Monday, March 7, 2022

RED ROCK – All around Picacho Peak, the Sonoran Desert is brown and dry and rough. The soles of your feet could not tell the desert hardpan from an asphalt road.

About 2,500 feet above the ground, water vapor streaming northeast into Arizona from the Gulf of California condenses into larger and larger droplets until they’re too heavy to remain suspended. When thousands become one, that drop falls toward earth. For two to seven minutes, the drop freefalls, reaching speeds up to 20 mph before it strikes the surface.

The impact is quiet. But for the compacted soil, the rain does not provide necessary moisture, it tears the land apart. The crust on top of the soil keeps the water from penetrating. As the water seeks its level, it rips across the surface in muddy flash floods, further eroding topsoil.

On an 8-acre plot off South Aguirre Lane in unincorporated Red Rock, Ricardo Aguirre is using his family’s old ranch to prove there is a way to stop the flooding and erosion. He can’t make the rain fall, but his mission is to prepare the land to utilize the rain when it comes, “making sure every raindrop is effective the moment it falls on the ground,” said Aguirre, a drainage engineer.

“Which means get it in the ground and make sure that it doesn’t run laterally across.”

Aguirre directs land management and water security for the civil engineering firm WEST Consultants Inc., which specializes in water resource management and has offices in Arizona, California, Oregon, Washington and Texas. The land where his family once farmed cotton and ran cattle is where he now demonstrates methods to restore grasslands, improve soil health and ultimately reverse desertification.

Deserts cover more than 41% of Earth’s landmass, according to the United Nations. But because of human activity, deserts are growing by about 33,000 square miles – the size of Ireland – every year.

Deforestation, destructive agricultural practices and climate change have contributed to the degradation of topsoil and expanding deserts. Yet healthy topsoil is essential to growing food, and according to one U.N. study, if land degradation continues, topsoil could be gone within 60 years.

The symptom of desertification that Aguirre is addressing is excess flooding. He’s looking at alternative land management practices to return water cycles to nature’s designs.

Going against the grain

Aguirre spent more than a decade of his civil engineering career utilizing modern methods of stormwater management. His textbooks and his degree from University of Illinois taught him to manage water with a pipe, a channel and a hole in the ground. He described his career as “intrinsically connected to the land,” and that connection, along with his agrarian roots, led to much deliberation in the back of his mind. He felt a responsibility to leave the land he worked with better than he found it.

In August 2010, he became a father, and those deliberations moved to the front of his mind.

Aguirre imagined a conversation 15 years in the future in which his son asks whether he took advantage of being in a position to do something about the degrading environment.

“Looking at the designs that I had, that are now constructed, and the impact that they have on the environment,” Aguirre said, “I didn’t like the answers that I was giving … for that conversation with my son.”

Aguirre relegated his textbook knowledge and looked to a different teacher: Mother Nature. He studied how nature configured the water cycle, and how humans used to exist in and be part of the mineral cycles, eating and drinking off the land and returning the nutrients as wild animals do today, before the industrial revolution began in the 1700s.

“So through that discovery, I realized that we are going 180 degrees against the grain,” Aguirre said. “And the harder that we fight nature’s principles, the more degradation that we’re creating.”

In his research, Aguirre discovered holistic land management, which uses controlled grazing techniques to work cooperatively with ecosystem processes. It was pioneered by Allan Savory, founder of the Savory Institute, who grew up in South Africa loving the environment and despising livestock because he believed grazing damaged the land.

As a young biologist in Africa, he worked to set aside land to become national parks. In the 1950s, the protected land he studied in Zimbabwe continued to deteriorate, and he concluded there were too many elephants for the land to sustain. His superiors confirmed his research.

“Over the following years, we shot and killed 40,000 elephants to try to stop the damage,” Savory said in a 2013 TED Talk. “And it got worse, not better.”

He described it as “the saddest, and biggest blunder” of his life.

Savory was determined to find solutions. He traveled to the western U.S., where cattle had been removed from land to demonstrate how that would stop desertification. But he said he found the opposite.

Savory came to understand that the vegetation being lost in these expanding deserts was developed over thousands of years and adapted to large herds of grazing animals migrating across the landscape.

