Supporters of a new initiative, No Taxpayer Money for Politicians, are expected to deliver more than 270,000 signatures to qualify for the ballot by the end of this week, according to Nathan Sproul, a Phoenix political strategist who is coordinating the effort.

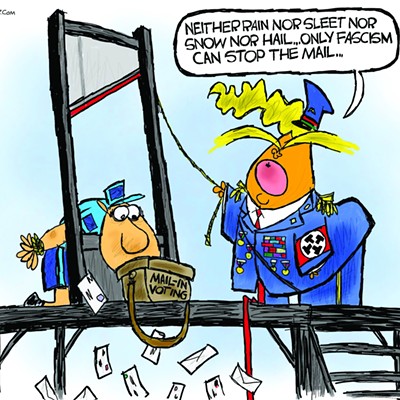

Clean Elections, a complex experiment in campaign-finance reform that provides dollars to qualifying candidates, wouldn't be directly repealed by this year's ballot proposition. Instead, the constitutional amendment would ban the use of public funds for the public financing of elections, which would essentially starve the system.

"We're putting forward an amendment to voters asking them a simple question: Should taxpayer money be used to fund the political campaigns of politicians?" Sproul says. "We think that overwhelmingly voters will answer that question with a 'no.'"

Sproul, the former executive director of the Arizona Republican Party, says that Clean Elections spent $13 million in 2002 to fund political campaigns.

"In a year when Gov. Napolitano is complaining that there's not enough money for all-day kindergarten, there's not enough money for health care for seniors and there's not enough money for middle-class tax cuts, it seems like funding the campaigns of politicians is one of the lowest priorities," Sproul says.

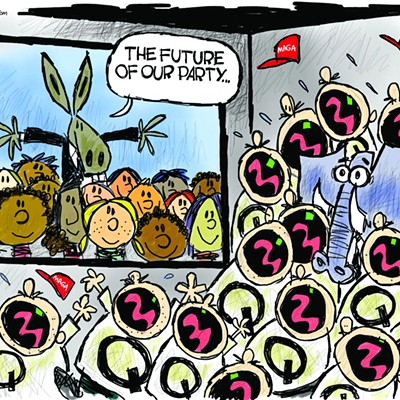

Supporters of Clean Elections have formed their own political committee, Keep It Clean, to campaign against the new initiative. Doug Ramsey, spokesman for Keep It Clean, says Clean Elections has provided an attractive alternative to politicians who dislike the traditional route of approaching special interests for campaign contributions. In 2002, seven of nine successful statewide candidates used Clean Elections, including Gov. Janet Napolitano, who received $2.254 million for her campaign against Republican Matt Salmon, who raised private funds for his campaign. More than a third of the Arizona lawmakers now in office have received public campaign funds.

Ramsey notes that while Clean Elections provides public funds to politicians, the majority of dollars given to candidates comes from a dedicated source created by the original proposition: a 10 percent surcharge on criminal and civil fines. He adds that the program was able to send a surplus of more than $5 million to the state's general fund after the 2002 election.

Democrat Jay Blanchard, the first candidate to file for Clean Elections dollars in 2000, says the program helped him pull off an underdog victory in a heavily Republican district in a Senate race against former House Speaker Jeff Groscost, whose political stock crashed after he masterminded the alt-fuel debacle that cost Arizona taxpayers more than $100 million.

As a result, the state Senate ended up split 15-15 between Republicans and Democrats, leading to a GOP moderate, Randall Gnant, landing the post of Senate President.

"Clean Elections offers people who don't have the financial resources yet want to participate a chance to run," says Blanchard. "I think the objections that some have, that some ne'er-do-well or some kook will get in and be able to run for office--I think our state is strong enough to withstand a few folks like that running for office."

Blanchard, who gave up his Senate seat in 2002 to run an unsuccessful statewide campaign for state superintendent of public instruction, says one flaw in the system is that it doesn't provide enough money to mount a vigorous statewide race for some offices.

Since public dollars aren't available for initiative efforts, both campaigns are using the old-fashioned method of collecting contributions from special interests. Although complete campaign finance reports aren't due until June 30, contributions greater than $10,000 must be reported immediately.

The early big contributors to the effort to cripple Clean Elections include $10,000 contributions from auto magnate Jim Click, legendary land speculator Don Diamond, homebuilder Bill Estes, billboard magnate Karl Eller, the Central Arizona Home Builders Association, Compass Bank and other representatives of the Growth Lobby.

Ramsey says the big-dollar donors "like the system where they contribute to candidates and then candidates do the things that they want them to do at the Legislature."

But Sproul says supporters of the new initiative are just concerned that taxpayer money is being wasted on political campaigns.

"The people who are supporting our campaign believe it's a poor prioritizing of dollars to spend that kind of money to fund the campaigns of politicians," says Sproul, who counters with a complaint that the campaign to support Clean Elections has been funneling its major contributions through various nonprofit agencies, including $91,000 through the Arizona Advocacy Network, to avoid leaving a money trail.

"They're not disclosing the names of their big donors," says Sproul. "It just strikes me as odd that a campaign that's saying, 'Let's keep it clean,' has endorsed that kind of a tactic to hide their donors."