A friendly Border Patrol agent, who has just lit up a cigar, is pointing across the international boundary to Nogales, Sonora. He says that these are the places where "lookouts" are watching him and other agents of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. I look through the bollard-style border fence, reinforced steel poles placed side by side, and squint to see the multitude of buildings and houses on the Mexican side, many crowding to the border fence. I don't see the people that the agent is referring to.

"Wherever we move they know," the agent, dressed in the typical forest-green uniform, says pointing at his eye. "If we move to another place, they will know."

I look, but all I can hear is the sound of children's voices. Below us there is a flurry of laughter and music coming from what sounds like a school festival. It is no more than 100 feet away, but in Mexico. When I look down the 25-foot embankment trying to spot the school, I can see the cross and flowers—a shrine dedicated to Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez—at the corner of two busy streets. This was the place where a Border Patrol agent, or agents (the case remains unresolved), shot onto the Mexican street where the 16-year-old Elena Rodriguez walked, hitting him 10 times with bullets on Oct. 10, 2012. A police report claims that the agents were responding to people throwing rocks. The expensive cameras that stare down from the yellow post above us apparently captured what happened, but still no video has been released.

"I hope the smoke isn't bothering you," the agent says, noticing that the wind on this overcast, blustery day is blowing the cigar smoke around. Of course I'm curious to know why he is smoking a blunt, midshift, but I don't ask.

As he continues to point out the "bad guys," I follow the path of the border wall with my eyes. It snakes up and down the hills for miles in Nogales. Just down the hill from us are two tires connected to a tree with a yellow rope that sways in the wind. The most massive and expensive border enforcement apparatus in the history of the United States had been built right through this makeshift playground on the U.S. side, and right through where the voices of the kids at the school fiesta in Mexico can be heard.

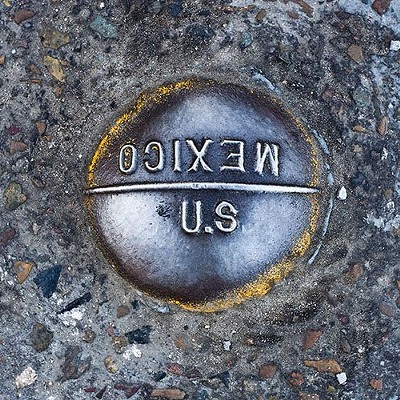

People don't call this Ambos Nogales (referring to both Nogales, Ariz., and Nogales, Sonora) for no reason. They call it that for the numerous familial, community, social and economic ties that crisscross the border like the Cinco de Mayo parade that went from Mexico to the United States as recently as the 1980s. Now, the wall is just the beginning of the divisions. If you are a kid growing up in Ambos Nogales you could be the enemy, you could be the ally or you could be both at the same time.

Creating the Fertile Ground

When kids are bored in Nogales, Ariz., they hover between two places—City Hall and Peter Piper Pizza, according to Andres Lozano. Nogales has a population of about 25,000 people—much less than in Nogales, Sonora, where the population is close to 400,000. City Hall has a park, and in the back of the building is an area for events such as small carnivals where businesses and city agencies have booths. During such events, the Border Patrol is almost always there, Lozano tells me.

Long gone are the days in the 1970s when Lozano's father, like many others, crossed the border from Mexico through a hole in the chain-link fence to play basketball or to pay a bill at the local department store. An operation in the mid-1990s, known as Operation Safeguard, put an end to those types of crossings. More agents, more technology and a towering wall built from repurposed military landing mats—which would later be covered with some spectacular Mexican-side graffiti—were part of an operation that would transform the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. Ambos Nogales would never look the same again.

When Lozano was growing up in Nogales during the post-Sept. 11 era, more and more money and resources poured into border enforcement, especially with the new national security mandate. Keeping terrorists and weapons of mass destruction out of the U.S. became the priority mission of the Border Patrol. According to an Associated Press investigative report, approximately $90 billion went to border policing between 2001 and 2011. Some of the money went toward beefing up the Nogales Border Patrol station. It now has 720 agents, 500 vehicles and firearms such as M4 rifles, shotguns and compressed-air-powered guns, in addition to standard-issue pistols carried by all agents.

Lozano says that in the mid-2000s he and a group of his friends were at City Hall when they walked past the Border Patrol booth. A uniformed Border Patrol agent rushed out, stood in their path, and said, "Hey you guys seem young, you seem athletic. Why don't you sign up for the Explorers?"

There are a number of different youth groups in Nogales, Lozano explains, but two of them always seem to put pressure on everyone else. One is a group of kids who are "very religious, and they go to religious meetings over the weekend and they'd try to get you to go to the weekend meetings."

The other group that "sticks out to me," he says, is the group of kids "involved with the Explorers."

