed," she says. "We could start with younger people in schools to give them an appreciation of the right to vote, which is actually pretty rare. We need to convince people it does matter, and I get frustrated because voting is so important."

As has been demonstrated this year, fierce competition in close races combined with hot issues also tends to encourage people to vote. These two factors, however, are often in short supply when it comes to many candidate choices and ballot propositions.

Politicians from both major political parties do their best to lock in as many so-called "safe districts" where, based on voter registration affiliations, the outcome is almost guaranteed. At the same time, these same politicians propose ballot propositions that are often complex and unclear. The result is that large numbers of people don't go to the polls because they are confused and don't believe their vote matters.

On the other hand, many Tucsonans agree with 22-year-old Justin Heckman, who says, "I feel I'm making some sort of difference (when I vote)."

Quite a few of those polled for this article, however, would also like to see some improvements made in the election process.

"Often, the way things are written is confusing," says 37-year-old Francisco Padilla. "I want both sides, but make it simple, so we can get what happens."

Qiana Kelly, at 20 years old, will be voting in her first presidential election next week. "There is a lack of information," she says. "It's so hard to do the research on my own, or know where to go."

Others also find information hard to find.

"Get the message (about the importance of voting) on TV, the radio and in the schools," suggests 18-year-old Melissa Norris.

Phyllis Garnett, 70, has been an off-and-on voter all her life. "I didn't have transportation, and I didn't see anyone to vote for." But beginning with last month's primary election, the 70-year-old Garnett insists she will be a regular voter from now on.

"Things are getting kind of hectic now," she says. "So I thought I should start voting again."

Franklin D. Roosevelt once said: "Nobody will ever deprive the American people of the right to vote except the American people themselves -- and the only way they could do this is by not voting." The question now is: Will next week's expected high turnout be an anomaly, or a sign of permanent change in American and local voting habits?