Aguirre is trying to address these same issues in the Southwest, explaining that land degradation has been caused by the lack of migratory animals brought on by urban expansion that reduces and limits animal populations.

When a fence goes up, said Grant Tims, Aguirre’s ranch manager, the land is left idle.

“So in arid climates, it’s the rest that is the problem,” Aguirre said, as Savory witnessed in Africa. “Where most people think it’s overgrazing.”

Aguirre relates “the health of the land to the health of the human body,” comparing land degradation to muscle atrophy in people: A sedentary lifestyle will cause the body to deteriorate.

“You’re not stressing the land with hoof action, you’re not stressing the land with animal impact,” he said. “That stress will actually cause a positive response.”

Aguirre reached out to the Savory Institute after the 2013 TED talk with a new concept of connecting civil engineering and holistic land management. In 2014, he went to Zimbabwe to see Savory’s work for himself.

Aguirre visited a small stream with big implications. The stream in recent decades had been ephemeral, meaning it only runs after rains, but villagers in the area had transformed the stream through holistic land management.

“For me, as a drainage engineer,” Aguirre said, “that just blew my mind that seven out of nine villagers that subscribed to this program were able to restore the watershed function to the degree that the streams were running again, on a perennial level, and reversed 40 years of an ephemeral stream.”

Shortly after, Aguirre became the director of his own Savory Hub in Arizona, which now is called the Drylands Alliance for Addressing Water Needs, where he teaches holistic land management practices. His goal is to transform his desertifying homeland, halfway between Phoenix and Tucson.

“That’s … my personal BHAG (big hairy audacious goal) as a drainage engineer is to get that level of watershed function back into the watersheds of Arizona and the Southwest and beyond,” he said.

Aguirre took the idea of using land management instead of concrete and steel to address water resources to WEST Consultants, which welcomed the idea.

How a watershed works

A watershed is an area of land that “channels rainfall and snowmelt to creeks, rivers and lakes” according to the National Ocean Service.

“If you look at a leaf,” Aguirre said, “a leaf pattern shows that. Because that’s how nature has figured out how to get nutrients.” Or like the human body, he added, with a system of veins leading to the heart.

Ideally, most rain will seep into the soil, recharging the aquifers and moving through the soil toward a common body of water.

When raindrops fall onto land where watershed function is deteriorating because of desertification, it runs off.

“It begins to make one, two, three, four one-off tributary streams,” Aguirre said. Those ephemeral streams lead to extensive erosion, which destroys roads and bridges as well as topsoil.

“A functioning watershed should really only have one, maybe two tributaries,” he said.

The remedy, Aguirre believes, is to restore vegetation and root systems to the barren soil.

Erinanne Saffell, Arizona’s state climatologist, described the important role of plants in the hydrologic cycle.

“We want to have what’s called interception,” she said, “which is where the precipitation will hit trees, vegetation of some kind … that allows the water to infiltrate more readily and recharge our aquifers.”

Vegetation acts as “storage locations and transfer mechanisms of water,” Saffel said. “If (raindrops) come down and hit bare soil, that’s actually very disruptive to having water go into the ground and recharge our aquifers.”

Water security concerns continue to loom in Arizona, where heavy monsoon rains in 2021 did little to alleviate long-term drought conditions, according to the Arizona Department of Water Resources. Arizona is still experiencing severe drought or worse this year.

Aguirre is preparing the land on his demonstration site to better receive rain to revitalize the grasslands, which are now bare, but under the soil lie seeds hungry for water.

“What we can expect is that there is a seed bank, roughly about 2,000 seeds waiting to be germinated in every square yard,” Aguirre said. “It’s just a matter of assembling the right conditions for that germination.”

Soil intervention

Like a human body that has spent years resting, failing to get proper nutrition and not drinking enough water, the desert needs help, Aguirre said.

The health services Aguirre and Tims provide are moving sheep, goats and chickens across the demonstration site; their hooves break up the hard soil and their dung and urine fertilize it for weeks at a time.