The Explorers program was how, as Customs and Border Protection spokeswoman Stephanie Malin explained to me in a 2011 email, "the youth of America" were connecting with "the largest federal law enforcement agency in the country." What's more, she wrote, the "Explorer program is a great opportunity to instill the same values and commitment CBP employees bring to the job every day." In Nogales, Post No. 125 is composed of boys and girls between 14 and 20 years old who meet on a regular basis.

According to the CBP website, Explorers are "trained in numerous law enforcement scenarios that are based on actual training received by CBP officers and agents." To bolster endurance, they train by doing pushups and situps. They are expected to be able to run 1.5 miles in less than 15 minutes. There are a number of role-play scenarios in which they use their "red guns," fake red-colored handguns and assault rifles. One agent told me that the guns were for training that prepares Border Patrol Explorers for pursuing "intruders" in the desert, raiding marijuana fields and responding to hostage-taking situations. They learn how to take people down and handcuff them. The Explorers learn about borders, citizenship, CBP history and even a bit of immigration law.

But Lozano, like many youths in many border towns, didn't like the Border Patrol. He and his friends spent his childhood playing "hide-and-seek" with agents. They would chuck rocks towards agents' vehicles and run with adrenaline pumping when the "men in green" pursued them in response.

A few weeks before agents tried to recruit Lozano and his friends at City Hall, another Border Patrol agent had pulled a gun on Lozano after he climbed a slow-moving train to get across the train tracks. There is no overpass in Nogales, so when the train rolls through, it cuts the town in half and there is no way to get to the other side until all the railcars chug through.

Lozano was on the way to his best friend's house, on the other side of the train tracks. He was not crossing an international border. After a Border Patrol agent in a patrol vehicle saw Lozano climb down from the train, he peeled out, drove over a curb and came to a screeching stop. He then pulled out his gun and yelled, "Freeze!"

Lozano stopped and tried to get his identification out of his pocket, and the agent yelled at him to get his hand out of his pocket.

The agent came over, pulled Lozano's wallet out, looked at his ID and then, according to Lozano, slammed it on his chest and told him that the train was federal property. Lozano was 15 years old at time.

The incident was still fresh in his mind a few weeks later when the Border Patrol recruiter tries to entice him to the information booth.

"I'm not interested," Lozano says he told him. "Go away."

"Fine, whatever. Blow me off. You think you're cool. Do whatever you want. See that Corvette?" the agent responded, according to Lozano. There was a yellow Corvette parked in front of the park.

"What about it?" Lozano asked.

"It belongs to my boss," the agent said. "My boss, who has only been in the Border Patrol for two years more than me, is driving around in that badass car. Wouldn't you like to be driving around in that car?"

Although young children might think it was cool, which Lozano admits he did briefly himself, "It just hits you weird," he says. "It seems funny to wave the little toy in front of a little kid and say check out that Corvette, it could be yours if you chase around your own people."

In a place like Nogales, where job opportunities beyond minimum wage are difficult to come by, such words carry weight. Every kid anywhere near the border knows that in a Border Patrol agent's first year, the agent can earn more than twice as much as what a high school teacher makes.

CBP Post 125 in Nogales is one of many CBP Explorer posts. There are more in San Diego; El Paso, Texas; Miami; and San Juan, Puerto Rico. They are also in Tampa, Fla.; Chicago; and Anchorage, Alaska. They are in Maine and Montana and New Jersey. The stated purpose of the program is for teenagers to explore potential career opportunities in law enforcement. This particular Boy Scouts of America Learning for Life program, however, changed drastically after 2001. "Before it was more about basics," Border Patrol agent Johnny Longoria told The New York Times, "but now our emphasis is on terrorism, illegal entry, drugs and human smuggling."

Indeed, it is a persuasive message, creating fertile ground among youth so that the border-policing mission can advance well into the future. "I want to be a Border Patrol agent," 14-year-old Miguel Martinez (not his real name) tells me in his house in Nogales. Martinez comes to the door dressed in the camouflage uniform of the Civil Air Patrol, a U.S. Air Force auxiliary. He is in its youth program, the equivalent of the Explorers. While not part of the Border Patrol, the Civil Air Patrol carries out surveillance missions over the borderlands. Throughout our interview, Martinez insists that he doesn't want to work in an office, that he wants an "active" job. He loves to fly, he says. He also likes horses and ATVs, two more reasons he wants to become a Border Patrol agent.

Yet Martinez still crosses the border into Mexico regularly to visit family and do basic things like get a haircut. His brother Lenny, who also wants to be a Border Patrol agent, says that he thinks the large wall that slices through the community is good. He says it keeps out the desmadre—the total fucking mess—without going into what exactly that means.

When Nogales piano teacher Gustavo Lozano asks Lenny and Miguel, both of them his students, if they would like to work for an agency that harasses and arrests fellow Mexicans, 16-year-old Lenny pauses, looks for words, and says, "Of course I don't want to arrest my own people . . . but I still like what they do."

Miguel is more defiant: "I wouldn't let that happen." He pauses. "I would sue them." You could almost see the 14-year-old's muscles tense up through his camouflage outfit.

