Not that I couldn't write a scathing and pithy indictment of the health-care system; I'm just not going to. It would be like a gambler badmouthing the Mafia when he knows that somewhere down the line, he's going to wind up needing a short-term loan from Paulie Walnuts. Don't bite the hand that feeds you, and don't burn bridges you might need to cross later. That's my motto. Now and forever, amen.

And in an absolute sense, the health-care system isn't all that bad. That's what I was thinking a second after my asshole gelding launched me into orbit. I have never hit the ground so hard in my life, and I didn't think it was possible to hit it so hard short of re-entry from outer space. I knew my collarbone was broken immediately; I am not really sure whether I heard it or simply felt it. It helped that I'd broken the other one three years ago, so I had a point of reference.

What I didn't figure out until later was that the broken bone had skewered my lung, or, who knows, maybe the impact just ruptured it. In any case, my breathing machine was broken.

But I digress. Back to not writing about the health-care system. Fifty yards from the ranch and about 50,000 miles from the normalcy in which I'd started out that morning, I was thinking about the miracle of 911 and cell phones. I mean, if I lived someplace like Somalia or Uzbekistan, I could press 911 until the cows came home, if I had any cows, and no one would ever come. Of course, if someone did come, what could they do? Chuck me into a wheelbarrow and run around screaming and then give me some cheap rotgut made from fermented yak dung to take the pain away until I begged them to shoot me?

That's what I was thinking while also hoping the ambulance I could hear in the distance would move a little faster. I had begun to suspect I was lying in an ant hill.

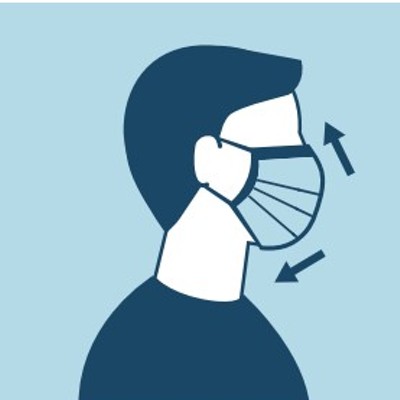

Hospitals are like jails, only with more pillows. All of a sudden, you're stuck in an enormous and baffling social situation in which you don't know the rules and from which there is no obvious escape. In my case, it was because after all the X-raying and CT scanning, I was tethered to a lung machine with about 5 feet of the same kind of plastic tubing I use at home to siphon water from our fish tank. A lung machine is a rectangular box that bubbles, and sometimes, it sounds like there is a teeny, tiny man in there forever gargling. The other end of said tube was inserted into my lung via my rib cage and all the nerves and flesh which happened to be in the tube's way. That box went with me everywhere, from the ER, to another part of the ER, then from one hospital room to the other.

It would have gone out the window with me, too, had I decided to jump. Not from the physical pain--I'm way too tough for that--but from my cellmate.

There's something I've always suspected, but shied away from admitting, because it's so horrible: There are some people who absolutely adore being sick. Any conversational gambit beyond, "What time is it?" elicits a catalogue of every physical travail these people have ever endured. When sharing a hospital room with one of these people, if they want to tell you every gory detail of their recent stomach-stapling surgery, then you're bloody well going to hear it. You're also going to hear about their gall-bladder surgery, their chronic acid reflux, their hemorrhoids, foot problems, high blood pressure, running sores, mysterious pain syndromes, misunderstood emotional problems and—especially--why their situation is about 100 times more dire than yours is, even though all they had was bunion surgery. In between these never-ending litanies, they complain about the breakfast menu, which features Cream of Wheat, because they're allergic to wheat, except, apparently, when it's in cake, which they must eat massive amounts of, from the looks of them. Then they start in on the ailments of every family member, all their neighbors and everyone else they've ever met.

Then their very best friend from Bumblefuck, Minn., flies in, and you get to hear it all again.

The next day, I told the nurse I'd rather they wheeled me into the janitor's closet than stay in that room another second. The janitor turned out to be a very nice guy and not a bad pinochle player.

After five days, they pulled out the tube and let me go home. On the way out, they wheeled me by that obnoxious lady's room. She was, of course, gone, but will live on forever in my nightmares.

I think she gave me post-traumatic stress syndrome. I wonder if my health insurance will cover that. It's worth a phone call.