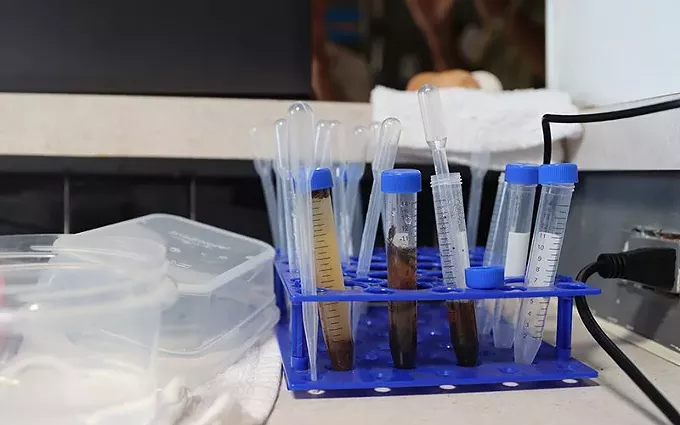

To accelerate the regeneration process, Aguirre and Tims also use what they call biological soil amendments, made up of bacteria, fungi and other microbes. The increase in this carbon-based matter helps provide nutrients to plants and boost the soil’s ability to absorb and hold water.

When Aguirre returned to the property he grew up on in the summer of 2019, “we started with basically bare soil,” he said. Now, especially after heavy monsoon storms in 2021, there is growing evidence that the land is responding positively to the animals, in some places the evidence is as tall as him.

“The grasses where the animals have been have been beyond waist high, compared to where the animals have not been, are barely coming up to a person’s knees,” Aguirre said.

On a tour last fall of the site, Tims lifted a blue tarp off a compost pile used to brew the biological soil amendments. Unlike the surrounding landscape, the little world under the blue tarp is teeming with life that flies, jumps or scurries away as the tarp is removed.

Aguirre and Tims steep the compost like a tea bag, extracting the abundance of microbial life.

“We take that water and put it in a brewer, and that’s what we’re actually putting into the soil,” Tims said. Using a low impact plow with circular blades, the brew soaks into soil, priming the pump for seed germination.

The lungs of the land

Revitalizing grasslands in desertified regions does more than improve watershed function, it allows the soil to breathe in and trap carbon – making it a natural countermeasure to the rising carbon dioxide levels contributing to climate change, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Healthy vegetation sequesters carbon through photosynthesis, pumping it down through its roots and into the soil. The healthier the soil, the deeper the carbon may go.

Pawlock Dass, with the department of land, air and water resources at the University of California, Davis, co-authored a 2018 study that shows grasslands are an even more reliable carbon sink than trees, particularly because of the increasing threat of wildfire.

Dass said healthy forests store more carbon than grasslands, but there’s a catch in California, Arizona and other arid places.

“Forests store a large percentage of their carbon above ground, that is the bulk of the tree biomass, that is a trunk of a tree,” Dass said, and in a wildfire, all that carbon is released into the atmosphere.

Grasslands, however, store most of their carbon below ground as root biomass, he said, where it’s protected from fires and promotes healthy soil that allows grasslands to grow back.

Dass’ study looked specifically at companies investing in planting forests to offset carbon emissions.

“If that carbon gets emitted back into the atmosphere (in a fire), it doesn’t really make much sense,” Dass said. “All the investment is basically lost.”

Restoring the cycle

When a raindrop strikes areas of revitalized grass off South Aguirre Lane, it doesn’t tear the land apart. It gets captured by the vegetation and transferred into the soil. The root systems and growing microbial populations absorb and hold the water – promoting more grass growth and more water capture. Eventually, it seeps down to recharge the aquifers.

“We can’t make it rain, but what we can do is we can make the rainfall more effective,” Aguirre said. “We’re offering land management as an alternative to engineering.”

The process starts in the lab, where Aguirre and Tims inspect the bacterial and fungal population of the compost through a microscope. The microbiology helps germinate the seeds in the soil, the grass then is grazed by chickens, sheep and cows that further break up the soil. More water is absorbed, which means more grass, more animals, more life.

The objective is to counteract desertification and its symptoms.

“All of (the problems) come back to this,” Tims said. “Compaction and biology.”

It turns deserted land into a valuable, fertile asset. It restores watershed function, helping with water security concerns, according to Aguirre and Tims.

Don Steuter, with the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon Chapter, which has been critical of Allan Savory’s cattle grazing claims in the past, expressed cautious optimism about Aguirre’s undertaking.