Should I Be Afraid?

The cigar-smoking agent is from the borderlands himself—Douglas, Ariz.—and perhaps even was an Explorer. He has been in the Border Patrol for five years. Before that, he tells me, he was working in a tech company in California but there were layoffs during the recession in 2008. As he talks, the wind continues to blow in persistent gusts on this overcast day.

The agent's brother-in-law at the time was working in the Border Patrol. His brother-in-law told him there were no layoffs in the agency. It was true. The agent was hired during a massive expansion when the Border Patrol increased its ranks from 12,000 agents to its current 21,000.

"But now," he said, "we are worried about furloughs." He laughs, as if not sure whether to believe himself or not.

But the agent doesn't dwell on the potential pay cuts. He points across the border at an enemy that seem both omnipresent and vague at the same time. The feeling that he evokes is that the Border Patrol is vulnerable, under constant threat.

Yet never before in the history of the Border Patrol have there been so many technological gadgets of war tailored to the agents' intense surveillance mission. High-tech "war rooms" have agents staring at computers and camera monitors, attempting to detect not only drug runners and undocumented border-crossers, but also national security breaches.

Perhaps what most typifies this transfer of battlefield technology to the border is a fleet of surveillance Predator B drones with high-powered infrared cameras that CBP now has at its disposal. One drone, manufactured by Northrop Grumman, has "man-hunting" radar developed to detect roadside bombers in Afghanistan but is now used to find border-crossers.

Douglas resident Tommy Bassett explained to me what the Border Patrol expansion has meant for borderlands residents: "First you see a couple Border Patrol agents go by. Then you start seeing Border Patrol four-wheelers. Border Patrol agents on bicycles. Then you see the Border Patrol tank. And the drones and the helicopters and the fixed-wing aircraft. Pretty soon you see the Border Patrol and other federal agents carrying M-16s. And military hardware. And laser sites. And at some point you kind of think something's wrong. You wonder: Should I be afraid?"

They Cut Off His Wings

It is an overcast January afternoon in the bustling centro of Nogales, Sonora. I am waiting for Diego Romain Elena Rodriguez to arrive. His brother Jose Antonio's shrine is approximately one block from where I sit. I am looking out the window at cops riding by in glow-yellow vests, trying to compose questions to ask a 20-year-old who lost his brother just 16 months before.

"He was my brother, but he also was my best friend," is the first thing Diego tells me after giving me a quick hug when he arrives to the restaurant.

On the evening of Oct. 10, 2012, Diego was working in a small shop a few blocks from the border, which was his brother's destination as he walked along the border wall.

Diego tells me that Jose Antonio never arrived at his store. Nor did he come home that night to the neighborhood where they lived, La Capilla, which is located in the hills rising above the city. It is a neighborhood that has witnessed radical changes in U.S. border enforcement, from chain-link fences in the early 1990s to the current massive, expensive version that includes bright stadium lights that shine into Mexico.

In La Capilla, it gets quiet quickly at night. So everybody heard the burst of shots fired from across the border. The bullets echoed through the canyons. They could see people gathering by the border, a cluster of Border Patrol and emergency vehicles, bright lights and a helicopter flying overhead. "I never imagined that it was Jose Antonio," Diego tells me.

When his brother didn't arrive home, "I searched for him the entire night." It wasn't until he read the paper the next day, that he found out that his brother was dead.

"They cut off his wings," Diego says to me across the table at the cafe.

Diego said that he was hurt so deep inside, "that I can't even explain it." He fell into a depression. He was barely attentive in school. He didn't play basketball with his friends. His mother, his grandmother and his two little sisters all felt his intense pain.

"We aren't at war," Diego says adamantly, "so why did they kill him?" Eyewitnesses say that Jose Antonio was unarmed and doing nothing more aggressive than walking by. He is one of at least 42 people killed by Border Patrol agents since 2005.

Vivid Divisions

On Jan. 31, the Mexican newspaper Excelsior ran a story that included several photographs of children with Border Patrol agents near the border wall in San Diego. In one picture you see a young blond girl with her back to the camera looking at a mannequin that is propped up in front of the border wall. It appears as though the mannequin might represent a person who had just climbed over the fence. A Border Patrol agent was hunched nearby holding a paint-ball pistol.

It is impossible to know exactly what the agent was saying to the girl in that photo. He could have been explaining the technicalities of the pistol. The mannequin, perhaps, as CBP said in response to allegations reported in Excelsior, wasn't meant to be an "attacking migrant." Maybe it was just to, as CBP explained, "bring members of the community together to build relationships and increase awareness about law enforcement."

Or, perhaps, like the agent with the cigar, he was explaining the perpetual enemies the Border Patrol faces. Perhaps the agent was telling the girl that people are divided between the good and bad, legal and illegal, the innocent "us" and the terrorist "them." And which side you fall on is, as Andres Lozano and Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez's vastly different experiences show us, is in many ways an accident of birth.