Still, in a year when movies didn't reach their potential, it seems particularly shameful that Wendy and Lucy didn't get a Best Picture nomination. Maybe it wasn't the best picture of the year, but it was certainly of a higher caliber than some of the picks, and it showed far more inventiveness and experimentation than any of the nominees.

But films with budgets as small as Wendy and Lucy's don't get picked for big awards, and they don't get much distribution. Nonetheless, snotty film critics put it on their "Best of the Year" lists as if to say, "Up yours, America; we saw a movie that you didn't." But now you can.

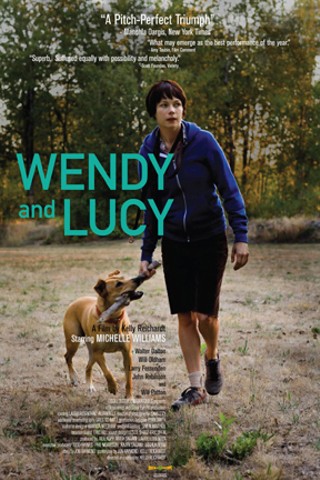

It's opening this week in Tucson in the hopes of adding to its whopping $56,000 box-office take. Michelle Williams stars as Wendy, a young woman driving across America to get to a summer job in Alaska. With her is Lucy, who is probably a dog, and is at least played by a dog.

Wendy and Lucy stop in a small town in Oregon to do some shoplifting, and then 80 minutes of very pretty, very slow-paced cinema ensue. Mostly, the story involves Wendy roaming the streets looking for Lucy, who gets lost or stolen or dognapped.

All by itself, "girl loses dog" is not a great movie plot, although it might be good advice for Rihanna. But what makes Wendy and Lucy work is writer/director Kelly Reichardt's intense sense of reserve and danger.

The opening scene involves Wendy walking Lucy through the woods as she hums the film's theme song. That alone would make Wendy and Lucy a great film in my book: There's no soundtrack, just Williams' occasional humming. The problem with soundtracks is that they accentuate the unnaturalness of film so that, for me at least, every time the music sweeps up, I'm taken out of the experience and reminded that I'm sitting in a theater seat that hundreds of unwashed asses have already sat upon.

But music that's produced organically within a scene doesn't have that problem, so Reichardt simply has Williams hum the theme song repeatedly throughout the film, and then, finally, the fully arranged and recorded version (by Will Oldham, who also appears in the film) comes on during the final credits, at which point it seems opportune to remind the audience that they're sitting in a pool of dried popcorn vomit.

Music is only one of W&L's charms, though. That opening forest sequence features a strangely terrifying moment when Lucy can't be found. Wendy calls out and eventually sees her dog snuffling around a group of crusty young hippie-punks who've made an enormous campfire. Their attitude is so much louder and more aggressive than Wendy's that they instantly seem threatening, even as they give friendly advice and scratch Lucy's ears.

This mood is helped immeasurably (actually, it can be measured; I just like the word "immeasurably") by the length of the shots. Instead of using the frenetic type of editing that's caused all of us to acquire attention-deficit disorder, Reichardt slows things way down. Wendy opens the hood of her car and looks at the engine, and the shot lingers for a few seconds. Wendy sits in the dark, and the scene remains almost completely dark and silent for a few moments. Wendy is sleeping in her car, and a camera records her as teen boys walk by, notice her sleeping there, pause threateningly and move on.

And none of this is boring, even without a soundtrack, because Reichardt so carefully composes her shots, and creates such a subtle sense of tension, that it's kind of like staring at one of those Seurat paintings that occasionally transform into killer robots and go on bloody, pointillist rampages. It's pretty, and captivating, but you feel a little unsafe.

None of this would work if the actors couldn't pull off an extreme naturalism, and most of them do. Williams could actually be the disaffected 20-something she plays, and the woodland crusties are freakishly authentic. Best of all is Wally Dalton as a friendly, white-haired, pony-tailed security guard who charmingly slips Wendy $6 to help her out. There's something so sad and kind and pathetic about the $6, and Dalton plays all of his scenes as though he's accidentally wandered onto the set and doesn't realize that this is a movie. Will Patton, who's always good, is also in Wendy and Lucy, but he's so professional that he's almost out of place. Still, he's fun to watch.

With Wendy and Lucy, Reichardt has captured a degree of intimacy that's rare in modern American filmmaking. Her patience and faith in the audience really pay off, and if you want to see what cinema can be when the emphasis is on composition, character and mood rather than sound, fury and technology, you'll find Wendy and Lucy well worth checking out.