“We’re always interested in projects like this,” Steuter said, although he believes the success of cattle-grazed land is more likely to be a site-specific fix rather than a universal one.

“We’d be tickled to death if cattle could make the land better,” Steuter said. “It would solve a lot of our problems, but we don’t think it’s very likely.”

Still, Steuter said, he’s intrigued with Aguirre’s mission to heal watershed function and is looking forward to seeing the results.

Aguirre and WEST consultants are working on land restoration projects in Cochise County and are seeking state and federal contracts as well.

Aguirre said he’s the only civil engineer he knows of who’s bridging holistic land management with his profession. He hopes not for long.

“The overarching objective that I believe my calling is, is to reinvent my profession of civil engineering,” Aguirre said.

In three years, when his son turns 15, Aguirre can realize that imaginary conversation. If his son asks him if he used his position to improve the degrading environment, Aguirre no longer has to give the answer he never wanted to:

“I didn’t do anything about it.”

Wednesday, December 1, 2021

Arizona officials and advocates praised U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland for declaring “squaw” as a derogatory term and ordering that it be removed from any geographic feature on federal lands, which will rename 67 locations in Arizona.

“The removal of such language is bittersweet as it addresses an everyday indignity that Native Americans are continuously subjected to, but also highlights the deeply-rooted anti-Native sentiments that our country was founded on and for which our government is yet to atone,” Pima County Recorder Gabriella Cázares-Kelly said.

Cázares-Kelly is a citizen of the Tohono O’odham Nation and the first Native American to hold a countywide seat in Pima County.

“Deb Haaland’s move to remove a well-known racist and derogatory term that sexualizes Indigenous women from everyday government use is incredibly powerful and long overdue,” said Cázares-Kelly.

The move comes at a time when many federal leaders are finally acknowledging the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women epidemic, Cázares-Kelly said. According to the National Institute of Justice, 84% of Indigenous women experience violence in their lifetime, compared to 71% of white women.

Haaland issued her secretarial orders on Nov. 19.

“Racist terms have no place in our vernacular or on our federal lands. Our nation’s lands and waters should be places to celebrate the outdoors and our shared cultural heritage – not to perpetuate the legacies of oppression,” Haaland said in a press release.

As part of Haaland’s order, the Board of Geographic Names – the federal body tasked with naming geographic places – will need to implement procedures that will remove the term from federal usage.

Wednesday, November 17, 2021

The following travel restrictions and road closures will be in place at 6 a.m. Saturday because of the annual El Tour de Tucson bike race.

Downtown – Sixth Avenue, north of 22nd Street and south of Broadway, will be closed to motorists from 3 a.m. to 5 p.m., after the last rider. Expect additional downtown side street closures.

East side – Houghton Road will be closed to motorists from Mary Ann Cleveland Way/Old Vail Road to Sahuarita Road from 6 a.m. to 3 p.m.

West side:

- Silverbell Road southbound from Ina Road to Goret Road

- Mission Road eastbound ramp onto Starr Pass Boulevard

- Aviation Parkway eastbound from Broadway to Golf Links Road

- Wilmot Road southbound from Golf Links Road to Davis Monthan

- Nicaragua Drive/Calle Polar/Escalante Road eastbound from Wilmot Road to Kolb Road

Additional closures include:

- I-10 and Houghton Road exits

- Kolb Road southbound from Escalante Road to Valencia Ramp Road

- Valencia Road eastbound from Kolb Road to Old Vail Road

- Mary Ann Cleveland Way westbound from Colossal Cave Road to Houghton Road

- Irvington Road eastbound from Kolb Road to Houghton Road

- Houghton Road northbound from Irvington Road to Escalante Road

- Escalante Road eastbound from Houghton Road to Old Spanish Trail will be highly restricted to travel

Further information about El Tour de Tucson, including a route map, can be found at eltourdetucson.org/el-tour-de-tucson/route/.

Motorists may experience lengthy traffic delays associated with this event, so please plan accordingly. The traveling public should use caution when driving, bicycling or walking in these areas. Please watch for event participants, obey all traffic control, and watch for detour signs and personnel providing traffic control.

