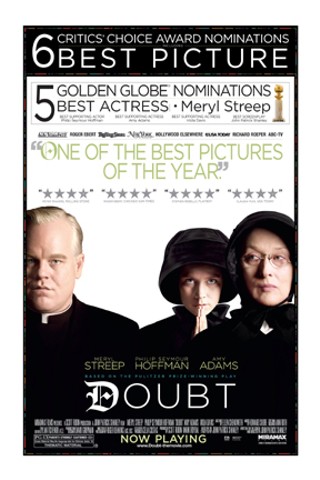

I mention this, because the writer/director of Joe Versus the Volcano is John Patrick Shanley, who's also the writer/director of Doubt. Which is kind of like being the author of Encyclopedia Brown and the Case of the Slippery Salamander and then going on to write Ulysses. Which is to say that while Joe Versus the Volcano is perhaps underrated, Doubt is one of the best-written films of the last, oh, I don't know, pick a number, let's say 23 years. The script is funnier than anything Judd Apatow ever farted on, sharper than the pangs of regret, and more believable than an Illinois governor getting caught in a corruption scandal.

The story is a neatly paced mystery that's rife with ambiguity. Philip Seymour Hoffman plays Father Brendan Flynn, a man who has a crazy idea that Christianity should be about love and niceness and the feeling you get when you look at a fluffy kitten nuzzling a fuzzy bunny. He's opposed by Sister Aloysius Beauvier (Meryl Streep), the hard-nosed Catholic school principal who believes transistor radios and ballpoint pens are leading America into a moral wasteland.

These character types, and the film's ad campaign, would indicate that the film is about the conflict between someone who would spread joy and love, and someone who would cold-heartedly enforce all rules. But it's totally not that movie. Instead, it delicately balances several themes and makes no one out to be a hero or a villain.

Sister Aloysius has come to believe that Father Flynn is behaving inappropriately toward a 12-year-old boy. Her evidence is thin, but not completely unconvincing. Complicating matters, the boy is the only African-American student at the school. (The year is 1964.) Further complicating the matter, the boy is oriented somewhat differently than the midcentury sexual norm. Adding even more complexity, in the Catholic church of that era, men held all the power (as opposed to the gender-neutral paradise we have in the contemporary Catholic church), and Sister Aloysius must fight against an institutional disregard for women in order to stop what she believes is a case of sexual abuse.

A lot of the story focuses on Sister Aloysius' efforts to exert some kind of control in a world where she is officially and doctrinally considered a second-class citizen. Shanley does a great job of bringing this across: A scene of the nuns having dinner is silent and glum, their food unappetizing, glasses of milk sitting beside their plates. The priests are then shown eating a great, bloody roast beef while they laugh, smoke and drink beer and scotch.

These scenes are part of Shanley's great sense of place. The school is all chipped wood and dull colors; the desks are scratched and dingy; the floors seem to be made out of linoleum and despair. It's surprising that Shanley has such visual skills, this being only his second directorial effort, but he's well-aided by cameraman and cinematographer Roger Deakins (No Country for Old Men, Fargo, The Shawshank Redemption). Deakins introduces sneaky touches, like tilting the camera during indoor shots so that the lines of the walls and ceilings acquire a disorienting skew.

But in spite of Deakins' skill, the best part of this film is not its visual sensibility; it's the scripting. Imagine you've been watching a comedy, the funniest you've seen, and then suddenly, you burst into tears, because what you've been laughing at involves the abuse of a child. And yet, you're not angry about the presentation: It is the most respectful film about the topic you've seen. And then you realize that this is because, in each line of dialogue, the characters expressed a kind of complexity that's almost forbidden in film. It's not that they're wavering between good and evil, or that the bad things they do are done in the name of good, or some such action-movie conceit. It's that none of the characters actually know if they're good or evil. They are, in short, full of doubt. And that is an emotion that is rarely shared with an audience.

Of course, Shanley has some serious help from the cast. Hoffman keeps it understated until necessary, and then pours on a painful mix of feelings. But the biggest surprise is Streep: I think she's probably the most overrated actor in the history of film. She spent her first 20 years or so perfecting a single expression, a blank look aimed at an unfocused horizon. But of late, she's started to deserve the praise she's always received. She still seems stiff and artificial, but in Doubt, that works for her, and she's actually able to show some depth and complexity beneath her nunnish exterior.

Her final sequence is devastating, easily the best work of her career. That she has an amazing script to work with doesn't fully account for the power of her performance; her interpretation is insightful, and her skill is stunning. Assisting throughout is Amy Adams, who plays the naïf with a little too much gusto. But if she's a bit broad, she's there mostly to support Streep and Hoffman, and she certainly doesn't get in their way.

In sum, Doubt is a near-perfect attempt at creating that rare cinematic creature, a film that doesn't tell you what happened, nor what to think about it, but nonetheless satisfies all the requirements of good storytelling.