Tuesday, November 2, 2021

PHOENIX – A 90-day public comment process has begun on a proposal to allow more endangered Mexican wolves to be released into the wilds of Arizona and New Mexico, where, federal officials say, the animals are thriving.

“Recovering the Mexican wolf remains a top priority for the service, and we continue to make steady progress toward this goal,” Amy Lueders, the Southwest regional director for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said at a news briefing Wednesday.

At least 186 Mexican wolves live in western New Mexico and eastern Arizona, according to a 2021 study. The wolves – a rare subspecies of the gray wolf – were all but wiped out by the 1970s before being listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Efforts to reintroduce them to the region began in 1998.

“The wild population of Mexican wolves in the United States saw its fifth consecutive year of growth in 2020,” Lueders said.

To keep the population growing, Fish and Wildlife wants to remove the population limit, which is set at 325. It also wants to increase the number of wolf pups that are bred in captivity and released into dens to help improve the genetic diversity of the growing population. The service also wants to temporarily restrict what is considered an allowable “take,” meaning to kill or capture a wolf threatening livestock or human lives.

Proposed changes follow a 2018 court order for the service to revise the designation of the Mexican Wolf Reintroduction Project to make sure the experimental population contributes to long-term recovery of the wolf.

Wednesday, October 13, 2021

WASHINGTON – Arizona projects got $110 million last year and will get another $159 million in the fiscal year that started this month, or more than 9% of all funding nationally under the Great American Outdoors Act for those two years.

The money, dedicated largely to national parks but also to federal lands and tribal schools, has been welcomed by tourism and environmental groups, who said it is long overdue.

“The National Park Service has been underfunded over the years,” said Kevin Dahl, senior program manager for Arizona in the National Parks Conservation Association’s Southwest region.

“These are our jewels, and with visitation and with normal wear and tear, there’s a lot of buildings, a lot of roads, trails, etc. and those all need regular maintenance,” he said. “When you don’t maintain them over time, the backlog of maintenance becomes pretty high.”

For national parks, the backlog of deferred maintenance totaled $11.9 billion in 2018, according to data from the National Park Service. More than $507.4 million of that was for projects in Arizona, with $313.8 million needed in the Grand Canyon National Park alone.

Joe Galli, senior adviser in public policy at the Greater Flagstaff Chamber of Commerce, said the funding is critical to not just the park, but the region.

“It’s very good for improving facilities and maintenance, and enhancing the visitors’ experience, those things are critical to the lifeblood of visitation in Arizona which is a critical component of our economy,” he said.

Monday, October 11, 2021

Thursday, September 30, 2021

Visitors to Saguaro National Park West will see scenic roads closed from Oct. 4-30 for construction.

Access to Bajada Loop Drive from the Hugh Norris Trail Head to Golden Gate Road will be closed from Oct. 4-15.

After those improvements, the Bajada Loop and its amenities, such as the Sus Picnic Area, Hugh Norris Trailhead, Valley View Overlook Trail, Bajada Wash Trail and all of Golden Gate Road (Signal Hill, Ez-Kim-In-Zin, Sendero Esperanza) will be closed from Oct. 16-30.

“This will help ensure the safety of the crew working on the one-lane road, as well as any visitor who may not be aware of the closure notice,” Saguaro’s Facility Manager Richard Goepfrich said.

All traffic to these locations will be prohibited, including pedestrians and cyclists. Park officials said heavy machinery in these areas will be dangerous for all traffic. Large construction vehicles will need to use the entire one-lane road for easy transportation.

Visit nps.gov/sagu/planyourvisit/conditions for updates on construction.

Thursday, September 23, 2021

El Tour de Tucson will hold the fifth Pima County El Tour Loop de Loop on Saturday, Sept. 25, and will conclude with an after-party.

The activity, which helps promote the more than 20 nonprofit partners involved in the El Tour event, is the official kickoff for the Banner – University Medicine 38th El Tour de Tucson on Nov. 20.

The Loop de Loop is for 6:30 to 10:30 a.m. and will be held on The Chuck Huckelberry Loop. The after-party will be from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. at the Mercado Annex on The Loop, 267 Avendida del Convento, with live music, prize drawings and more.

The band Badlands will play from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Raffle tickets will be provided at the event.

The grand raffle prize for this year’s Loop de Loop is a LeMond Prolog carbon fiber ebike, designed by Greg LeMond and retails for $4,500.

It is a free, easy, casual and fun ride open to individuals of all ages and abilities.

Wednesday, September 8, 2021

WASHINGTON – Federal regulators on Friday rejected a mining company’s request to reduce critical habitat for endangered jaguars in the Santa Rita Mountains on land that overlaps the footprint of the proposed Rosemont Copper Mine.

The decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the latest setback for Hudbay Minerals Inc., which has been working for more than a decade to get permission to open the mine that it says could create thousands of jobs and bring billions in economic development to the region.

But opponents welcomed the decision, saying the mine threatens not just the jaguar but the area’s drinking water supply.

“The people of Tucson have shown very clearly that they value jaguars and their water security more than they value this foreign company coming in here to put an open-pit copper mine in our mountains,” said Randy Serraglio, the Southwest conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity.

In an emailed statement Friday, a Hudbay representative said the Canadian-based mining company is reviewing the Fish and Wildlife decision, but that it “remains committed to the development of the Rosemont Project.”

Hudbay claims that the mine would lead to the creation of 500 jobs directly related to the project and another 2,700 indirectly related, spinning off $48 million a year in state and local taxes and generating $1.4 billion a year in economic activity for the region.

The company also claims on its website that the proposed Rosemont mine has been the subject of more than 1,000 studies by 17 federal, state and local agencies over 11 years, and insists it will operate an “unprecedented environmental mitigation program” at the site.

Tuesday, August 31, 2021

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

This story was originally published by ProPublica and the New York Times.

On a 110-degree day several years ago, surrounded by piles of sand and rock in the desert outside of Las Vegas, I stepped into a yellow cage large enough to fit three standing adults and was lowered 600 feet through a black hole into the ground. There, at the bottom, amid pooling water and dripping rock, was an enormous machine driving a cone-shaped drill bit into the earth. The machine was carving a cavernous, 3-mile tunnel beneath the bottom of the nation’s largest freshwater reservoir, Lake Mead.

Lake Mead, a reservoir formed by the construction of the Hoover Dam in the 1930s, is one of the most important pieces of infrastructure on the Colorado River, supplying fresh water to Nevada, California, Arizona and Mexico. The reservoir hasn’t been full since 1983. In 2000, it began a steady decline caused by epochal drought. On my visit in 2015, the lake was just about 40% full. A chalky ring on the surrounding cliffs marked where the waterline once reached, like the residue on an empty bathtub. The tunnel far below represented Nevada’s latest salvo in a simmering water war: the construction of a $1.4 billion drainage hole to ensure that if the lake ever ran dry, Las Vegas could get the very last drop.

For years, experts in the American West have predicted that, unless the steady overuse of water was brought under control, the Colorado River would no longer be able to support all of the 40 million people who depend on it. Over the past two decades, Western states took incremental steps to save water, signed agreements to share what was left and then, like Las Vegas, did what they could to protect themselves. But they believed the tipping point was still a long way off.

Like the record-breaking heat waves and the ceaseless mega-fires, the decline of the Colorado River has been faster than expected. This year, even though rainfall and snowpack high up in the Rocky Mountains were at near-normal levels, the parched soils and plants stricken by intense heat absorbed much of the water, and inflows to Lake Powell were around one-fourth of their usual amount. The Colorado’s flow has already declined by nearly 20%, on average, from its flow throughout the 1900s, and if the current rate of warming continues, the loss could well be 50% by the end of this century.

Earlier this month, federal officials declared an emergency water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time. The shortage declaration forces reductions in water deliveries to specific states, beginning with the abrupt cutoff of nearly one-fifth of Arizona’s supply from the river, and modest cuts for Nevada and Mexico, with more negotiations and cuts to follow. But it also sounded an alarm: one of the country’s most important sources of fresh water is in peril, another victim of the accelerating climate crisis.

Americans are about to face all sorts of difficult choices about how and where to live as the climate continues to heat up. States will be forced to choose which coastlines to abandon as sea levels rise, which wildfire-prone suburbs to retreat from and which small towns cannot afford new infrastructure to protect against floods or heat. What to do in the parts of the country that are losing their essential supply of water may turn out to be the first among those choices.